February 3, 2017

Japan Writers Conference 2016 Remembered

We asked three people who attended the Japan Writers Conference, held October 27 and 28 at Tokushima University, on the island of Shikoku, to share their impressions and notes from the talks they attended. While by no means comprehensive—and we regret not including reporting on all the sessions—our three authors give us lively and diverse accounts of what they gained from the two-day event. We hope this three-in-one report will inspire your writing or other wordsmithing endeavors. More details on the 2016 program and presenters can be found at: http://www.japanwritersconference.org/

If you attended JWC 2016 and have other accounts to add to this report you are willing to share, please write them up and send them to us at SWET.

Percepto-nauts, Let Loose! (Trane DeVore)

Grab Bag of Inspiration for Writers and Latent Writers (Richard Sadowsky) (link)

A Long Soak in the Glories of Poetry and Other Moments (Avery Fischer Udagawa) (link)

Photo from left to right: Wendy Nakanishi, Holly Thompson, Avery Fischer Udagawa, David Moreton, Suzanne Kamata

Percepto-nauts, Let Loose!

Trane DeVore

Day 1

The return trip to Osaka on the Nankai Ferry, which runs between Tokushima and Wakayama, set the tone for remembrance of my experience of the 2016 Japan Writers Conference—a wonderful final few hours at dusk spent watching clouds, islands, and red buoys drift by. It provided the defining mood that reached backwards, enveloping the conference and wrapping it all up in the same way that a snow globe can encompass an entire city and give it emotional focus.

The slow pace of the ferry was the opposite of the frenetic academic schedule that prevented me from putting together a manuscript in time to apply for David Gilbey’s “Reeling and Writhing” poetry writing workshop. I had heard wonderful things about the workshop over the years and would have liked to join in. Instead, I attended Diane Hawley Nagatomo’s talk, “Writing for Academic Publication: Practical Tips for Experienced Writers.” As a professional academic myself, I was curious to see what Nagatomo’s talk would hold. It turned out to be a useful primer on the essentials of academic writing—focused on methods to improve writing clarity. Nagatomo provided a series of useful slides that placed examples side by side in such a way that the advantages of the techniques she was discussing were clearly demonstrated; for example, in a section called “Get rid of empty words,” the phrase “owing to the fact that” was set across from the phrase “because,” an irrefutable example of the benefits of simplicity. Nagatomo, who is associate professor at Ochanomizu University, also provided a list of excellent resources, some of which I plan on using in an academic writing class that I’ll be teaching next year.

I stayed in the same room for Michael Pronko’s talk, “Creating Essays and Going Indie.” Pronko discussed essay writing as a genre, the difficulties in finding publishers interested in backing collections of essays, his experiences with self-publication, and his sources of inspiration for the Japan-focused essays that he writes. Pronko’s talk was impressive for the way he linked the art of essay writing and the act of seeing, focusing on the essay as a tool for crafting larger structures of meaning out of our random perceptual experiences of daily life. This focus on the perception of the everyday is reflected in the title of his essay collection “Motions and Moments,” and his talk was one of several that left me feeling space differently than I had been before the conference.

After lunch I popped into Peter Marsh’s presentation on “Short Stories: The Art and Science of Plotting.” I’ve been working on a few short stories recently and plot is a weak point (I generally write poetry, in which I completely lose the plot, or a kind of essayistic or academic prose that usually has more structure than story). Marsh gave several examples of his preferred techniques for developing plot points, and he discussed what he considers to be the difference between successful and unsuccessful plots. The stories related to his own experiences of structuring plots were entertaining and informative, and there was time toward the end of the workshop to get together with other writers and try out a few plot generation activities. I teamed up with the poets Goro Takano and Leah Sullivan and we attempted to discover some plots. In my notebook for this session is a sketch of a story about a man who leaves bits of his soul in a carton of eggs for safe keeping before heading off on vacation. The eggs are subsequently eaten by his roommate. I don’t know if Marsh would find this to be a good plot, but I have to thank him for providing the tools that generated what must be the strangest and most original plot I’ve ever come up with.

It was a hyperspace leap from short stories to cinema when I moved from Marsh’s workshop to Sara Kate Ellis’s talk on finding inspiration in visual prompts available on YouTube. The talk, titled—“As You Were, As They Are: Accessing Memories Through Cinema or That Ad for a Thing That No Longer Exists”—focused not just on using film and television images as a source of inspiration, but equally on using these images to access memories of the selves that we were when we first encountered them. It’s bit like a media-networked version of Proust’s madeleine, though in this case the madeleine turns out be a few clips from Star Wars, Jaws, or any other major movie you can think of that served as a formative cinematic experience. Perhaps indicative of the general vintage of myself and those seated nearby, most of us chose to concentrate on the impact that the original Star Wars had on us. We compared our memories of the movie to the scenes that were available on line, and we ran through the reels of our earliest movie-going memories in an attempt to bring our primal cinematic experiences to light as primary material for writing.

Against the maximalist aesthetic of Star Wars light saber duels, explosions, and X-Wing dogfights, Philip Rowland’s “The Really Short Poem: Writing and Publishing Possibilities” stood out like a petal on a wet, black bough. Rowland presented several examples of short poems—including several from the Haiku in English collection that he co-edited—and discussed the problems involved with writing short poems, the question of what makes a successful short poem, and the different types of aesthetic effects enabled by the short poem form. Especially useful for those interested in publishing their own short poems was the list of journals and websites specifically geared toward the short form that Rowland provided at the end of his presentation. Experiencing the quiet concision of these poems, which were sometimes as soft and subtle as the feeling of a memory that won’t quite surface and sometimes flashed with the minimalist sparkle of Tinker Bell’s teeth, was a potent reminder of the forceful effectiveness of silence, subtlety, and minimalist brevity.

Similarly useful was C. E. J. Simons’s presentation about “Writing (and Selling) a Sonnet in the Twenty-First Century.” After covering the historical progression of the sonnet through various stylistic permutations, Simons presented a number of fantastic contemporary sonnets in order to demonstrate the range of possibility when working within a form that is sometimes thought to be limiting because too traditional. Simons effectively flipped this conception on its head, revealing instead the form’s potential to inspire inventiveness through the very restrictions that it imposes on the dedicated writer of sonnets. Like Rowland, Simons introduced several journals that are dedicated to publishing the more formal and traditional verse forms that are commonly assumed to lack contemporary relevance. The strength of the poems that Simons shared and the caliber of his own wonderful sonnets show that anyone who assumes that the sonnet form has somehow played itself out has got another think coming.

Day 2

While Saturday’s sessions included several having to do with prose, Sunday was a day primarily dedicated to poetry. I started out by attending Holly Thompson’s talk, “Verse Novels Crossing Borders.” Thompson presented slides featuring pages from a number of beautifully illustrated verse novels, primarily geared toward younger readers, including several wonderful pages from her own narratives about intercultural experience, including samples from The Language Inside and Falling into the Dragon’s Mouth. Aside from Vikram Seth’s novel in verse, The Golden Gate, I’ve had little experience with novels in poetry form, and even less with novels and poetry for younger readers. Thompson’s presentation made me regret this omission and got me thinking about which of the books on her list I might give to the young people in my life to inspire them with words and images. In an unwelcome development, Mariko Nagai—who was originally scheduled to present during this session as well—was unable to make it. This was especially unfortunate since the pages featured from Nagai’s book about the Japanese internment camps set up in the United States during World War II, Dust of Eden, were exceptionally moving and also sharply relevant during a historical moment when the idea of internment camps is being publicly floated again, though this time it is Muslim citizens of the U.S. who are the targets of irrational prejudice.

At 11:00 I joined James Shea’s workshop, “Mistranslation as Poetry Exercise.” Shea, who flew out from Hong Kong, where he teaches at Hong Kong Baptist University, started by presenting a brief history of poetry that has been generated through mistranslation, and then proceeded to introduce several useful techniques for doing so intentionally. He explored two of these—homophonic and logographic translations—extensively, and handed out copies of poems in Chinese (logographic) and Norwegian (homophonic) to use as raw material for their own mistranslations. David Gilbey, Leah Sullivan, and Goro Takano all presented gloriously evocative mistranslations (you can find Gilbey’s posted on his blog). I did this kind of exercise years ago in a class taught by David Bromige, but I had forgotten just how productive it can be. The first stanza of my own mistranslation of Rolf Jacobsen’s poem “Guardian Angel,” read as follows: “Yeah, sure some banker played the flugelhorn. Dug it until morning, then the Folger’s tin half brought me back to life, like some kind of laser for the blind.”

At 11:00 I joined James Shea’s workshop, “Mistranslation as Poetry Exercise.” Shea, who flew out from Hong Kong, where he teaches at Hong Kong Baptist University, started by presenting a brief history of poetry that has been generated through mistranslation, and then proceeded to introduce several useful techniques for doing so intentionally. He explored two of these—homophonic and logographic translations—extensively, and handed out copies of poems in Chinese (logographic) and Norwegian (homophonic) to use as raw material for their own mistranslations. David Gilbey, Leah Sullivan, and Goro Takano all presented gloriously evocative mistranslations (you can find Gilbey’s posted on his blog). I did this kind of exercise years ago in a class taught by David Bromige, but I had forgotten just how productive it can be. The first stanza of my own mistranslation of Rolf Jacobsen’s poem “Guardian Angel,” read as follows: “Yeah, sure some banker played the flugelhorn. Dug it until morning, then the Folger’s tin half brought me back to life, like some kind of laser for the blind.”

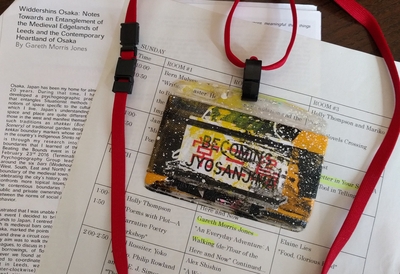

After two days of being cooped up in conference rooms, the chance to step out for a bit was welcome. What better way to do this than to go for a walk with Gareth Morris Jones? Jones, who led a walking tour of the Tokushima University Jyosanjima (the local spelling) campus called “An Everyday Adventure: A Walking (de-)Tour of the Here and Now,” focused on getting participants to reorient their perceptual fields in order to discover the aesthetic delights hidden away in the everyday spaces and places through which we commonly navigate. He began the walk by giving us plastic badges that said “Becoming Jyosanjima” to hang around our necks with straps. Now we were a team of explorers, or percepto-nauts, let loose on the campus to look at it with new eyes. Jones initiated these explorations by asking us to imagine that we were extraterrestrials, encountering the textures, lines, and marks of the campus for the first time. Instantly, a banged-up piece of plywood, painted over in several different layers, became as aesthetically appealing as a modernist painting. Jones t discussed the history of the Jyosanjima area, which was originally built up by a samurai family, and then divided us into groups to discover samurai “values” hidden in the everyday. The group of four I was part of was given the task of finding “honesty.” We eventually discovered it in the guise of a utility door covered with elegant patterns formed by the remains of ripped-away vine roots. The door had aesthetically pleasing bits of pink tape on it and several functional modifications that had been added on later (honest marks of use against the dishonest architectural purity imagined by the original designer), as well as a footprint about halfway up where someone had clearly kicked the door shut (an honest historical artifact of honest anger). We wove a story out of these marks and presented it later to the members of the session as a whole, as did all the groups. Each group had its own special encounter with overlooked spaces, including utility boxes on the backsides of buildings, secret spaces of polite privacy, and other details of the unseen campus. By the end of the two-hour session I felt like every vernacular detail in the world was ready to offer up its secrets to me.

The final session of the day was the wonderful Isobar Press reading featuring Yoko Danno, Philip Rowland, C. E. J. Simons, Holly Thompson, and Paul Rossiter. As Rossiter reminded us, an “isobar” is a line on a meteorological map that connects points of equal atmospheric pressure; as such, the goal of Isobar Press is not to publish work based on an exclusive house style, but rather to publish those works that produce the proper level of poetic pressure to land themselves on the isobar line. I can’t quite recall the order of readings during this session, but Rossiter read from Seeing Sights 1968–1978, which is a collection of early poems; Danno read from her wonderful collection, Woman in a Blue Robe; Rossiter, Thompson, and Simons teamed up to read from a suite of haiku written in different voices that appears in Masaya Saito’s new book, Snow Bones; Philip Rowland read from Something Other Than Other, featuring poems that were nothing other than wonderful; and there was also a special guest appearance by C. E. J. Simons, who offered a few sonnets from his 2015 Isobar book, One More Civil Gesture (the only book among the set not yet published in 20160. I find every Isobar publication to be extraordinary, and the offerings from 2016 are no exception.

After the Isobar reading, it was time to run to the ferry. Two days of excellent panels, workshops, readings, and explorations had gifted me a notebook full of new ideas and kick-started the humming brain. I wanted to keep talking with people, and to read more books, to let all of the word-litter that had accumulated drift around and form constellations that would somehow map themselves onto the raw material of the overlooked world passing rapidly by outside the bus windows. I got off the bus with just enough time to grab a Nankai bento and situate myself outside on the upper deck of the ferry. The sun dropped down behind Tokushima as the ship cast off for Wakayama. Seagulls and the breeze, drift of islands, a red buoy floating by against a blue ocean background. Dusk drops down and makes it cold, the perceptual field wide open.

Grab Bag of Inspiration for Writers and Latent Writers

Richard Sadowsky

This year was my fifth time attending the Japan Writers Conference, yet I always feel like an outsider looking in. For five years I penned the “Infotech” column for the years-defunct monthly Kansai Time Out. Today, at best I consider myself a latent writer, while the JWC conference seems to emphasize the participatory: it is organized by and for writers—poets, fiction writers, essayists, and other creative writers. So, does being an aspiring writer count? Surely, there were many in the audience, and attendance is open to all, avid readers included. Best of all, the weekend conference is free of charge! Evening receptions excluded.

The first session I attended, out of general interest, was Karen McGee’s “Violence in Fiction: What Works and Why?” In a key anecdote, McGee spoke of how a haunting scene of violence in Gorky Park, the 1981 crime novel by Martin Cruz Smith, had stuck with her through the years. When revisiting it (shown on a slide), she was surprised to find little actual violence in the spare language used, simply one or two striking details (turning over the body in the snow) that foreboded menace, while the violence took place “off-stage.” McGee offered bullet points on uses (to create a convincing hero or villain, advance conflict, raise the stakes, get the reader’s attention, etc.) while warning writers to avoid gratuitous violence. This brought up the question of whether or not some of Ken Follett’s writing is “torture porn.” Ultimately, to write violence well one should keep several points in mind, including that violence is never just about physical acts; one should foreshadow and make the reader wait for it; allow the reader to choreograph—don’t overwrite.

The next session was one I had looked forward to attending, by American expat and prolific creative nonfiction essayist Michael Pronko, who is a professor at Meiji Gakuin University. In his “Creating Essays and Going Indie” session, he read one story from his Motions and Moments: More Essays on Tokyo, a ¥307 purchase that I already had on my Kindle, from a friend’s recommendation. Pronko spoke a lot about essay writing in general, recommending the easily findable 1865 “On the Writing of Essays” by Alexander Smith (“The world is everywhere whispering essays...”) and “Not Knowing” by Donald Barthelme (1983). He recommended the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik and his book of essays, Paris to the Moon (first chapter: http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/g/gopnik-paris.html). He also recommended Patrick Madden’s “Writing the Brief Contrary Essay” found in The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction. His talk covered tips and tricks (“be organized, original enough; communicate and be unexpected”) for writing that 800-to-1000-word essay. Shift focus (use various lenses) and distances (intimate/expansive), tones (passionate/expressive) and be aware of literary elements (character, conflict, setting, POV, etc.). Moreover, sheer production is very, very important. (Write a lot!) His writing reflects his approach—communicating observations such as “How cool is that?”

In the presentation, “Short Stories: The Art and Science of Plotting,” Peter Marsh gave lots of practical tips, the main one being, “Work out the plot in advance, starting with the end.” This is especially important when short stories are in the vein of O’Henry. Marsh even admitted that he adapted the plot of O’Henry’s “The Paths We Take” for one of his own stories. Which is fair game. A writer is free to invert a plot and make it more complex, as well, he noted. Of course, in every O’Henry story there is a twist at the end that is logical but unforeseen. The surprise can be sprung on the characters in the story and also on the reader, or only on the reader. It can be an epiphany that demonstrates character growth, for example. But it is important that you check thoroughly for logic to avoid a “deus ex machina.” To write a short story, Marsh said to “start with an incident from the jungle of life and make a garden.” You only have two things to flesh out in a short story—the beginning and the end. Other than that, build interest/tension as the story progresses to a sudden drop-off point, drawn on the whiteboard as “Marsh’s shark’s fin graph.” Note: That twist ending must be better than what the reader expected.

The next session I attended was Richard Conrad’s “Cookbooks: An Editor’s Insights.” A former Australian journalist, Conrad explained that a small, skilled team collaborating on the project is required. In his case, four people: the chef/writer, editor, photographer, and art director/graphic designer. After all, the presentation of a cookbook is really an artistic project involving a lot more than typographic design for the stuff inside the covers. Taking photos of food is a specialized skill, requiring an understanding of supplemented lighting for highlights, use of depth of field, and composition. The recipes and photographs must be an exact match, with the recipes short, simple and accurate, tantalizing and achievable, and with steps written in the correct order. Some cookbooks may include a story or autobiography. The editor establishes a style guide, design uniformity, and information architecture. He or she sets out a clear workflow and production schedule in which every dish is cooked, shot, and eaten. Choices must also be made on the type of paper, hard or soft cover, and other components, considering the potential buyer’s perspective: who is going to buy it and why?

On the importance of the appearance, he offered this final dictum: “If you don’t want to eat what’s on the cover, forget about it.” In other words, when it comes to food photography, it’s all about the sizzle: looks activate the taste buds!

In a couple of sessions, notably John Feist’s “Use a Letter in Your Story: A Durable Tool in Telling the Tale” and Hans Brinckmann’s “Autobiographical Fiction: What It Is, and How to Mold Experience with Invention,” the authors primarily read from their books. These sessions did not live up to the educative promise listed in the program. I had expected that I would learn more of the how of the thinking and writing process. Nonetheless the listening experience and the stories themselves were of interest, and I even bought Brinckmann’s The Tomb in the Kyoto Hills at the book table in the rest lounge.

A couple of sessions were designed for fun and to stimulate creative thinking. One was Edward Levinson’s “Visual Stimulation and the Unthinking Mind.” Levinson is a photographer who writes. He showed a series of two juxtaposed images (“diptychs”) and had people come up with sounds, captions or poems. One set of forest walking path images inspired me to write: “The path is there/To walk/Follow it...or not.”

The other was Gareth Morris Jones’s walking tour. Split into groups of four or five, while the university festival was going on around us, each group had a task to accomplish and present to the group, aided by clues provided in an information packet. Ours had to do with architecture and the social fabric, and one of the clues provided us was a photo of the wrapped Reichstag by conceptual artist Christo. Our group decided on the fire extinguisher as a symbol of the positive disruption found all around us. Or something like that. I think the point was a creative group exercise, and the literalists in the group had a tougher time that those who could let go of strict logic to free-associate and create whimsical linkages that made everyone smile and nod.

in an information packet. Ours had to do with architecture and the social fabric, and one of the clues provided us was a photo of the wrapped Reichstag by conceptual artist Christo. Our group decided on the fire extinguisher as a symbol of the positive disruption found all around us. Or something like that. I think the point was a creative group exercise, and the literalists in the group had a tougher time that those who could let go of strict logic to free-associate and create whimsical linkages that made everyone smile and nod.

Although written talks simply read aloud by the presenter leave much to be desired, a talk like Peter Mallett’s “Misanthropes and Monsters: Writing the Unlikeable” generated a lot of discussion in the Q&A afterwards due to his enthusiasm for the subject matter.

On the whole, the Japan Writers Conference is a grab bag of inspiration for writers at any stage of their career, no matter a person’s age or proximity to getting published.

A Long Soak in the Glories of Poetry and Other Moments

Avery Fischer Udagawa

After several years of hoping to attend Japan Writers Conference, I got my chance on October 29 and 30, 2016. This JWC took place in the “Glocal” building at Tokushima University, and featured two days of sessions plus two dinners. SWETer Suzanne Kamata of the university ably hosted the event, with David Moreton and other volunteers. The directors were the gracious and organized John Gribble and David Mulvey.

As a translator of children’s literature, I found JWC useful in that it connected me with people who work with words about Japan—as do I—who do not focus on children. When I presented about the importance of sharing books by Japan- and Asia-based authors with young readers, I felt the need to make somewhat more of a case for this than I often do, and I found the exercise quite helpful.

In my talk “Growing Our Future Audience: Japan and Young Readers,” I said that childhood reading helps us shape our identities and develop empathy for others. I discussed how children are open to diverse forms of storytelling, and how books read in childhood can whet one’s appetite for similar books in adulthood. Stories by Japan- and Asia-based authors have earned several children’s literature awards recently, but it is hard to sell them in the inward-looking English language markets, and to keep them in print. I invited listeners to think with me about how we, ourselves, learned of favorite books as kids, and how we can connect young people today with works from Japan. My slide show, linked below, shows covers, authors, and translators for a number of recent, share-worthy children’s and teen titles. Consider giving some of them this holiday season!

If presenting at JWC was a rewarding challenge, hearing others speak was pure delight! I first heard Diane Hawley Nagatomo of Ochanomizu University discuss “Writing for Academic Publication.” With info-packed slides, she reminded us that clarity, concision, and concrete examples matter, even (perhaps especially) when writing for academics. “Snooty,” long-winded writing may not get read in this age of online research. Nagatomo recommended resources for both studying and leading discussion of good academic writing, including “Professor, Your Writing Stinks” by Steven Pinker (in The Chronicle of Higher Education, 3 October 2014), The Sense of Style by Pinker, Line by Line by Claire Kehrwald Cook, and They Say / I Say by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein. Nagatomo noted that the book English for Writing Research Papers, by Adrian Wallwork, makes many of the points that she emphasizes, including “break up long sentences.” She also reminded us to “revise, revise, and revise some more.” I left the talk eager to read Nagatomo’s own writing, in her new book Identity, Gender, and Teaching English in Japan.

Later, Holly Thompson’s sessions “Verse Novels Crossing Borders” and “Poems with Plot—A Narrative Poetry Workshop” afforded a long soak in the glories of poetry. The top line of Thompson’s handout on verse novels read, “Poetry is a magic carpet that can transport readers across borders of language, class and culture”—and indeed the works she shared took us from Tokushima to Australia, Vietnam, Cuba, and points beyond. She demonstrated how the “flexibility and interiority” of poetry, plus its spare nature and musical aspects, help authors reel in “readers of all ages who find prose off-putting,” including English learners. Poetry also allows the space to pack in complex storylines. In the narrative poetry session, Thompson asked us to tell our own stories through poetry, by reading mentor poems and using them as prompts. For example, “The Gift” by Li-Young Lee shows a man removing a splinter from his wife’s thumb, while recalling how his father took a splinter from his own palm years ago. This gave us ideas for using an object to link our distant past with the present. The handouts noted that many further poems-prompts can be found at poetryfoundation.org and writersalmanac.publicradio.org. Some verse novels I wanted to read after these sessions included By The River by Steven Herrick and Garvey’s Choice by Nikki Grimes. Thompson’s own latest verse novel is Falling into the Dragon’s Mouth. She blogged about her experience of JWC 2016 here:

http://hatbooks.blogspot.com/2016/11/snow-bones-and-japan-writers-conference.html

As Thompson’s blog post indicates, a title called Snow Bones figured prominently in JWC 2016—particularly in a reading of poetry published by Isobar Press. This session featured individual readings by Isobar Press publisher Paul Rossiter and poets Yoko Danno, Philip Rowland, and Christopher Simons. It also featured the trio of Rossiter, Simons, and Thompson reading from Snow Bones by Masaya Saito. Saito’s innovative volume contains four narrative haiku sequences spoken by multiple voices; at JWC, the three-voice sequence “Countryside” was read out. Each reader became a character in the world of Saito’s narrative; while the characters never engaged in dialogue, their haiku commented on similar aspects of a shared world. The reading spurred me and surely others to attempt similar daring experiments—and to check the list of titles at isobarpress.com!

Finally, I found a panel called “Inspiring Fiction: Where Do You Get Your Ideas?” to be both enjoyable and a font of reading recommendations. The panel featured Sara Kate Ellis, Suzanne Kamata, Elaine Lies, Karen McGee, and Wendy Jones Nakanishi, whose professions range from professor to journalist and whose fiction runs from realistic contemporary to murder mysteries and science fiction. I heard Nakanishi, a specialist in eighteenth-century English literature, describe some of her fiction as “catharsis” inspired by vengeful thoughts—how refreshingly human!—and Kamata describe conversations overheard, folklore, and travel (including disastrous travel) as fodder for her stories, such as the Australian place name that inspired “The Rain in Katoomba”. Several panelists mentioned news as inspiration, and one mentioned dreams. All highlighted the importance of life experiences. A takeaway was: I must read these writers’ work! Much can be found with a click of the mouse. Ellis’s story “The Squeaky Wheel” is in full text and audio at SolarpunkPress.com [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aThm4leBYsc

[url=https://solarpunkpress.gumroad.com/l/XYbUh]https://solarpunkpress.gumroad.com/l/XYbUh[/url]]; her story “The Test Audience” appeared in the Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine Issue 60 [no longer available]; “Wax” by Lies is in full text at FabulaArgentea.com [http://www.fabulaargentea.com/index.php/article/wax-by-elaine-lies/]; McGee’s story “Door to Door” appears in the now-free e-anthology 9Crimes [https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01J6M5DCC/ref=cm_sw_su_dp] and her story “Vision Zero” can be read online at Hidden Chapter [https://www.hiddenchapter.com/2016/06/30/vision-zero/]. Stories by Kamata are collected in The Beautiful One Has Come, sold in paperback and ebook [https://www.amzn.com/1936214385] and her story “Blue Murder” is online at the Asia Literary Review [http://www.asialiteraryreview.com/blue-murder]; Nakanishi’s novel Progeny, which bears the pen name Lea O’Harra, is also in paperback and economically priced ebook [https://www.amzn.com/B01IHJUNJS].

(Originally written for the SWET Website, January 2017)