November 29, 2021

Writing from Japan: English-Language Newspaper Columnists in the 1980s and 1990s—Angela Jeffs

As part of SWET’s 40th anniversary celebrations, we are chronicling the memories and experiences of some of the many columnists of that era. We have asked these writers to reflect on how they wrote and communicated back in the pre-digital days, a time when Japan boasted four English-language newspapers and plenty of magazines looking for English-language contributors. It was a golden age for Japan-based writers before the Internet and social media changed the way we live and work. This is the fifth installment in the series.

What Can I Say, Japan Times, but Thank You!

by Angela Jeffs

When I arrived in Japan on April 1, 1986, the last thing I was thinking to do was work. A breakdown at age 45 had led to selling my home, spreading belongings among friends all over London, and encouraging my children to fend for themselves. I needed to change my life, and an invitation to spend some time in Japan seemed a good way to start. My therapist was less encouraging: “As far around the world as you can go, hard language, hard for women—can you not see that once again you are making life hard for yourself?”

A month extended into three and then six. I had arrived deeply tired and completely lost. But the freedom and lack of responsibility proved hugely liberating. Staying in a one-room apartment in a danchi in Chigasaki, I had little to do, so I bought a bicycle and cycled up and down the Shonan coastline, exploring. I read every book I could find about Japanese history and culture. I joined a class in Yokohama to learn Nihongo. Three alphabets, or scripts? That was a shock.

Back “home” I had worked in publishing since the late 1960s. I went freelance in 1973, and was never out of work, editing and writing for magazines and books, creating publications for corporate clients, even launching a small book packaging company with a graphic designer partner. But in Japan I swiftly realised I was sick of editing other peoples’ words. I wanted to write my own. And, oh my goodness, there was so much to write about.

I think my very tentative, almost apologetic letter to the Japan Times, asking if they might be interested in anything I wrote about crafts – a speciality back in the UK – may have been handwritten. When I had a very nice response, my (now) husband Yasuyuki (Akii) Ueda borrowed an unused portable typewriter from his brother. Luckily his brother forgot all about it; it never went back. And so late 1986 began several years of working with carbon papers and Tippex. Having never learned to touch type, so lavishly needy was my usage of that correction liquid that I should surely have bought shares in the company.

After a few months of writing about this and that, I suggested a Japan Times column called “People,” which would involve interviewing interesting persons visiting Japan. The timing was not good; the paper had just launched several new columns and there was no room. Six months later, I got a call: the paper had come up with a great idea for a new weekend column. It would be called “People.”

For the next 24 years, I sought out subjects on a weekly basis and became increasingly fascinated that individuals would be so open and trusting with an interviewer. It was as if at some point I pressed a button and off they would go, divulging the most personal information. To this day, I carry many secrets, and will do so to my grave.

I had learned early—and the hard way—that to disclose anything “off the record” would make me no friends, and a journalist not to be trusted. A year or so after arriving in Japan I had interviewed an author in Kobe for The Magazine, and keen on a scoop, divulged information I had been asked not to use. She never spoke to me again.

My early years with the Japan Times were not easy. My confidence levels fluctuated like crazy, and looking back now, I suspect some of my editors were as unsure and struggling to validate their position as I was. My husband recalls weekly spurts of anger on reading how changes had been made to my copy, and all my hard-learned English-style English had been Americanised. Color for colour? How simplistically lazy. Practice replacing practise? I mean, honestly...

I got tired of arguing when it became clear I was never going to win. Or maybe Japan simply made me increasingly accepting of rules and compromise. Anyway, I choose to believe we have all forgiven one another over the years, and I remain in touch with several of my editors. Sadly though, I have not heard a single word from my last editor, with whom I worked closely over a decade (often having lunch and listening to his problems) since my last piece was published in the paper.

That last piece was not a profile but one of the occasional features I wrote, in this instance about the historic Tomioka Silk Mill in Gunma Prefecture that was seeking World Heritage Status at the time. It was published the day after 3/11, when Japan was reeling from the after effects of the earthquake and tsunami and in terror (it is not an exaggeration to say this) of what was happening in Fukushima’s nuclear plant. Needless to say, my words were irrelevant to one and all, except perhaps UNESCO’s World Heritage committee based the other side of the world in Europe. I like to imagine that the paper's coverage helped, because the following year the mill’s application was approved.

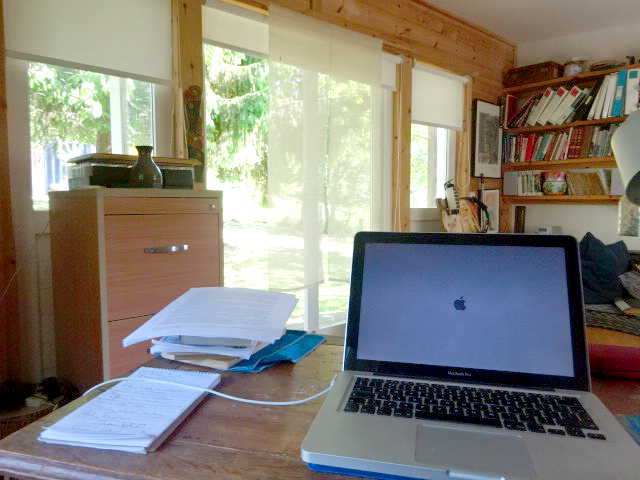

My articles written before 2004 are not available online and I kept no carbon copies of the early interviews. My memory is playing tricks as never before, so I can remember only a few profiles from the first few years. I kept clippings of all the printed articles in folders from about 1990, which is when I bought my first computer. Being Japanese and a computer man, Akii (who I married in 1989) came with me to Akihabara and we shopped for an early Apple desktop. It was white, square and clunky, but miraculous.

Even more miraculous was the fax that was assigned to me by the Tokyo General Agency (TGA). I was told it was one of the first such machines used domestically (meaning in a home rather than an office). TGA had been established in 1985 by two Japanese women, to help foreign families relocated by corporate employers abroad find their feet in the city and Japan. I interviewed President Tomoko Takata and as a result was asked to help develop a client magazine, TGA Eye, and write a monthly article (“Eyeopener”).

I had little idea initially that my Japan Times business card would open so many doors, not just in Japan, but internationally. It led to becoming the Japan stringer (correspondent) for Asia Magazine, based in Hong Kong (1991–1999). I wrote major articles, short newsy snippets and contributed to a travel series of venues around Japan that were eventually compiled into a paperback, Discover Asia. I received expenses for this too. There was so much money around back then, and I could not believe how much was winging its way in my direction.

With the Japan Times, the situation was a little different. I think I was paid ¥15,000 yen per article, and this never changed, despite my pleas for minimal expenses to cover my travel into Tokyo first from Chigasaki (1986–1988), then Kamakura (1988–1990), Hayama (1990-2000) and Zushi (2000–2012). I also had to use my own money to pay for film and processing, since I was taking my own photographs. I hardly made a profit this way, but rode on the generous backs of all my other employers. It did leave me stretched rather thin on occasion. When I took on a book, Insider’s Tokyo: The Alternative City Guide (pub. 2001)—commissioned by Times Books International in Singapore—I pushed myself beyond the limit. We all suffered the consequences: missed deadlines; stress-related ill health, arthritic knees.

How did I juggle all this? All I know is that even when I took on regular shifts in NHK’s Asiavision (where I was working on 3/11), it was the Japan Times that somehow held me together. It was the backbone that patiently supported me in meeting well over a thousand amazing people over more than two decades: actors, musicians, business leaders, designers, politicians, farmers, chefs, adventurers, volcanologists, artists and artisans, sports men and women, activists, celebrities . . . even a couple of goddesses. Many I have to admit have become ghosts, especially since I have no record of our paths crossing. But some memories are as clear as day . . .

• The representative from Kunaicho (the Imperial Household Agency) who was responsible for organising former emperor Hirohito’s funeral in 1989.

• Danish graphic designer (and jazz buff) Per Arnoldi two-timing in Tokyo, i.e., he had two exhibitions running simultaneously. This was 1991, peak Bubble-economy days.

• Lunch in 1993 with Nell Newman, who was visiting Japan to promote pretzels under her own off-shoot of a company name Newman's Own Organics. In one moment I could see in her face her mother, the actor Joanne Woodward, and in the next, her father Paul Newman.

• Father and son Ejiri Koichi and Munekazu of Sawada Orchid Nursery in Chiba Prefecture, who in the early 1990s were leading the way in growing and exhibiting this beautiful flower to international acclaim.

• The former chairman of Japan Airlines who was a gem to speak with (sadly most corporate leaders had little to offer beyond an interest in go or golf).

• Lady Nobuko Albery, based in Monaco, who was determined to open up the taboo subject of menopause in her country of birth.

• The table tennis child prodigy “Ai-chan” Fukuhara who was in training for the Asian Games.

I could go on, but I think not. Suffice to say that I interviewed at least one Japanese person a month, and was pleased when a reader would comment that I had helped them understand not only the country, but its people, so much better ...

My language skills were limited in those days, so I relied on friends and my partner. After interviewing Ken Joseph Jr. of Japan Helpline, he offered to help in any way he could, opening doors that even my Japan Times business card could not. He was a man who moved between Japan’s many worlds with ease, one moment introducing me to yakuza, the next, close friends of the Imperial royal family. Their link? Christianity.

There was one group to which he belonged at NHK. There was also one at the Japan Times. This led to distrust among many, and my relationship with him was viewed as questionable. The truth is that I was using him as much he ever used me. While not agreeing with his somewhat fundamentalist views on religion, I always saw him as an asset, and my husband and I always thought of him as a good friend. When Akii went with him and a group of other volunteers to Tohoku after 3/11 to help dig out homes, it was he that Ken trusted to locate and pack a Geiger counter.

I suppose it was living outside Tokyo that made me independent of the expat community. However, I did need the community on occasion, and was invited to more than a few high-flying events. This made me a bit of a maverick, I’m afraid. The Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan is a good instance. I never joined, but instead slipped in and out when I chose to, to meet someone for a drink, to use the library (an invaluable resource) or to attend a press conference. I even took my mother there in 2001 for lunch, to impress her. How I got away with it, I have no idea. I do remember being stopped one day by Andrew Horvat, who admonished me sternly: “You can't keep doing this, Angela.”

I think it was Geoffrey Tudor, who I interviewed in 2007, who saved me. As the international PR representative for Japan Airlines, he was exceptionally active in the press club, organising my book launch for Insider’s Tokyo, and ensuring I was on the mailing list for a JAL calendar every year until he retired. I miss that calendar. Damn it, I miss him.

I interviewed many impressive authors and experts on Japan, many of whom are sadly no longer with us. One of my earliest interviews, with the British author Alan Booth, left me in awe. When I met Donald Richie, I could hardly speak. I exchanged some words with Edwin Reischauer in passing . . . he passing through his kitchen as I interviewed his wife Haru about her memoir Samurai and Silk: A Japanese and American Heritage (1986). As for Edward Seidensticker, I think it was Ken who brought us together to help promote Ed’s own memoir, Tokyo Central (2001).

All these illustrious names, and yet I never really got to know any of them. Not because they were unfriendly, but because I felt intimidated, ashamed, a fraud. They had credentials. I felt I did not. This is also why I never joined SWET. I feared they would swiftly find me out. So I remained aloof in isolation, outside, yet always moving forward.

When columnist Jean Pearce found love later in life and left Japan in the summer of 2000, a whole new world opened up to me. We had only crossed paths once at a cricket match in Yokohama but apparently it was she who suggested I pick up her role as Japan Times’ agony aunt. I’m not sure if this is true but it’s what I remember being told. It was not easy following in her footsteps. Jean had become an institution, answering readers’ enquiries for over 40 years. I soon found myself in trouble.

The days of people wanting to know where they could buy French cheese or find an English-speaking dentist were long past. By the new millennium the demographic of the foreign community had changed and queries were increasingly difficult to research and answer: questions about visas, divorce, and child rights. They required facing bureaucratic challenges and having good Nihongo. Having spent two decades in English-language publishing, I was not equipped. Again Ken Joseph came to my rescue and for a while we co-authored the column. But I was not happy. And neither I believe was the paper.

There was another matter. In 1999, I left a stock of articles to print while I was away, and took a month off to go to Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile to chase down my grandfather's ghost. On my return, I had my last breakdown and was forced to finally face my demons. Why was I so driven? Why did I shoot myself in the foot every time I came anywhere near achieving “success”? This is one reason why I became increasingly interested in alternative therapies and introducing them to the public via the paper. On more than one occasion I would be contacted by my editor, with the plaintive request to satisfy more mainstream interests: business, sport, entertainment.

Everything changed again after 3/11. All I wanted to do was write about recovery, transition, and change. I hunkered down in my office in Zushi, and deliberately slowed my pace. In late 2012, my husband and I decided to move to Scotland, where my mother’s croft had been standing empty since her death in 2007. This decision was far from easy. But Akii no longer wanted to be a sarariman, and in Japan we had to pay rent.

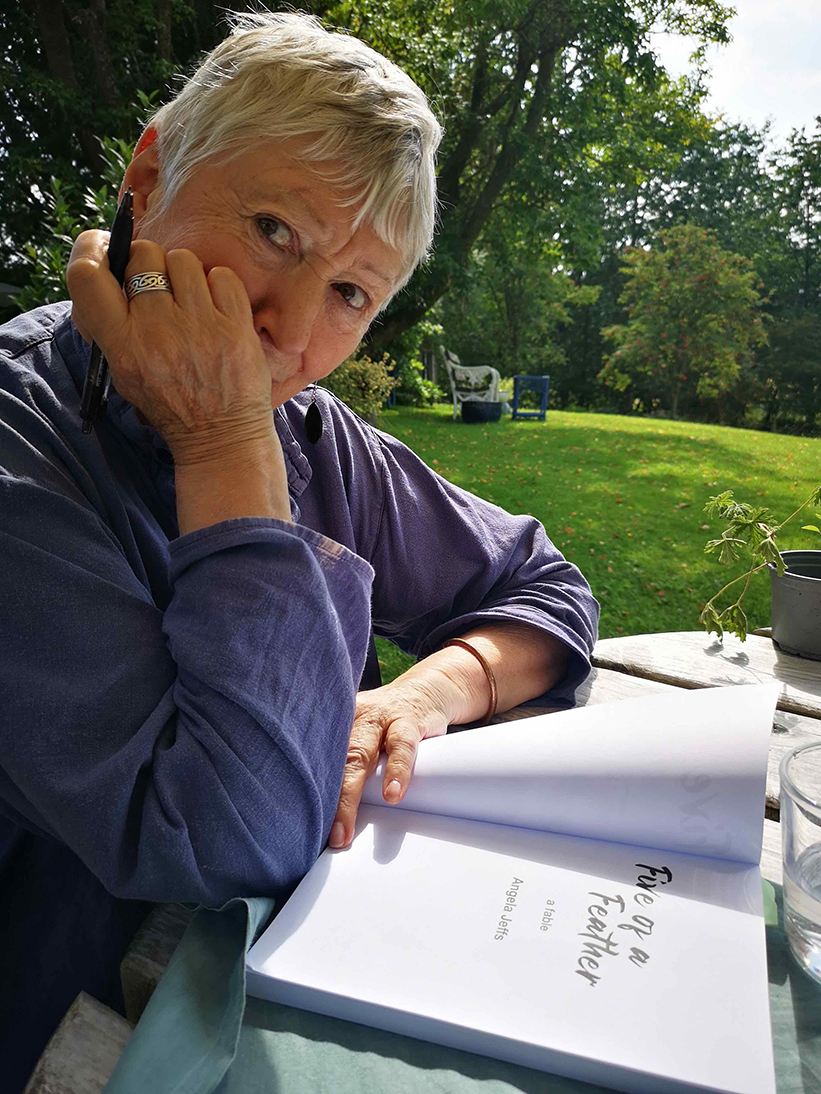

We came to Scotland for a year, and eight years on are here still. (I would return to Japan tomorrow but Akii likes Scotland: “No stress,” he says.) In this time, I have independently published three books: Chasing Shooting Stars (2013) based on tapes made during my South American pilgrimage, Household Stories/Katei Monogatari (2017) about our home in Zushi; and Five of a Feather—a Fable (2020), which blends fact with fiction and a handful of magic.

I continue to offer a programme of therapeutic creative writing I first developed in Japan in 2003, Drawing on the Writer Within. I blog on my website on an irregular basis. And have spent lockdowns organising two diaries, with contributions from student writers I have worked with here and there, now scattered around the world. The first diary, covering December 2020—39 writers from seven countries who each took a day, is now archived in our local Perth Museum. The second, with writers taking fortnightly blocks throughout 2021, is coming to an end, and I shall spend January 2022 knocking it into shape, again for the museum’s covid archive.

Beyond that, who knows. Contributing to Carolyn Hashimoto’s online magazine Skirting Around satisfies the need for personal challenge right now, and I am excited about an idea I have for another piece of fiction.

The other day, I was talking with my daughter-in-law about how difficult it was to write this piece, because my time at the Japan Times seemed in retrospect to be so full of trials and tribulations. She laughed. “Really,” she said, “Are you sure?”

She reminded me that in 2003 I sent out an e-mail (which she remembers verbatim) about my possibly resigning from the paper. But in that same e-mail I also wrote about what an honour and privilege it was to have met and interviewed so many eclectic and interesting people who had been kind enough to share their lives with me. This unusual “job” took me to new places and gave me the opportunity to interview and work with people I wouldn’t have met otherwise, often ending up as friends.

So what can I say, Japan Times, but “Thank you!” (www.angelajeffs.com)

___________________________

Angela Jeffs grew up in Warwickshire, trained in drama and Laban movement in Yorkshire, then moved to London in 1962 (along with the Beatles). She worked there in publishing for two decades, as an editor, development and consultant editor. Arriving in Japan 36 years ago for what she assumed would be a holiday, turned into 26 years of exhilarating hard graft. Now living in a rural community in the foothills of the Scottish Highlands, she describes herself as as a rather more relaxed author, writer and writing guide. Writers never retire, she says.