January 7, 2022

Writing from Japan: English-Language Newspaper Columnists in the 1980s and 1990s—Janet Ashby

As part of SWET’s 40th anniversary celebrations, we are chronicling the memories and experiences of some of the many columnists of that era. We have asked these writers to reflect on how they wrote and communicated back in the pre-digital days, a time when Japan boasted four English-language newspapers and plenty of magazines looking for English-language contributors. It was a golden age for Japan-based writers before the Internet and social media changed the way we live and work. This is the sixth installment in the series.

Writing for Japan Times and New Opportunities in Japan

by Janet Ashby

Coming to Japan in 1975 to study at the Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Studies in Tokyo (now Yokohama) gave me many unforeseen opportunities. For one, I discovered from talking with graduates of the program that it would be easy to support myself in Tokyo without a nine-to-five job. Living in a four-mat room, I learned translating through assignments from a translation agency and then worked on the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, the kind of ambitious undertaking rarely seen today. I don’t now remember why I decided to write a newspaper column, first one suggesting Japanese-language television shows, movies, manga and books for beginning students of Japanese and then later on one reporting on Japanese books and publishing. I think I may have been inspired by my own experiences on coming to Japan after studying Japanese at universities in the United States, when, like Japanese students of English, I could read fairly well but had very poor listening and speaking skills. Since this was still, in 1975, long before video or YouTube, before Cool Japan or the US manga boom, most of the materials for studying Japanese were very academically oriented, aimed, say, at budding scholars of Buddhist studies.

Perhaps the example of a book I saw listing suggested easy-to-read books in English for Japanese learners of English played a role, as did the opportunity for nonprofessional writers to have a Japan Times column, such as the humorous columns by American businessman Don Maloney that I enjoyed, later collected as Japan: It’s Not All Raw Fish (1975) and Son of Raw Fish (1977). At any rate, I obtained a meeting in 1990 with an executive at Japan Times through the introduction of Ms. Nobuko Mizutani, author with her husband of the Japan Times column “Nihongo Notes” and one of my former teachers at the Inter-University Center. The executive seemed interested in my idea but asked me to do a month or two of sample columns first.

After mailing in the sample columns, I got approval to go ahead and met once with the Japanese editor in charge of such pages. Then I would type the column, appearing under the title “Time Out Japanese,” weekly and fax it to him to be edited for length and input into their system by an American native speaker editor. There was a large turnover in the latter position, which was filled by recent college graduates with varying degrees of competence. I learned to ask for proofs by fax to check for strange changes and cuts that altered the meaning, transmitting my corrections by phone. At first I wrote my columns on an Olivetti portable typewriter I had brought with me to Japan and then an Oasys word processor from Fujitsu that I bought in Akihabara.

I tried to choose materials that I myself found interesting and that offered a window into Japanese culture like the TV quiz show “100-nin ni kikimashita” (We Asked 100 People), the comic strip and animated TV series “Sazae-san,” or the Otoko wa tsurai yo movie series. Most of my research was in visits to bookstores and reading weekly TV guides and the weekly city information magazine Pia.

After a while I started to have a harder time finding topics suitable for beginners or intermediate learners and tired of the relentless grind of doing a column every week, and in 1991 I switched to a longer monthly column on Japanese books and publishing that allowed me to cover more difficult works in more depth; I continued that column, which appeared on the "Bilingual" page, for 13 years until the end of 2004. I was interested in learning more about the book scene in Japan and was also hoping to find something I might want to translate one day.

I spent a lot of time searching for good topics, visiting bookstores and scanning the book pages in newspapers and weekly magazines as well as the news magazine Aera and monthly magazines like Bungei Shunju at Hibiya Library or the local library. I wrote about bestsellers, the winners of major literary prizes like the Akutagawa Prize, genres of books, and publishing news like the start of the BookOff chain of used bookstores or the reports on that year in publishing appearing in December and January in newspapers and magazines. I would also check out Da Vinci, a slick monthly magazine on books aimed at a younger readership, after it started publication in 1994.

Once I had decided on a topic I would research biographical information on that author and their body of work. Since this was before one could just google that information, I relied on the blurbs in their published works, Japanese reference works, and the interviews I could find in newspapers and magazines—sometimes consulting a periodical index from the National Diet Library or asking for a data search at the International House library where I had a library membership. And then of course I read the book, or at least a major chunk of it.

Obviously doing the column was far from cost effective in view of the hours it took to do it. It was, however, interesting to learn more about Japanese authors and publishing, although I never did find anything calling out to be translated. I realized, in fact, that very few works of Japanese nonfiction or non-literary fiction lend themselves to a straight translation into English, at least for an American readership.

I received very little feedback on the column, and there was no interest from Japan Times in publishing the columns in book form. Doing the column did, however, lead to being contacted for appearances on two NHK television shows and one NHK radio show, another opportunity I doubt I would have had back in the United States. The first, for a weekly NHK book show, was interesting from an anthropological standpoint. Two other foreigners and I were asked to bring in a Japanese book we had read and then were each asked the same three questions. Toward the end of the 10- or 15-minute segment we had gotten warmed up and started having an actual conversation but then the time was up and filming stopped cold. It was egalitarian in that everyone had equal time to speak, but it resulted in a very boring piece of television.

The second was an hour-long show for NHK World, which at the time could only be seen in Japan and a few places overseas. This show was about that year in Japanese books with me doing an intro in a Japanese bookstore and then interviews with the editor of a Japanese book magazine and the author Ishida Ira. This was all done in Japanese and then dubbed into English. I had input into what the show covered but ultimately found it a frustrating experience as it was the director who had the final control, and he was more interested in visuals than content. The third NHK program was another roundup of that year’s bestsellers, a discussion in Japanese with an interviewer for NHK radio, which went off smoothly.

The second was an hour-long show for NHK World, which at the time could only be seen in Japan and a few places overseas. This show was about that year in Japanese books with me doing an intro in a Japanese bookstore and then interviews with the editor of a Japanese book magazine and the author Ishida Ira. This was all done in Japanese and then dubbed into English. I had input into what the show covered but ultimately found it a frustrating experience as it was the director who had the final control, and he was more interested in visuals than content. The third NHK program was another roundup of that year’s bestsellers, a discussion in Japanese with an interviewer for NHK radio, which went off smoothly.

I also received a few requests for reprints of a column in annotated texts for Japanese students of English.

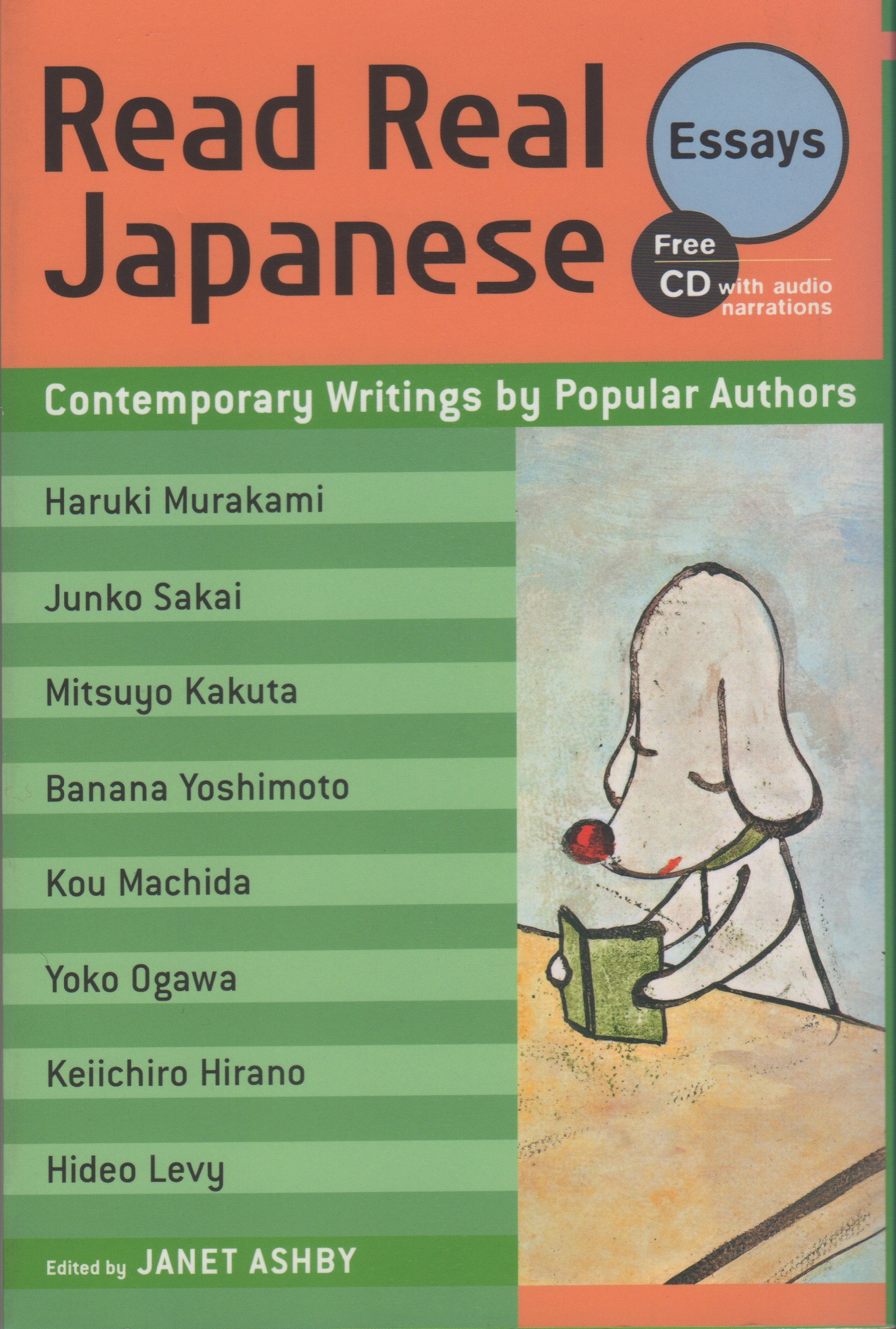

So there was no fame or fortune from doing the two columns, but I did learn more about popular culture in Japan, a background which came in useful for the two books of Japanese essays that I selected and annotated for English-language learners of Japanese, Read Real Japanese and Read Real Japanese: Essays, published by Kodansha International, another institution sadly gone now. There was also personal satisfaction in doing a professional job of researching and presenting material of interest to at least some readers in Japan. In this respect, I remember the wise advice of veteran translator John Bestor to young translators at an early SWET panel discussion I attended: always do as good a job as you can even if the Japanese client can’t tell the difference, for the sake of one’s own self-respect.

_______________

Janet Ashby is a writer and editor based in Tokyo. Originally from upstate New York, she attended the University of Michigan (BA, linguistics) and the University of Wisconsin (MA, Japanese history). She has served as a translator and editor, translating and editing for the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (1979-83) and checking translations for Newsweek Japan since 1985. She is the author of Gaijin’s Guide (Japan Times, 1985), Read Real Japanese (Kodansha International, 1994), and Read Real Japanese: Essays (Kodansha International, 2008).