May 4, 2023

Entering into the World I Created: Interview with Karen Hill Anton, author of “A Thousand Graces”

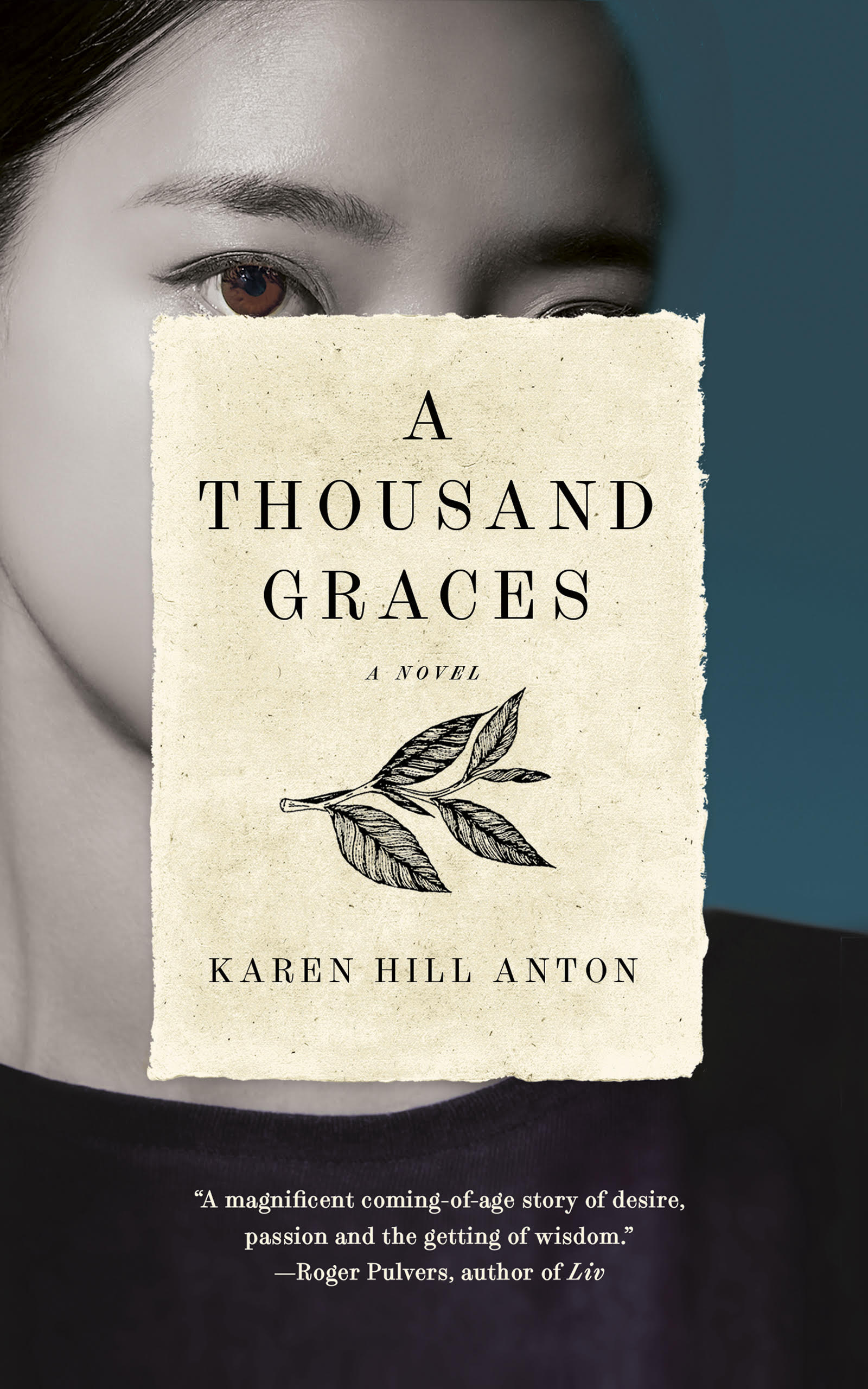

Karen Hill Anton is well known for her columns in the Japan Times, which she described in an article for SWET’s series on English-language newspaper columnists. Her memoir, The View From Breast Pocket Mountain, beloved by a wide readership, has earned three literary awards. She spoke to SWET about her memoir at length for a SWET Talk Shop in August 2021, available on YouTube, and again in October 2022 about the craft of memoir writing. Now fulfilling a long-nurtured dream of publishing a novel, Karen agreed to talk to SWET about how this new phase of her writing career began to unfold. To read more about Karen and buy her books, see her website.

We understand you began writing the novel that became A Thousand Graces many years ago. What propelled you to write it? Tell us a bit about the writing process—What inspired you? What gave you pause, and why did you decide to publish now?

Although I do not have the exact date, I began writing the novel around 1996. I wasn’t sure where I was going with it, lost interest, and put it in my infamous “third drawer” where I keep all my writing drafts and notebooks. After my memoir came out, I assumed that might be it for me publishing books. Then one day in an email exchange with Roger Pulvers, he wrote, in part: “…you will find as you continue to write—and I hope you do! …” That was it, and enough: I took it not only as encouragement, but expectation.

Let me here say how meaningful and impactful it can be for a writer to have the encouragement of writers she respects and admires, and who believe she has talent. Roger Pulvers (writer, theater director, translator, essayist, poet, and more) wrote the most wonderful editorial review for my memoir, and I count him as a dear friend. At an earlier time, Donald Richie always expressed his appreciation for my Japan Times column “Crossing Cultures,” and I can quote him as saying: “I have long been an admirer of your column—it’s the first thing I read on the day it appears.” Donald befriended me, and was instrumental in the columns being published as a collection.

In any event, I took out the draft of the novel (I hadn’t looked at it for years) thinking I might have 50 pages, and was quite surprised I had more like 200. I began re-reading, and again, much to my surprise, thought it was an interesting story (at least the promise of one, as it was not then completed). Especially, I was captivated by the characters. I felt it was a pity that I’d abandoned them. I thought they were interesting people, and most importantly, I cared about them. I wanted to finish their story.

I no longer remember what propelled me to write the story in the first place. But I do know I knew the name of the main character, her path, and the title of the novel before I put pen to paper.

People are very familiar with your memoir and have embraced it. Do you think they will be surprised to find you have chosen to write a very different genre—a novel—this time?

They might be surprised. But of course, it isn't because people have read my memoir that they know everything about me, everything I’ve done, everything I might do, everything of which I’m capable.

What would you like readers to take away with them after reading this novel?

I haven't really thought about that. I think reading fiction is a highly subjective experience. I don't have a message. It’s a story. Pure fiction. I created the characters, and the situations they’re in. Jane Eyre and Anna Karenina are two of my favorite novels. If Charlotte Brontë and Leo Tolstoy had a message, I don’t know what it is. But I do know those books spoke to me, and I found them endearing.

The characters are beautifully crafted in great detail. Was there any character that was especially difficult to write?

No. I feel like I know these people. But it’s storytelling, my characters are not modeled on anyone I actually know, or knew. They are not even composites. I think my sensibility, awareness, observation, experience, and of course, imagination, were what helped me draw these characters in detail. I knew what clothes the main character, Chie, would wear, and how she’d wear her hair. I knew she loved soba but didn’t like fish. I knew her mother’s origin story, and that her father, a tea and mikan farmer, enjoyed a particular brand of sake in the evenings.

It is often said it is a great challenge to write a character of another nationality in a way that is believable to readers and yet you have done so very skillfully. In fact, it almost seems like a Japanese novel that has been translated into English.

Yes, I guess it can be seen as a “great challenge,” but I did not feel daunted by the prospect, and never thought about it as a challenge while I was writing the novel. I never thought I was writing about Japanese people, but people. I have not written about them as stereotypes or caricatures. Having now lived in Japan, among Japanese people, for almost half a century, this is my milieu. I do not think it’s surprising that I would have developed, absorbed, Japanese sensibilities, and have a keen sense of the people with whom I am in community. I can hardly imagine writing about people who live in the Pacific Northwest, a place I’ve never been to—but then again, if I employed my writer’s imagination, I might be able to write about them, too …

Everywhere in the book we can observe very carefully crafted word images, scenes, transitions, characterizations—what was the part about writing fiction that you enjoyed the most? Spent the most time on?

I’d say it was entering the world I created. I always felt I was right there with my characters. Their world was my world while I wrote. And I imagine many writers of fiction would say that much of the writing takes place in an almost dream-like state. It is not a stream-of-consciousness kind of state of mind, as the writer must always be present, choosing not just the right word, but the best word, aware of the weather, the smells, know who's talking and what they will say next. I spent a lot of time developing the characters, I wanted to know everything about them, contemporaneously, and earlier. It mattered to me what they ate, what colors they liked, how they expressed affection or dissatisfaction, what time they went to bed. These are all mundane things, but I think they help bring the character to life.

Often a scene will come to a climax and then end with a very vivid image, leaving the rest to the reader's imagination. Was that a technique you devised from the outset?

Oh, that’s interesting to hear. No, it was not a devised technique. It was not contrived. It is simply how I write. If I have a style of writing, I am not aware of it.

What fictional devices were ones you wanted to stay away from and deliberately avoided?

Well, I did not want to use quotes for dialogue. I’ve always found them distracting. But I could not avoid them as I do not think I was a skilled enough writer of fiction to be able to pull it off. Roger Pulvers does it excellently, as can be seen in his novel Peaceful Circumstances.

As a firsthand observer of those times, did you feel a desire to be a translator or chronicler of Shōwa era Japan for modern-day readers?

Not really. But as I wrote the novel, I did feel a certain wistfulness for that period. It was when I first arrived in Japan (1975) so some of the images of those early days have stayed with me. And of course, I have now been here long enough to know what has disappeared, and to feel nostalgia for it. It would never have occurred to me to take photographs of daily life from that period, for example, of the local restaurant where we used to buy unagi no kabayaki (grilled eel), where the master, who always had a welcoming smile, stood grilling the unagi over charcoal, and how when you were on that street you would be enticed by the aroma long before you got to the store. Inside, there was a small koi pond that delighted our children, a large calendar on the wall, and a poster or two of enka singers who’d come to perform in the neighborhood. The television was always on. On the small tables were waribashi (disposable chopsticks) in a plastic container and a small canister of sansho (Japanese pepper). There was no one to take over when the master got old and they closed the store. There’s not a day I pass by where the store used to be that I don’t remember and miss it. And I swear I have never tasted unagi no kabayaki as good since.

Of course your own experience/observations profoundly inform the novel, but where did you turn when you needed more information? (For example, about tea plantation work?)

I did not do any research for this novel. All observations are my observations. I’ve picked tea (only once!) with a baby tied to my back. Living in the countryside, I remember when my neighbors picked tea, what they wore, the season, the process of drying and packaging, and how special it was to be given a packet of shin-cha, the new tea, sometimes while it was still warm.

You have independently published both of your books via Senyume Press. Is there a story behind how you chose that name?

I made it up. It could be loosely translated as a thousand dreams, but I just wanted something relatively simple and easy to say. And since I had done a stylistic calligraphy of yume (dream) I could use that as the logo.

And have you found independent publishing a satisfying approach?

Well, yes. And no!

I’ve found having complete control is what works best for me. I would not have worked well with a publisher who told me, for example, to remove chapters that I wanted to keep, or to change a character in a way that did not meet my image. I would not want them to choose the title, or the book cover—and of course, publishers do all that. Also, I am not a young person and did not want to be on a publisher’s schedule—it would not be unusual for it to take two years before my book saw the light of day. And lastly, many publishers now employ “sensitivity readers”—which are effectively censors. I would not have tolerated that.

As for the “no” part, I had to put together my own team: book project consultant and developmental editor (for the memoir), copyeditor, proofreader, formatter, book cover designer. Aside from the cost, which is considerable, it was a lot to focus on, and coordinate. Frankly, with the novel, I was thoroughly exhausted by the time it was released.

What advice would you offer others who wish to publish independently—regarding both the actual publishing process and the ever-so-important book promotion aspects as well?

My first bit of advice would be to say “independent” does not mean unprofessional. I do not mean to be unkind, but I’ve seen far too many independently published books that look like they were put together in the author’s spare time. For all I know, they may be good books. But when I see a cover obviously not designed by someone skilled at that task (and yes, a book is judged by its cover), a book that is poorly formatted, and that’s obvious on the first page, and I read a first chapter that is rambling and incoherent and could benefit from a comprehensive copy edit, I think that writer did not approach publishing independently seriously. I will add that I have an especially high regard for what copyeditors do, and willingly pay their fee.

Still, some writers are quite skilled at copyediting, and proofreading, their own work, and can save themselves those expenses. Formatting a book isn't the most difficult task and I can see writers choosing to do that themselves. But I think it is a mistake to think that you, the writer, can do everything. I can write a book. I do not think I could design a book cover. That’s a very particular skill. (But let it be known: I was hands-on and very much involved in overseeing my book covers, which were designed by the art director of Random House.)

Most writers, myself included, want to be left alone. It is enough to write a book. For some, the very thought of promotion is a turnoff and they will have nothing to do with it. “Look at me! Buy my book!” Ugh. In my case, I am not shy; I am highly social. I like interacting with people and I will approach who I need to. I am proactive and will (try to) do what it takes to see to it that my books get in the hands of readers.

It's my understanding traditional publishers do not do promotion; they expect their authors to do it. I think any writer who wants readers to read their book/s will have to promote them themselves, however they can: use social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.), send press releases, seek reviews, ask for ratings, approach book clubs, accept invitations, submit for awards, do book readings. I’ve done it all, and I will basically go anywhere I’m invited. And of course, there is a lot of follow up, getting back to people who don’t get back to you (something I really don’t like to do). Since my memoir came out, I’ve been following this dictum: “You’re a writer and you published a book. Now you’re an author and you must promote it.” And quite honestly, promoting one’s book—and there will be missteps—is practically a full-time job.

It is only recently that I figured out there is a difference between promotion and marketing. I do no marketing. I do not involve myself with giveaways, special offers, pre-orders, or any of that. I am not saying anything is wrong with it, I just don’t want to bother. It seems to me there is a lot to do with timing, pricing, and calculating.

I’ve said it before, and I will say it again: I have no interest in making money from my books. Selling books will do little to enhance my fortunes. But I am very interested, indeed dedicated to and invested in, people reading my books. I think they are good books.

What is an average writing day like for you?

I wake up (6:00–7:00 a.m.). Get dressed and go for a swim (local pool). Have breakfast (oatmeal, boring!) and a cup of black tea. (Yes, I live in the middle of green tea country.) I go to my desk, where I write at an iMac. Either I am writing something, or I am doing some aspect of promoting my books, which I think is unending.

I back away from the computer around 5:00 and will not look at anything online until the following day. My perfect day ends with a good meal, cooked by me or my husband, and a glass or two of wine. While we clean up, I might sing along with Roberta Flack, or dance to any good music Billy puts on. In all my years here, it’s just in the past few months that I’ve watched Japanese television programs, the historical dramas, which I’ve been enjoying while I knit. It’s lights out for me by 10:30. I’ve never written one word at night.

Interview via email May 2023

Compiled by Kathleen Morikawa and Lynne E. Riggs

for publication on the SWET website © 2023 SWET