February 6, 2019

Jared Lubarsky: What Puts the Spring in My Step

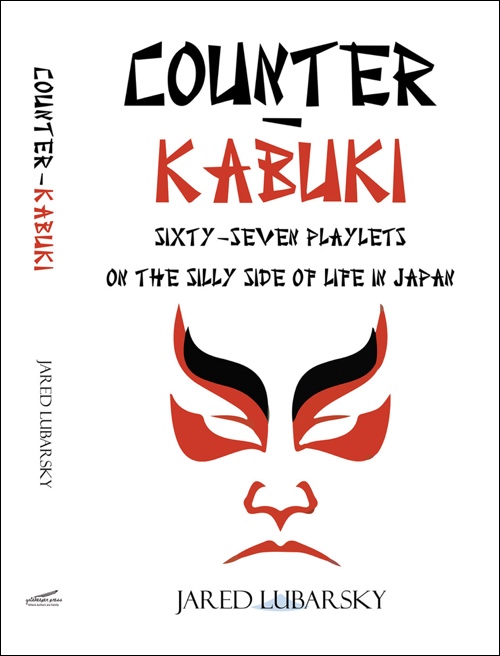

Author of the recently published Counter-Kabuki: Sixty-Seven Playlets on the Silly Side of Life in Japan, Jared Lubarsky has been a full-time resident of Barcelona, Spain, since 2005. He was raised in Massachusetts and did his undergraduate and graduate studies in Pennsylvania, where he also had his first teaching job, at Haverford College. He arrived in Tokyo in 1976 to work as in-house editor at the Japan Foundation, and began to write freelance for a wide range of newspapers and journals, travel publications, and inflight magazines here and abroad. Jared was a founding member of SWET, joining our planning meetings and speaking on panels for events three times from 1984 to 1987. While gradually shifting his place of permanent residence from Japan to Barcelona, he taught literature and comparative culture at Josai International University in Chiba Prefecture, returning periodically as a visiting professor until 2018.

You have been making a living from your writing for several decades, but please tell us a little about how that got started, what good breaks you had, and what you have enjoyed most about your writing.

I came to Tokyo after a two-year appointment at Hirosaki National University, in the frozen far north, where I started to write sketches—for my own amusement—about the strange and quirky things that tended to happen to me there; when I moved to Tokyo, I took the sketches to the Mainichi Daily News, and somehow persuaded them to give me a weekly humor column. With that dubious credential I got my first assignment for a longer piece from Tom Chapman, editor in chief for Wings, then the Japan Airlines inflight magazine. Tom was a wonderful editor to work for, and pretty much gave me carte blanche for whatever story ideas I brought him. As I got more comfortable with the 1,500–2,500-word format and learned how to pitch proposals, my client list got longer, and I kept it with me when I moved from the Japan Foundation back into the academic world. Having a day job with a predictable steady income has a lot to recommend it, but by then I'd discovered that writing—humor, travel, cultures and their differences—was really what put the spring in my step.

You lived in Japan in a very interesting period (mid-1980s to early 2000s). What do you remember most fondly from that time? Who were some of the interesting people you met?

From the mid-1980s until I went back into university teaching full-time, I was writing mostly for Japanese publications or about Japan for publications abroad; easily the best thing about that work was the wonderful range of iconic figures I got to meet and talk with. For the National Portrait Gallery in Washington I did an exhibition catalog that involved a series of interviews with Hosokawa Morisada, then doyen of one Japan’s most distinguished daimyo families (his son was briefly prime minister). For the New York Times Magazine I did a portrait of figure skater Itoh Midori. For the Japanese edition of Playboy Magazine, I went to Sri Lanka to interview Arthur C. Clarke. For PHP I wrote a focus story on architect Isozaki Arata, and for Tokyo Journal another on sculptor Isamu Noguchi. The Japan Quarterly had me do a piece on celebrity newscaster Kume Hiroshi. For the National Geographic Traveler, I got to hang out with the yabusame archers at the annual Tōshōgū shrine festival in Nikkō, and for Winds with rakugoka, sumo wrestlers and PEN Club novelists. I was a cheerful non-specialist, all over the map; one day I woke up and said to myself: “Holy cow, I get to do all this interesting stuff—and they pay me for it!”

Starting in 1989, Fodor’s Travel Publications asked me to write/update the Tokyo, Yokohama, and Kamakura chapters of their Japan guide, and my focus shifted to travel writing—more and more of it abroad. I still had Fodor’s as a client when I moved from Japan to Spain in 2005, and until this past year I covered Barcelona and the Balearic Islands for them. Other assignments have taken me to the Douro port wine region in Portugal, Alsace, Germany’s Lake Constance, the hill towns of Umbria in Italy, Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, and—improbably, but a fount of great discoveries—Santa Lucia in the Caribbean. So little time, so many places yet to see.

Could you share something of your experience and thoughts as a “travel writer”?

Landing freelance travel article assignments has become vastly more difficult than it was when I started writing for that market. I had a fair amount of success with “package” proposals—that is, working with a photographer from the beginning, framing the pitch together and offering the client a pictures-and-text combination (caveat: photographers have their own work styles and imperatives—mainly they obsess about light—so be certain your package partner is someone you can spend a high-pressure week or more with, at close quarters, without going postal)—but nowadays editors are happy to buy generic photos from archive services and tend either to assign articles to in-house staff or to look for writers with some sort of celebrity name recognition. To have any chance of cracking that market, you first need to forget about the sort of see-this-do-that destination stories that have long since gone stale and find something quirky, off-the-beaten-track about your subject, something the casual traveler is unlikely to stumble on (even in a Google search) and allows you to frame the piece with your own personal experience of the place. Here’s a cut, for example, from one I did on the Duero region of Spain for the San Francisco Examiner, framing it as a sort of travel log:

1:45 p.m. Smooth passage from Cuellar to Tudela de Duero. The sun is out again. The Other Half climbs out of the car at a gas station, and goes inside to ask the way to Vega-Sicilia. Just at that moment, around the corner comes a flock of 70 or 80 sheep, cuts through the gas station, flows around the car on both sides—I’m surrounded! I’m in mutton up to my windshield wipers!—crosses the highway, browses its way up a hill, and disappears. The Other Half returns.

“Did you see that?”

“No. What?”

2:00 p.m. A sign points us off the road to Vega-Sicilia: we decide to trust it; the fields on either side, after all, are planted with vines. The cellars themselves aren't much to look at, but we get to try the Valbuena five-year-old, which puts the whole trip in a different perspective. We also get to talk with Sr. Jesus Anadon, who retired in January after 40 years as director of the winery. An inspired question: “Where do you recommend around here to eat?”

“The Casa Mauro, in Peñafiel.”

Peñafiel, according to the map, is 15 kilometers away. The Other Half and I have an understanding on these matters: neither of us would think twice about driving 15 kilometers out of the way for a restaurant recommended by somebody who has spent the last 40 years making world-class wine.

Editors differ on how far you can make the story about yourself; the pieces I’ve usually felt best about were the ones where I had the freest rein to play with the narrative voice.

That’s what travel books are all about, of course: they’re supposed to be first-person adventure stories, experiences most readers don’t really expect to have for themselves (Paul Theroux’s The Old Patagonian Express and Bill Bryson’s Notes from A Small Island are wonderful examples). I can’t say much about that end of the market, since I’ve never written for it, but I can make a couple of points about guidebooks. First, there’s hardly a place left on the planet that doesn’t already have a vade mecum, so guidebook publishers are most likely to be interested in updates—preferably by writers who live where they’re working. The temptation in assignments like that is to take shortcuts, which you need to school yourself against: you really do have to visit every place you write about, and verify all the relevant service information in person. Second, expect guidebook work to put a cramp in your style. Having to “capture the unique essence of Hotel X in 100 words or less” may pay the rent, lord knows, from time to time—but it’s no fun.

In a sense, travel writing is the opposite of investigative journalism: you get to meet people who love what they’re doing and are only too glad to talk to you about it. I’ve been lucky to land assignments from publications with high-end demographics, so I’ve had wonderful conversations with chefs and winemakers, artists and musicians and designers, artisans and antiquarians, innkeepers and entrepreneurs, gem miners and boat builders—shared moments in the lives of people who shape the character of the places I’m writing about. These are the contacts that make travel writing a delight.

So now you've been living in Barcelona for 15 years, and you and the Other Half are both expatriates there? What are the particular attractions as a place of residence for people like yourselves? Is it a place where you will both feel com fortable into advanced age?

fortable into advanced age?

Aptly enough, it was freelancing that moved us to Barcelona. In 1987 I was working with a photographer who suggested we try putting enough assignments together to make a trip to Barcelona worthwhile; we did, and I fell in love with it. A few months later I went back with my wife Masumi, this time on vacation; she felt the same way—and before our vacation was over, we had somehow contrived to buy a flat—signing the agreement of sale just days before it was announced that Barcelona would host the Olympics. Flash forward to 2005: a tenant had just moved out; that seemed opportune, so I resigned my teaching job out in Chiba, and we moved here full-time. It took five years for us to get our long-term resident cards (the equivalent of eijū-ken), but the process was relatively painless.

Our home is in Sarriá, a neighborhood that was an independent village until sometime in the 1920s, when the city grew out and absorbed it. On both sides now are upscale residential areas of multistory apartment buildings with concierges, interior gardens with pools, leafy avenues—the whole catastrophe. Sandwiched in between, Sarriá is still much the village where the late 19th-century industrial bourgeoisie built their humungous family homes to escape the air downtown: cobblestone streets, tenth-century church, 100-year-old covered market, Moderniste mansions with sgraffito facades and stained glass and wrought-iron balconies. There are three populations here: the old-timers, who speak only Catalan among themselves and talk of going “down to Barcelona” to shop; the creative cohort (artists, architects, designers, people in PR and publishing), who discovered Sarriá about the same time we did; and the double-income yuppie starter families, with their BMW double-wide baby buggies and Ecuadorian maids. There’s nothing you can imagine needing in the course of the day, from the dry cleaner to the florist, from the National Health system primary care clinic to the bar that serves drop-dead Tex-Mex bacon chili cheeseburgers, that’s more than a few steps from our flat—as is the Metro, which takes us downtown in ten minutes. We’re obscenely happy here, and hardly a day goes by when we don’t congratulate ourselves, one way or another, about winding up as retirees in this wonderful part of this wonderful city.

Your Counter-Kabuki book collects stories, your preface says, that "cheekily" depict the Japanese penchant for exceptionalism, with humorous portrayals of "some of the foibles that have tickled me most" in dialogue form. Are you working on a sequel?

Counter-Kabuki is likely my last published word on the ineffable goofiness of Japan. I still write sketches in that vein whenever one of the online newspapers yields something especially ripe, but essentially for my own pleasure and for my email circle; I doubt if I’ll be able to put another book’s worth of them together before I croak. (Counter-Kabuki is available from Amazon, and in ebook format from Rakuten Kobo.)

Compiled by Lynne E. Riggs

Published for the SWET website, February 3, 2019