November 30, 2017

Michihiro Hirai’s Technical and Business English Expertise Marathon

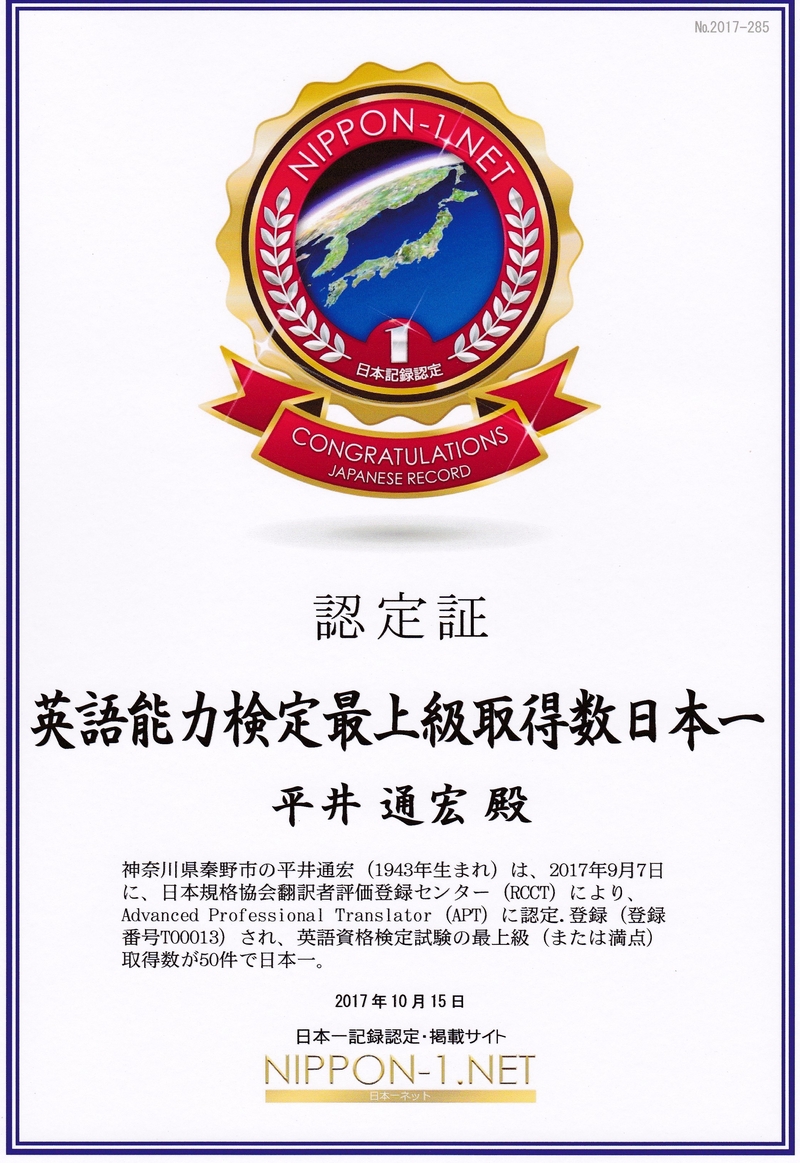

Long-time SWET member Michihiro Hirai works with publishers and language-related organizations as a translator, writer, teacher of technical and business English, and consultant. He is also a collector of English-language qualifications: he recently let us know that he had passed his goal of earning 50 of them and is eager for more. Taking this opportunity to celebrate Hirai’s achievement with him, SWET had him share the story of his career and what he has learned over the years from his test-taking marathon.

The list is just amazing, Hirai-san! When did you start this?!

The list is just amazing, Hirai-san! When did you start this?!

I started this marathon in 1973, when I came back from studying abroad at the University of Pennsylvania, but initially I was not so crazy about it. At the time I was working as an engineer designing mainframe computers for Hitachi in Kanagawa. But in 1992, when I turned 49, I felt I had gone as far as I could in the company as an engineer, and decided to make a career switch. I had been given many language-related assignments because of my background, so I thought of doing something with that experience, and that was when I began to work seriously on getting as many English qualifications as possible. I’ve acquired most of them (47 out of 50) over the 25 years since then. By the time I retired from the company in June 2002 I had amassed 30 “crowns,” which means I got the other 20 over the past 15 years, since shifting careers and founding Hirai Language Services.

So you gained your basic facility in English while studying in the United States, and then kept it up by studying and reading? Did your work at Hitachi involve working with overseas businessmen and companies?

Yes, luckily, very much so. From 1976 to 1998 I was involved in exporting our mainframe computers, which kept me in English-speaking environments most of the time. I coordinated technical and sometimes business communication with our American and European counterparts, including translation, meetings, and presentations. I made more than 100 overseas business trips, which is unusual for a design engineer, visiting 40 countries and spending altogether more than three years abroad, not counting the year I was studying in Pennsylvania. So I was able to capitalize on that extensive experience in launching my second career.

Which of the 50 qualifications were the most challenging? Did they require special study or cramming, or did you find that your experience allowed you to perform well without much preparation?

Language reflects all aspects of human thought and activity, and hence there are countless approaches to, and forms of, language tests as a means of assessing communication skills, depending on the purpose, domain, and other factors. At a presentation at the JALT Hokkaido Conference on October 2, 2016, I categorized the major English tests administered in Japan in several genres, including general (EGP), academic (EAP), and purpose-specific (ESP). For more details see my recent paper, “A General Overview of English Tests Administered in Japan,” Shiken: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter 21:1 (June 2017), pp.12–22, http://teval.jalt.org/node/71.

The style and purpose of English tests vary significantly from genre to genre. Of all the general-purpose English tests I have taken, I rate the Cambridge Main Suite CPE (Grade A) as the toughest and most thorough, and hence the best. Academic tests have recently been growing in number, and the tests, as well as the test-takers, tend to be relatively young. TOEFL® iBT® is by far the most challenging, especially for Japanese. Purpose-specific tests include those in business English such as Cambridge’s BULATS, technical writing, such as the Waseda-Michigan Technical English Proficiency (TEP) Test and Kogyo Eiken, various Tests of Professional English Communication (TOPEC), and translation or interpretation. Purpose-specific tests are designed to evaluate the use of English in actual work situations and therefore can be very challenging, especially in that they require a certain level of familiarity with the field. Of translation tests, I would rate the Hon’yaku Kentei offered by the Japan Translation Federation (JTF) as one of the toughest and the best.

For general English tests, I prepared mainly by focusing on vocabulary (including idioms and collocations), as my knowledge of grammar was already sufficient. For technical writing and translation tests, I attended a couple of ad hoc courses on these subjects. For every test my experience at Hitachi as an internationally minded engineer has stood me in good stead, particularly inasmuch as I have always been attentive to the actual usage of English on the job.

For some of these tests, did you need to pay attention to particular styles of spelling/grammar/punctuation (e.g., American vs. British) or to kinds of technical vocabulary?

For some of these tests, did you need to pay attention to particular styles of spelling/grammar/punctuation (e.g., American vs. British) or to kinds of technical vocabulary?

I didn’t worry too much about spelling and punctuation, because most language tests (except those targeted at young learners) are lenient with such errors. I’ve been largely able to avoid grammar errors because being a design engineer requires you to pay attention to details, and so I have always been meticulous about grammar to a hair-splitting degree. As for translation tests, which are generally offered field by field, I have had the advantage of being a computer engineer equipped with a relatively rich vocabulary in information and communication technology. Most translation tests these days are open book, so you don’t need to memorize all the terms, but some familiarity with the field is still a big advantage in that you don’t have to keep consulting dictionaries or the Web while you are pressed for time. (Photo: Courtesy of Town News-sha, Co., Ltd.)

Have you felt the pressure to be able to show such qualifications from clients? Or did you pursue them mostly as a personal objective?

Initially I expected, rather naïvely, that having many qualifications would help me quote higher-than-average translation rates. But for some reason, most translation agencies do not seem to recognize or value language qualifications. Perhaps they have had too many bad experiences with people who boast of Eiken 1st grade or TOEIC® 900 yet cannot write ordinary business emails or translate technical documents or business memos. So I have pursued this endeavor mainly as an act of self-realization or ego-realization, however you may view it.

Only recently, after I earned 40 or so qualifications, including some of the heavyweight translation tests, have some translation agencies and clients started giving me some credit for them by exempting me from onerous trials.

Outside the field of translation, my language qualifications did help me to obtain a decent job at a private university as a technical English teacher. There is a scarcity of people with dual backgrounds (in technology and English), and as it turns out, teaching and translation go hand in hand quite neatly.

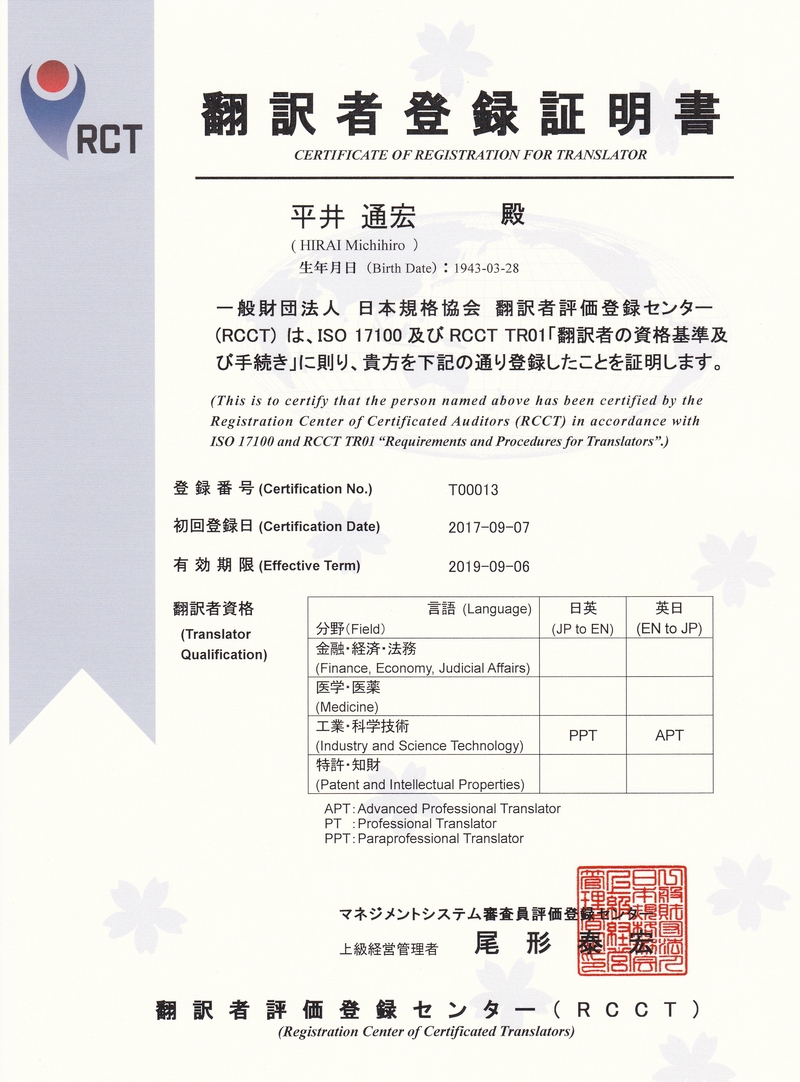

Your website notes that you are certified by the American Translators Association (ATA) and Registration Center of Certificated Translators (RCCT). Sounds truly powerful! The RCCT registration is your “50th crown”! What is the RCCT registration, by the way? Is this something we should all know more about?

Your website notes that you are certified by the American Translators Association (ATA) and Registration Center of Certificated Translators (RCCT). Sounds truly powerful! The RCCT registration is your “50th crown”! What is the RCCT registration, by the way? Is this something we should all know more about?

RCCT is a new official translator recognition scheme launched in Japan in April 2017. It implements the ISO 17100 standard for endorsing translator quality through the Japanese Standards Association (日本規格協会: JSA) under the (indirect) auspices of the Japanese government. As one of the JSA’s branch organizations, the RCCT certifies and registers qualified translators at three levels: Advanced Professional Translator (APT), Professional Translator (PT), and Para-professional Translator (PPT).

The RCCT initiative is quite new but has already attracted a lot of attention in the translator community. It is actually an offshoot of ISO 17100:2015 Translation services—Requirements for translation services, which lays down standards and guidelines for ensuring the quality of translation and interpretation services worldwide over the entire spectrum from project management to quality assurance to certification of translators and translator qualification tests (this last one seems to be only in Japan at the moment).

The JSA started to certify translation agencies under this initiative a couple of years ago. Dozens of companies have already been certified, and the qualification is expected to carry considerable weight in helping them win potential customers’ trust, in the same way that ISO 9001 (product quality) and ISO 14000 (environmental friendliness) have done for industry as a whole.

The certification framework for individual translators is still young and may need some break-in tweaks. The requirements for the two upper levels (APT and PT) seem to pose a major hurdle for many translators in Japan, who have tended to avoid translation tests (partly because most translation agencies do not trust those tests in the first place). I would say a lot of translators are bewildered by this new scheme and are in a way secretly hoping that it will not take root—that if the majority of translators ignore it, it will eventually wither and go away. The JSA is apparently paying attention to these reactions and seems open to reaching a mutually acceptable common ground; it certainly does not want to turn translators away from the framework by setting the bar too high. For example, it has just recently amended the requirements for APT and PT to make it easier for in-house translators to be certified.

At any rate, I personally believe that this new scheme will take root sooner or later, because Japanese generally love and value rules, and that it will come to affect most translators—especially those working in technical fields (though not literary translators)—and, I would say, non-Japanese as well as Japanese. The Japan Translation Federation has shown a keen interest in it and has taken it up a number of times in its seminars and journals.

For details on RCCT, see the organization’s website (https://www.jsa.or.jp/jrca/jrca_rcct/). For a quick overview of ISO 17100, see http://shinsaweb.jsa.or.jp/MS/Service/ISO17100, or download the full text of the standard for a fee (about JPY15,000) from the JSA web store.

RCCT registration sounds like something that will become increasingly important in beating the competition as a translator in Japan. How do you see that?

RCCT registration sounds like something that will become increasingly important in beating the competition as a translator in Japan. How do you see that?

I think RCCT is part of the recent pervasive international effort to bring “global standards” into most aspects of our lives, including the economy and industry, which is what ISO is all about. It is a welcome move in that it puts many individual and local business practices into alignment with common standards, as I briefly mentioned above in citing ISO 9001 and ISO 14000.

ISO 17100 is especially important in Japan, where practically no common frameworks for translation and interpretation services have existed, let alone common yardsticks for measuring their quality. This is primarily because of the chronic shortage of competent language specialists capable of properly assessing translation quality, both at agencies and on the staff of their clients. The result has been an undue emphasis on low price and speed, inevitably sacrificing quality, which in turn undermines the motivation of competent translators. In my mind, such a situation, though unfortunately widespread, would be unthinkable and unacceptable elsewhere, for example in the manufacturing industry. Where there is no appreciation of quality, there can be no good products. Likewise, where there is no competition, there is no progress.

In this context, I see the RCCT initiative, along with ISO 17100, as a significant first step toward the normalization and modernization of the Japanese translation industry. The RCCT certifies agencies to ensure they are properly managing translation processes; its certification of individual translators, meanwhile, endorses their skills and quality and could bring about healthy competition.

From your experience in having been certified under the RCCT, what kind of knowledge is tested? English ability or procedural know-how? Is it aimed basically at standard business or general subject matter?

RCCT certification is awarded based on translation skills, academic credentials, and experience as a translator. As proof of translation skills you need either a first- or second-grade certificate from one of two RCCT-recognized English qualification tests (JTF Hon’yaku Kentei or the Nippon Intellectual Property Translation Association [NIPTA] Intellectual Property Translation Examination). Experience is basically measured in terms of the amount of translation (in number of words or characters) done over the past. Requirements in this category depend on your academic credentials: no occupational translation experience is needed if you hold a university degree in translation, a minimum of two years’ worth if you have a university degree in another field, and a minimum of five years’ worth if you have not completed a university education. Of the three different levels of certification, PPT is given to those who meet either the testing or the education/experience requirement, PT to those who meet the education/experience requirement and also hold a second-grade testing certificate, and the highest, APT, to those who meet the education/experience requirement and hold a first-grade testing certificate. The application procedure manual RCCT TR01, which can be downloaded free of charge from the RCCT website, provides the details.

As this shows, RCCT involves no direct test of skills, but instead relies on certifications issued by other parties that are recognized by the RCCT. As evidence of your experience as a translator, you need to compile data about your past work and have your clients (including agencies) sign off on the number of words or characters of translation that you have done for them. You then submit the data to the RCCT.

Now that you have proved to yourself and others that you know what you are doing, is it easier to solve problems in your work or convince clients to listen to you? What sorts of rewards have you won from this qualification marathon?

Now that you have proved to yourself and others that you know what you are doing, is it easier to solve problems in your work or convince clients to listen to you? What sorts of rewards have you won from this qualification marathon?

My collection of English-language certifications has paid off mainly in teaching and consulting jobs. As I said, it gave me a significant advantage over the competition when I first tried to become a teacher of technical English. The title of professor, although non-tenured (tokunin or “special appointment”), then helped me publish a couple of books on technical English, which in turn attracted some interest from other publishers and language institutions. Also, after I became known as an English test maniac, I was employed by Eiken as a test consultant for more than 10 years.

As I mentioned earlier, high-level language qualifications, even in translation, have been cutting practically no ice in Japan, but with the introduction of the new translator certification system, I hope things will change for the better for competent translators.

Language qualifications are important, but what other abilities do you think have served you best in your business over the past 15 years?

Certainly my engineering background plays an important role in what I am now. It gives me credibility in technical and, to a lesser extent, business matters, which is conducive to teaching practical English, doing industrial translations, and getting papers and books published.

So what are you aiming for now?

Looking back, I realize it's been a 44-year marathon. Actually, I took another English test (Intellectual Property Translation 1st grade: English to Japanese) quite recently that required a different set of knowledge and skills from other translation tests; I’m not confident at all about the result. But I’m a bit hooked on taking these tests. Too bad only the very tough ones are left. Maybe the 60th will be my “holy grail.” As the saying goes, happiness is doing what you like and liking what you do, and that’s what I’m doing.