March 5, 2018

Simon Rowe: An Independent Author’s Journey

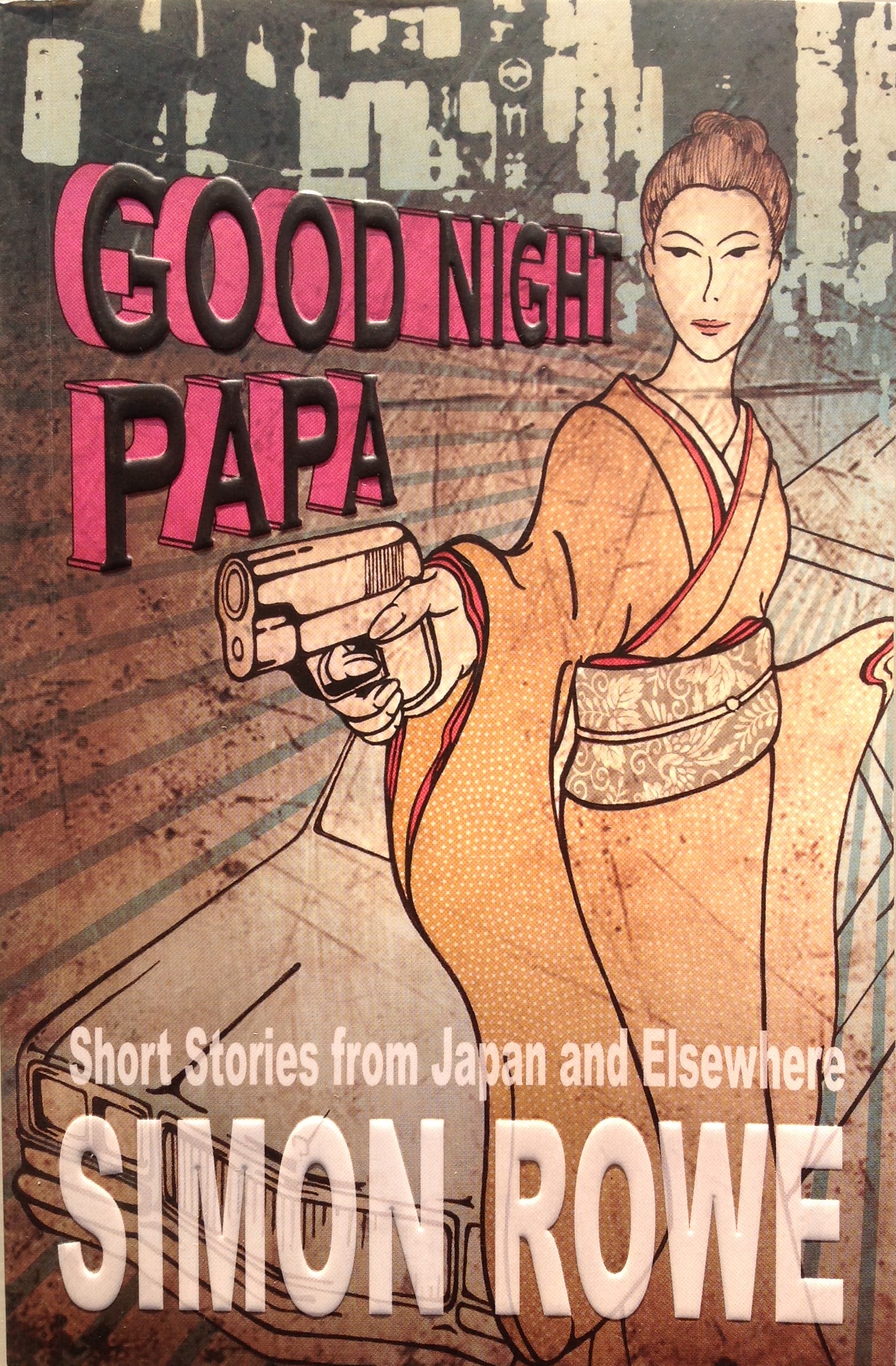

Simon Rowe is an independent writer who currently resides in the city of Himeji, situated in western Honshu and known for its splendidly preserved Edo-period castle. After 20 years of roving the world as a travel writer, he has turned to penning short fiction and screenplays. He has recently self-published a collection of short stories, Good Night Papa: Short Stories from Japan and Elsewhere. (Amazon.com link) SWET interviewed Rowe about his writing and self-publishing philosophy.

What was it like at the beginning of your attempt to self-publish and distribute your first book of stories?

It was like that moment before a long trip, when you survey the bed covered with every item you want to pack, but know you can’t. Self-publishing is the “backpacking” of the publishing world: you go it alone with little baggage and a lot of budget considerations. It’s a daunting prospect, but an empowering one too, because it puts total control of the process in your hands. I chose a print run over an e-book format, and despite this requiring a greater up-front financial commitment, I’m glad I did so. Some writers choose to do it the other way around, but in my mind a book in hand is cold hard evidence of your determination and commitment to see your writing through to the very end. It also gives you something to stand behind when you approach booksellers—literally!

My initial print run was a thousand books. My sister, who publishes children’s books through her Australian small press Atlas Jones & Co., connected me with a publishing broker (Imago Australia), who then managed the process, from receipt of pdf files, cover art, and embossing to printing and delivery of the books. The entire order was executed and shipped from Hong Kong to my door in less than one month.

The single biggest task of self-publishing (after writing) is marketing. How to attract readers? I experimented with Facebook, Instagram and Twitter to good effect—friends, relatives and acquaintances are very supportive and their initial purchases can be real confidence boosters. Spreading the word across the ether, however, is not enough. If you have a physical copy of your book, you have to get physical, which means cold-calling on bookstore managers, renting a local flea market stall, approaching souvenir kiosks, as well as managers of bars, restaurants, and cafés—anywhere where English-language readers might visit or congregate. While it hasn’t been hugely financially rewarding, I would have to say that the experience of meeting people, growing networks, acquiring Japanese business language skills and marketing knowledge, not to mention seeing my book on shelves in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and Paris, and in the hands of readers around the world, has left me spiritually richer.

Who did you think would be most likely to buy the book and how could you reach them?

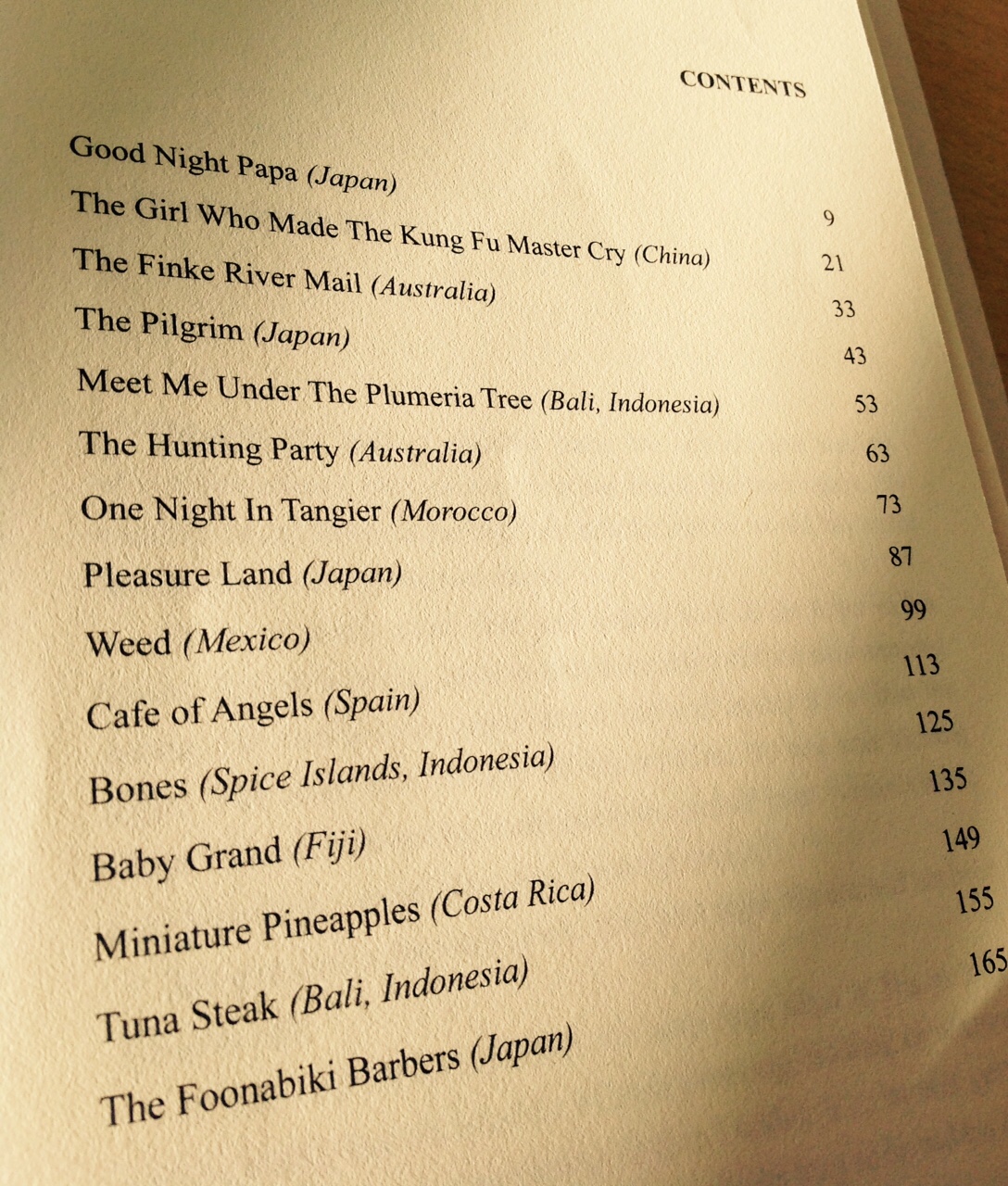

Time-poor, travel-hungry readers! I believe short fiction is the genre of our times. Short tales, set in exotic locales with hapless and helpless characters who by wit or resolve overcome their problems, are what I enjoy writing most. I drew inspiration from my own travel journals from twenty years ago, and used imagination and life experience to create the realistic situations through which my characters move. The Good Night Papa collection includes a tale about a recovering alcoholic mail pilot who survives a plane crash in the Australian desert with a bottle of gin on board, a snobbish European widow who must ask local cannery workers to carry a grand piano to her hilltop home in Fiji, and a half-Japanese fugitive who disguises himself as a Buddhist pilgrim only to find that his fate rests in the hands of a novice monk on Shikoku island.

Did you try selling through bookstores?

Yes. My approach was two-pronged: target booksellers inside and outside Japan. To independent book retailers in Australia and New Zealand, I pitched myself as a “homegrown” writer. I contacted stores which support independent writers and e-mailed them a book backgrounder (including price, ISBN, etc.) and several images. Responses were initially low, perhaps due to the timing of my pitch, which was during the summer holidays. However, a handful of bookstores across the two countries did reply and offered to stock. A year later, all of them are on their third and fourth orders.

Booksellers in Japan required more footwork (“hard yards” in the Australian vernacular), which entailed packing a satchel full of sample copies and trooping off to Osaka and Tokyo to cold-call buying managers of the big bookstores like Maruzen, Junkudo, and Tsutaya. Meeting a manager face to face is the best way to get your voice heard above all the new-release noise filling their mailboxes daily. Also, being able to place a book in their hands shows that you are determined and in earnest; I think merchandising managers respect that.

Luck—and leveraging luck—plays a big part in self-publishing success too. In my case, the regional Kobe Shimbun newspaper ran a weekend story about Good Night Papa in spring 2017. It cited the lead story of my collection, also titled “Good Night Papa,” a mystery-suspense tale set in Himeji city. This generated a lot interest from local readers, which I was then able to leverage in a meeting with the regional manager of national giant Kinokuniya Books. He decided to trial the book in his Himeji and Kobe bookstores, wedged between the Mishima and Murakami English translations—not such a bad place for a relative “nobody.”

Did you mobilize social media to market your book? What were some of the techniques you adopted to get the word out?

Did you mobilize social media to market your book? What were some of the techniques you adopted to get the word out?

An independent writer cannot afford to ignore social media as a marketing tool. The time to start using it is now if you intend to self-publish. Loyal readerships take time and nurturing to grow. Facebook enabled me to build an audience over time (I shared blogs about my life in a Japanese neighborhood from my website www.mightytales.net/seaweed-salad-days) long before Good Night Papa was even conceptualized. Instagram is another of my favorites; it can be used to advertise a book visually—which I have done thanks to my globetrotting readers whose photographs of the book in exotic locations I continue to post.

So your strategies of distributing sample copies and following up with agents and bookstores paid off?

Very much so. A year on, after finessing and resending my initial pitches to bookstores outside Japan, new orders have resulted. I would put this down to a leaner, sharper pitch and timing these pitches for outside busy periods like Christmas and summer holidays. Giveaways and sample copies are also a good idea—I’m always happy to send one to a bookstore manager if the staff would like to get a “feel” for it. Giving back to the community is good too; copies of Good Night Papa now sit in Himeji’s municipal library and the Himeji City Museum of Literature.

Did you edit the stories in Good Night Papa entirely yourself? Are the versions in the book the result of a process of revision, for example, reflecting the “road tests” of submitting them to screenplay contests?

When is a story ever truly finished? This is a question most writers find difficult to answer. I edited all fifteen of the stories in my collection to the best of my ability, then hired a professional editor to have them line edited. I was happy to step back and let fresh eyes see new ways of strengthening the stories and improving expression and clarity. Once these were made, I felt ready to move to the publishing stage. My editor, whom I found through Tablo, an Australian-based digital platform for new writers, was very easygoing, encouraging, and extremely insightful. Hailing from the same city of Melbourne—which incidentally, is a UNESCO City of Literature—meant we were thinking on the same frequency. I opted for the Oxford style of editing and punctuation.

Would you be able to share a specific example of how you “sliced and diced” to pare down a story to the short-story genre? Say with a representative paragraph? Or an ending paragraph?

In his book On Writing (2010), Stephen King, love him or loathe him, compares writing a story to uncovering a dinosaur fossil. This resonates with me because, although I start with a plan, a list of detailed characters and a rough scenario, I have no idea what shape the story will take until those bones appear. Work on my lead story, “Good Night Papa,” actually began with one big bone—the title. It happened the day I glimpsed a delivery truck in my neighborhood with “Goodnight Baby Express” printed on its door. I started writing that night and finished “Good Night Papa” a week later. It’s the tale of a retired Japanese taxi driver who takes a job driving call girls, only to receive an unexpected gift from a mysterious passenger. The following excerpt survived countless edits to make it onto the printed page:

Now that he worked for the agency, however, things were different. His passengers were all young women. Most were vain, simple-minded things. They knew nothing of the world—let alone Elvis. But they loved him, and it was they who had given him the name “Papa.” In turn, he took good care of them, treated them like ladies. When an engagement had ended and he had driven them home, he would sign off with “Goodnight baby.” It was his trademark, and it made them giggle.

Being in complete control of your own publication sounds very appealing. Have you found any downsides of that independence?

None whatsoever. But I would add that the amount of success a writer can enjoy by self-publishing is relative to the quality of their writing and the time and energy they are prepared to spend getting it into readers’ hands.

What do you think SWET can do for you? What would you like to do via SWET?

I would very much like to read about other members adventures in writing, editing, and translating. After lighthouse keeping, writing is one of the loneliest professions. It would be nice to have some company.

See also “Simon Rowe: Adventures in Self-Publishing,” an extensive interview with Rowe on Tablo (tablo.io), an Australian-based platform for writers.