May 13, 2020

From Behind Cloistered Walls: A Tale of Two Translations

Lynne E. Riggs

____________________________________________________________________

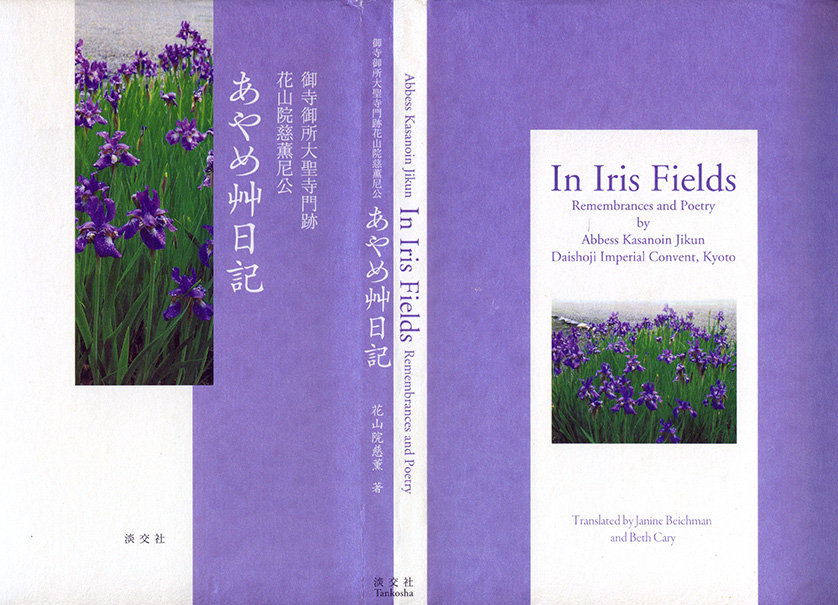

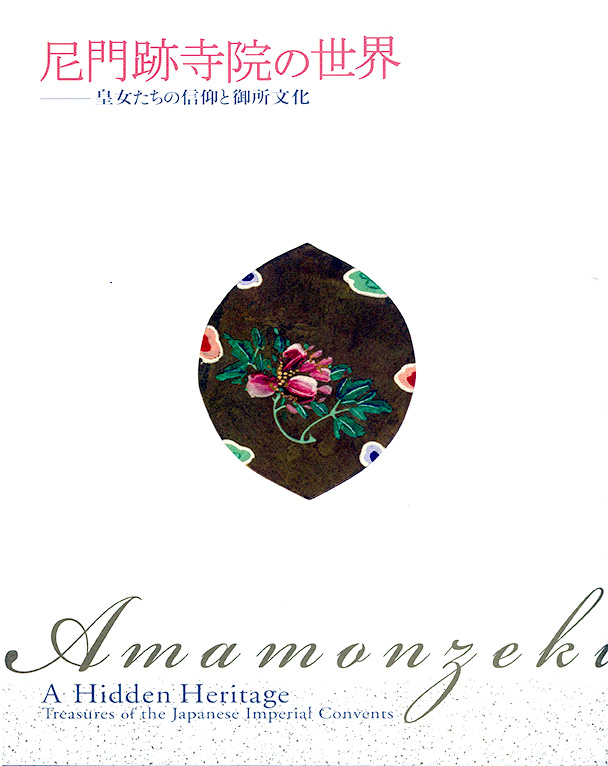

In February 2009, In Iris Fields: Remembrances and Poetry by Abbess Kasanoin Jikun, edited by Barbara Ruch and Katsura Michiyo, was published by Tankōsha (Kyoto). The book’s prose was translated by Beth Cary and its numerous poems by Janine Beichman. In early April, Amamonzeki—A Hidden Heritage: Treasures of the Japanese Imperial Convents, edited by Patricia Fister and Monica Bethe, was published as the catalog for an exhibit co-organized by the Medieval Japanese Studies Institute (Kyoto), the Tokyo University of the Arts, and Sankei Shimbun Sha, held April 14–June 14 at the Tokyo University of the Arts. On May 23, taking advantage of the presence in Tokyo of several of the principal people involved in both projects, SWET held a special tour of the exhibit followed by a talk featuring Cary and Beichman and dinner at a restaurant in Ueno Park.

______________________________________________________________________

Two bilingual book projects were completed in spring 2009, both recording life in the amamonzeki, or imperial convents of Kyoto and Nara, whose histories go back to the seventh century. Translating from the relatively small world of Japanese culture, society, politics, or any other milieu into the wider world of that field in English always demands some degree of specialized knowledge, but when the subject is a world little known even within Japan, the wordsmithery of both translator and scholar is tested to the utmost. The translators of the book In Iris Fields, by Abbess Kasanoin (1910-2006), and the catalog for the “Amamonzeki: A Hidden Heritage” exhibit held at the Tokyo University of the Arts went valiantly forth to meet this challenge Both projects are the result of translation, editorial, copyediting, writing, design, and layout work made possible by close collaboration among scholar-authors and professionals. They exemplify useful practices in team and collaborative translation, editing, copyediting, citation style, and text layout for presenting rich content in a way that is accessible for both general and specialist readers. The mediation of writing style and tone for the prose and poetry by the Abbess Kasanoin in the book and for the analyses of Japanese and non-Japanese scholars in the art catalog involved special considerations and balances. Both volumes embody somewhat out-of-the-ordinary ambitions for the physical book with back-stories that wordsmiths will appreciate. This account is an unabashedly wordsmith-oriented view of the two projects written in the hope that the experiences will yield hints for others engaged in Japanese-English bilingual publishing.

A Life’s Story in Prose and Poetry

In Iris Fields and Amamonzeki: A Hidden Heritage are both essentially book projects initiated by scholars who were able to bring in professionals to help with the translation, editing, copyediting, proofreading, and layout and production work involved. Given the nature of the content, however, ultimately the scholars had to do a lot of the wordsmithing (rewriting, editing, copyediting, and proofreading)—work that might have been left to professionals—while the professionals often had to perform tasks that took them deep into scholarly territory (checking name readings and facts, elaborating arcane references, and giving appropriate glosses). Fortunately, this necessity was understood from the outset, so good working relationships were maintained among those involved and high standards bound them all together. Indeed, both books are landmark works in a long line of valuable cultural publishing projects that we wish we could see more of these days, despite the costs and travails involved. Even if the annual report for a large corporation might generate more money, a professional is likely to be more proud of autobiographical works or art catalogs of this kind.

The catalytic figure behind both projects, and particularly In Iris Fields, is Barbara Ruch, a veteran scholar specializing in Japanese literature and cultural history, now professor emerita at Columbia University, who frequents Japan for various projects for the advancement of scholarship and the arts. Ruch is founder of the Donald Keene Center (in 1986) and long before that the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies (in 1968), both at Columbia University. The Institute is devoted to bringing to light the cultural history passed down by the princess-nuns of the imperial convents, and under Ruch’s directorship has backed numerous endeavors, including the work of a group of researchers under the Imperial Buddhist Convent Research and Restoration project which began in 1993, and included significant art and architectural restoration projects; and publications and exhibitions to bring public attention to what Ruch calls “Japan’s most fragile cultural treasure.” In 2003, Daishōji temple generously made its priory available to the Institute as an office. It was from this Kyoto office that the two book projects discussed here were coordinated. Ruch writes in the art catalog (p. 15) of her hope that

this exhibition will amaze and activate the viewers and thereby win for these convents new allies and supporters, inspired by the lives of the eminent Japanese women re-introduced here to our consciousness. These were the Japanese women leaders of past religious and cultural history—women who believed they could make a difference in the peace and safety of their nation and in their own spiritual and cultural lives, and they did.

We can get a sense of the power of Ruch’s determination to achieve this goal by looking at the list of supporters, which includes Her Highness Empress Michiko of Japan, the Foundation for Cultural Heritage and Art Research and the International Foundation for Arts and Culture in Tokyo, and the World Monuments Fund in New York, the Sankei Shimbun, Tokyo University of the Arts, not to mention the scholars, museum curators, translators, editors, and other collaborators who poured their efforts into these and other projects of the Institute; some for pay, others for different rewards.

The Prose of an Abbess: Intertwined Styles

Veteran translators are keenly aware of how almost every life experience they have is bound to serve as useful reference in their work. For San Francisco-based Beth Cary, in addition to a record of numerous non-fiction translations (including Sensō: The Japanese Remember the Pacific War [Sensō: Chi to namida de tsuzutta shōgen edited by Asahi Newspaper] edited by Frank Gibney; An Ecological View of History: Japanese Civilization in the World Context [Bunmei no Seitaishikan] by Tadao Umesao), it turned out to be a childhood lived in Kyoto that led editor Barbara Ruch to search her out for the translation of In Iris Fields. Cary was invited in June 2006 to meet the author at her convent, Daishōji in Kyoto. Cary recalled how the abbess told her, “Yes, I knew your father” [Otis Cary] as they recalled 1950s Kyoto and the landmarks they both remembered well, which also figure in the text. “I recall so often walking by the long white external property walls of Daishōji Imperial Convent,” writes Cary in her translator’s message in the book, “banded with the five narrow horizontal stripes (suji bei) marking it, like the Kyoto Imperial Palace itself, as connected to the Imperial household.” This turned out to be the very path she crisscrossed two or three times a week to visit her best childhood friend who lived across the street from the temple. As far as imagining the physical environment of the city in which her author lived, Cary enjoyed the opportunity to revisit the landscapes of her childhood. When the abbess wrote of her memory of returning from an elegant “mushroom gathering” outing at the imperial Shūgakuin villa in 1919, Cary could envision the very path taken through the city by the carriage: “hanayakana aki no yūhi o abitsutsu Yamabana Kaidō kara Kamogawa no tsutsumi o tōtte kita” (“. . . coming back down Yamabana Road along the Kamo River embankment bathed in the gorgeous light of the autumn setting sun,” J. p. 51; E. p. 45). The chance to meet her author, hear her voice, and observe her gestures only two weeks, as it turned out, before the abbess’s death, proved invaluable as Cary later labored to render the distinctive tone of the essays into English.

Cary is among a number of experienced translators who grew up bilingual in Japan, strengthened their language and writing skills with a good liberal arts education in the Anglophone world, and then gained experience with diverse non-technical material. At Wellesley College, Cary says she took Chinese because there was no Japanese at the time and put together a major in Asian Studies consisting of history, art history, political science, and other subjects in the curriculum. She also pursued graduate study at Sophia University, focusing on Japan’s international relations. With this rich liberal arts education, she has built a successful career as an interpreter and translator. She is accustomed to adding to her broad knowledge gained in university with quick, in-depth research on the specific topics of each job at hand. This skill was especially needed for the essays of Abbess Kasanoin, who was part of Japan’s social elite (cloistered as it might have been) and lived through tumultuous decades of Japan’s twentieth century. Cary found that “each essay turned out to be a different history lesson, with prose flowing from recollections of some historical event as if it were just yesterday, to current events, to personal reflections—all of them intertwined.” Indeed, the text casually drops references to annual rituals hardly known outside of Kyoto like the jūsan mairi (thirteenth-year rite), specifically Kyoto customs like Minazuki harai (June purification rites), historical events like the bakugun seibatsu (suppression of the shogunal forces after the Meiji restoration) and visits to Kyoto by Emperor Meiji, or terse-in-Japanese mentions of famous landscapes like “Hagoromo no matsu ya Senbon Matsubara, Okitsu Seikenji” (J. p. 82) that need some elaboration to get the meaning across in English (“the Hagoromo pine tree where the legend says a celestial robe descended from the heavens; Senbon Matsubara, the forest of a thousand pines; and the Zen temple Seikenji in Okitsu with its spectacular view,” E. p. 78).

Given the ambition of translation to reach a much wider readership than did the original essays in In Iris Fields (published in a tea ceremony school journal), collaboration is an essential element, especially for the completion of a work of non-fiction. Conscientious as the efforts of a veteran professional translator may be, often the client/scholar side has preferred wordings or interventions to suggest, and can supply background or amplification needed for that wider readership. Barbara Ruch, who had known the abbess for many years and is a specialist on the culture of the imperial convents, often edited heavily in hopes of finding words as close as possible to capturing the voice of the author.

One of the major hurdles in translating an author trained in a temple with connections to the imperial court was the appearance now and then of expressions in gosho kotoba, the special court language that was spoken by generations of abbesses at the convent and continues to be part of the vocabulary of convent life. The style of Abbess Kasanoin’s writing even within a single essay ranges from literary prose, to gosho kotoba, to contemporary colloquial language. The abbess’s courtly language uses euphemistic terms such as the phrase “okakure asobashita” which refers to the death of an imperial family member or an aristocrat (J. p. 62; E. p. 55), while the more usual polite term “onakunari ni narareta,” is used for Professor Yamamoto, her instructor in The Tale of Genji (J. p. 133; E. p. 126). Many of the gosho kotoba are terms for foods and clothing, such as kakigachin for kakimochi, or rice cakes; oshitaji for shōyu, or soy sauce (J. pp. 32–33; E. pp. 26–27).

Another complexity the translator (and editor) had to manage is the way individual persons have various names, particularly women in the court-connected world of the amamonzeki. Cary recalls the example of Lady Yanagiwara Naruko (whose name is written 愛子, but not read “Aiko”). One of Emperor Meiji’s concubines and the birth mother of Emperor Taishō, she was also known as Nii no Tsubone (lit., second ranking lady-in-waiting) or as Lady Sawarabi (lit., Lady Spring Fern). A translator must be alert for the person who might be mentioned by different names in different contexts and render her identifiably in English (the translation prefers “Lady Yanagiwara”).

The text is filled with references to noh plays, ancient poems, and other works of literature. Partly because of Abbess Kasanoin’s membership in a group studying The Tale of Genji, her writing often alludes to poetry, characters, and story in the Tale. When the author says, “everyone knows . . . such-and-such a passage of the Tale” (Genji monogatari ni tōjō suru Aoi no Ue to Rokujō no Miyasudokoro to ga, Aoi matsuri o minto monoi-guruma no basho-arasoi o shita hanashi wa dare demo ga shiru tokodo de, J. p. 47; E. p. 42), the translator must be sure to be among them. As many professional translators find, when a Japanese author makes reference to the Tale, available translations rarely fit the context, but having the various Tale of Genji translations at hand can be a useful starting place for creating an original wording that will fit. Abbess Kasanoin weaves into her text stories passed down in the convent from earlier centuries, such as that about Princess Tsunenomiya in essay 17, which tells the story of convent performances of the noh play Dōjōji. And many of the references are to poems familiar to women well educated in traditional literature like the abbess, such as those from The Tales of Ise, the Man’yōshū, and other old anthologies. The poems themselves, as will be explained below, were translated by Janine Beichman, and the two translators synchronized their work in these sections.

While the usual histories tend to focus on the activities of governments and institutions, men, and militaries, intimate essays such as these by a female witness to passing eras make absorbing reading. When we can see through their window the life of Japan’s cloisters and the author’s view of twentieth-century history in prose that flows and reflects with its own verve and depth, we know what Japanese-to-English translation can achieve when in good hands.

The Poetry: Translating the Inner Abbess

Another outstanding feature of In Iris Fields is the poetry, but translation of poetry takes special expertise and a great deal of time and polishing. The essays include not only poems by the author herself but many others that are familiar to Japanese readers from the canon of their own literature. The editors also wished to add to both the Japanese and English versions of the book a large number of poems previously published by Abbess Kasanoin in two anthologies. Early on, Barbara Ruch approached Janine Beichman, professor at Daitō Bunka University, to undertake the task of translating the poetry. Taking time out from her research on Yosano Akiko and Ishigaki Rin (Beichman is known for her translation of poems by Yosano, as well as by Masaoka Shiki and Ōoka Makoto; please see SWET Newsletter No. 118, pp. 3–20), Beichman worked closely with the editors and Cary, as well as following her own sturdy poetic muse, in rendering the some 124 verses that add, many of them place in between the essays, a fresh and broadening dimension to the “gossipy, factual back story.” A few samples give the flavor:

I part from my friend

at lamplighting time and feeling

the finiteness of things

buy the evening paper

on Avenue Shijo

友と別るる灯ともし頃のはかなさを四条通に夕刊を買う

tomo to wakaruru hitomoshigoro no hakanasa wo shijōdōri ni yōkan wo kau

Is it only I

whose hand leaves off

copying the sutra?

A mountain warbler

soars over the Western Pagoda

写経す筆とどむるは吾のみか西塔わたる山時鳥

kyō utsusu fude todomuru wa ware nomika saitō wataru yamahototogisu

Abbess Kasanoin was a highly trained poet, as described by her nephew Kasanoin Hirotada in the prefatory parts of the book, and as is revealed by her own account of how she applied herself to mastering the poetic arts from the age of fifteen. Her verses record vivid images of her own life and sensibilities, and, as Beichman noted, “she’s describing her human side, her thoughts as an individual. You glimpse a mind filled with things that perhaps you’re not supposed to be thinking about when you’re meditating.” The fascination of these verses, Beichman found, was that the abbess had been able to balance those two sides of her life so beautifully. “In the essays what you get is more of the outer abbess, while in the poems what you get are things that maybe she didn’t have room to say to people in the everyday, but that she said to herself—and that’s what poetry is for anyway.” What makes the book really enjoyable, Beichman remarked, “is the full picture of a human being we get with both the prose and poetry.” There is sorrow:

What is happiness

someone asks, knowing

full well

my heart’s sorrow

仕合わせは何ぞと人は問ひかくる悲しき吾の心知りつつ

shiawase wa nani zo to hito wa toikakuru kanashiki ware no kokoro shiritsutsu

And there is joy:

Looking

at the morning rainbow

in the treetops

of the lonely garden

the soles of my feet grow cold

まさびしき庭の梢に朝虹のかかるを見つつ足裏冷えゆく

masabishiki niwa no kozue ni asaniji no kakaru wo mitsutsu ashiura hieyuku

Sometimes the interpretation of a poem is difficult to pin down. Beichman mentioned one instance in particular, for which she had to be careful not to misrepresent the original, no doubt intentionally ambiguous verse. The poem in question (from p. 83):

That half century

of mine during the war years

and then after

never recognized

now flowing far off into the distance

ねぎらはるる事なき吾の五十年戦中戦後も遠く流れて

negirawaruru koto naki ware no gojûnen senchū sengo mo tōku nagarete

“Was she bitter?” wondered Beichman, and when her informants turned out to be divided on the question, she decided to keep it as ambiguous as possible in English as well.

This is a bilingual volume, and while the Japanese prose and poetry is available a few pages away, the decision to put the Japanese (both kanji and romaji) into the English pages, the better to grasp the author’s voice in the original, is a fortuitous one. This convenience offers the opportunity to either simply enjoy Beichman’s sensitively rendered translations or to deepen one’s understanding of the Japanese by referring to them. A limited number of notes, added at the discretion of Cary, Beichman, as well as Ruch, illuminate some of the more difficult allusions and background.

Designing for Two Languages: A No-Barcode Book

In Iris Fields has two front covers. It is essentially two self-sufficient books in one, thanks to a carefully thought-out book design that feels natural to both the Japanese and the English reader. But, if a book has two fronts, where do you put the bar code, the (most-certainly unsightly) fixture that is now required on the cover of every book to be sold in bookstores? Thanks to the presence of Katsura Michiyo, executive director of the Medieval Japanese Studies Institute, at our May 23rd gathering, we heard the story of how this handsome bilingual volume came to be designed and the bar-code dilemma resolved.

Katsura, whose career has ranged from conference planning to Japan Society work and other internationally involved endeavors, clearly played a crucial coordinating role in keeping both this book and the exhibition catalog project on track to successful completion. Both projects involved the creative egos and energies of a large number of talented and very determined people, some more oriented to the Anglophile world, others more to the Japanese world. A person like her, familiar with the ways of doing things and the protocols of both, was essential.

Katsura recounted their search for the optimal bilingual layout and design and for a way of printing some copies that would be suitable as gifts. They were fortunate that the Kyoto-based publisher Tankōsha, which is well-connected with publishing of tea ceremony-related works, agreed to the Institute’s request to take on the project. Given the close connection of the convents to the imperial court, the Institute wanted in particular to have a book that would be suitable for presenting to the Imperial Household, and a volume stamped with an ugly barcode seemed hardly appropriate. Finally it was decided that half the print run would be made without bar codes (and thus would not be distributed via bookstores), while the other half would have the bar code, situated in the lower part of the English-side cover, to facilitate its sale mainly in Japan.

The layout of the two parts of the book echo each other but follow the behests of a vertically written language for the Japanese side and a horizontally written language for English. The print is rather small (all too common these days, it seems), but the typography is skillful and the fonts are well harmonized. Unobtrusive hair-lines divide the additional poetry from the prose text and set off the notes from the text. Numerous photographs add even further interest, and are sometimes slightly different for the Japanese and English versions, for an overall considerable total. The layout was done by Ueno Kaoru, a self-trained designer based at the Rosō Design Office in Kyoto. Her sensitive layout and typography make this book one that English wordsmiths and readers can really appreciate.

Sadly, Abbess Kasanoin sadly passed away before In Iris Fields could be completed, but the Institute was able to finalize the volume with an additional essay written by her after the Emperor and Empress visited Daishōji in 2004, a highlight in the abbess’s long life.

These days, when one is feeling overwhelmed by the wave of Web worship, it is indeed calming to pick up this lovely volume, which Tankōsha showed off at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2009. Its thoughtfully penned words, meticulous scholarship and translation, and discriminating design do what, short of going there in person, only a physical book can do—transport the reader into the world behind cloistered walls.

A Catalog of Scholarship and Art Commentary

The art catalog, Amamonzeki: A Hidden Heritage, meanwhile, came into being along a rather different trajectory, through research conducted under the Imperial Convent Research and Restoration Project of the Medieval Japanese Studies Institute aiming to bring to light the history and legacy preserved by the princess-nuns. This research has culminated in several other publications, including Chūgūgi Imperial Convent, the record of the World Monument Fund-supported project in 2007–2008 to restore the Royal Reception Suite at Chūgūji in Ikaruga, Nara prefecture. In 2003, Patricia Fister of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) had practically single-handedly spearheaded a small exhibit of works from some of the convents, held in Kyoto to much acclaim, for which she was the main author of a 90-page bilingual catalog (Art by Buddhist Nuns: Treasures from the Imperial Convents of Japan), published by the Institute. She and other scholars interested in the convents and their treasures, including Ruch, have published numerous articles and given talks and lectures over the years, quietly building up a corpus of research and reports on the temple’s histories, the women who founded and restored them, and their architecture, as well as the art works—calligraphy, textiles, furnishings and other objects of everyday life including games and dolls. Their efforts gained recognition and in 2005 set in motion preparations for the large-scale exhibition that was finally realized at the Tokyo University of the Arts in spring 2009. They made arrangements for treasures from 13 surviving imperial convents in Kyoto and Nara to be put on display, as well as for the exhibition catalog that would explain the exhibit’s extraordinary and diverse content.

Author-Translator Collaboration

The 384-page bilingual catalog pulls together the commentary of more than 10 specialists in diverse fields of art history including temple architecture and furnishings, textiles and apparel, paintings and calligraphy, dolls, cards and other games, eating and food-related implements, and writing and study equipment. The essays and commentary by these specialists were to be written originally in both Japanese and English, so translation would have to be done both ways for the final catalog. Fister asked Takechi Manabu and me, along with several colleagues, to take on the E-to-J and the J-to-E translation, copyediting, and proofreading in May 2008. Our own venture into the lore behind convent walls was also one into the inner sanctums of Japanese culture, here and there on topics we had not translated before in our three-decade careers. There were passages about the burial of the umbilical cord after the birth of an imperial princess; about rusu-e paintings that look like landscapes but incorporate motifs—immediately recognizable to the aficionado of noh drama—suggesting a subject who is absent from the picture; and about textile patterns, stitching, and weaves that can be translated beautifully, if only you know the right term. Even familiar topics took on new dimensions when part of the traditions of convent life.

The specialized nature of the manuscripts as illustrated by such topics and the limited time available to translate them at first filled us with dread, but we survived, thanks to Fister’s admirable managing editorial powers; she has overseen the completion of numerous monographs published at Nichibunken and is conversant and sympathetic with the hazards translators face. From the outset, she requested what we might term the “annotated manuscript” strategy, which calls on the authors to prep the manuscripts somewhat: those originally written in English would incorporate kanji for names, places, specialized terms, and so on; the Japanese manuscripts would include furigana or romanizations, along with explanations for the translator wherever possible. The annotated manuscript strategy—if it can actually be followed—would benefit even the smallest translation project.

When authors are well versed in both languages—even if they do not have the time or inclination to translate the material themselves—they can speed up the translation process considerably by providing correct readings for names and terms and other specialized knowledge. Some authors do this instinctively, but they are few and far between. Experienced translators who know their clients well may not hesitate to request these aids in advance. Most authors will respond to questions once the first draft of a translation is ready, but it’s even more efficient when the bulk of the questions can be answered from the outset. Excessive intervention by an author is undesirable, but for non-fiction texts that are specialized, constructive collaboration is much to be encouraged.

Thus the manuscripts that reached the translators were for translation manuscripts, containing material that was intended specifically for translator support. This proved invaluable for both the E-to-J and the J-to-E translations. The translated drafts were checked by the authors, and revisions were then made in response by the translators; style questions resolved, and matters of consistency with the rest of the catalog were also addressed.

One manuscript, however, languished, even with annotations. When specialized content reaches a certain saturation, the confidence of even a veteran translator can be shaken. We hesitated in awe at the fascinating but technically forbidding essay on textiles in the imperial convents written by noh drama and textiles expert Monica Bethe. Finally, by mobilizing her bilingual son, grappling with the Japanese herself, and having her work edited by fellow Japanese scholars, Bethe got her amazing article into Japanese. This was one of those instances in which the language barrier is much higher than usual.

Visualizing the content

Translators and editors of art-related material should insist on receiving visual reference materials with the manuscripts, since authors who are writing about art or other image-centered subject matter have images in their minds that the translator must be able to share. It is important to anticipate this need because, although some clients are familiar with sending links to photo album sites, offering URLs where the images are posted, or sending images on CD or memory stick, others are not. If clients are not yet comfortable with such conveniences, even if you can get color photo copies of the images, it will be better than nothing. Many museums and designers requesting translation are slow to grasp the translator’s pressing need to share images, but these can be crucial to an accurate rendering, so it is worth keeping your work hostage until the images arrive.

Fortunately, in our work on the catalog, the authors checking all the translations had seen the art works up very close and they knew exactly whether, for example, there were two puppies or one (an ambiguous point in the Japanese) on a temple hanging, whether a motif was on the “ends” or the “sides” of a furnishing (the words are the same in Japanese), and other subtle but important distinctions. But often a translator is on her own in having to make crucial decisions for a readership that will be focused on looking at the items described, and who might therefore end up with more information than the translator if the latter is in the dark about the visual part of the job.

How to make compactness readable

The exhibit catalog, it had been decided, would basically follow the Monumenta Nipponica (MN) Style Sheet, but some adaptations had to be made for what was to be a completely bilingual work. We looked at samples of page layouts, and it was decided that the Japanese and English texts would not be put either on facing pages or on the same page, as these design options force too much coordination between languages that act quite differently on the page. The Japanese version of each article would be followed by the English version, consecutively, throughout the book, and the designers had to make every effort not to waste space. In the end, by making skillful use of images and illustrations, they created a very attractive and readable bilingual work. Since the Japanese would appear immediately before the English, the MN method of including kanji in the English text was modified and used only when the kanji were deemed necessary to the discussion.

Handling the notes and bibliographies that accompanied each article in the catalog caused of some amount of trial and error. Footnotes would have been nice, but they chop up the page layout too much, and coordination on the page is always tricky. Endnotes proved the better solution.

In order to pack a tremendous amount of text onto a limited number of pages, the initial design featured A4-size pages with text, notes, and bibliographies all stretching over 15-centimeter-long lines in 8- and 6-point type. The tiny point was excruciating to read! Without delay, we persuaded the designer to switch to two columns, a layout in which smaller type is easier to read, and also accommodates more text. The type in the published work is still too small—the general rule being that the smallest acceptable main text size for printing is 10 points—but we had to accept it.

The editorial and design offices earned the admiration of all involved with the catalog for their dedication and professionalism. Fister and I took responsibility for the English editing, but the vigilant copyediting eye on the Japanese text of Kimura Shinobu of Office Fukumoto in Kyoto, who has gained much experience with art exhibition catalogs, worked something of a miracle in the final taming of the more than 100 Japanese and English manuscripts from ten authors and eight translators. The page layout and typography were done by Sakamoto Yoshiko of Ohmukai Design Office in Kyoto. Particularly impressive was these individuals’ willingness to listen to the advice of those of us representing the English readership and to adapt their design in response to our appeals.

Keeping tabs on complex content

To keep tabs on the more than 50 texts that made up the catalog—100 in both languages—we worked out an identification system for the manuscript files, assigning section and manuscript numbers in order throughout the book. The file names contained these numbers along with “E” or “J” to identify the language of the file’s text, the initials of the last person to work on the draft, and sometimes those of the previous person as well. This resulted in file names like “02-3-J-Zen Painting2-10-09AM-LER-PF” (third article in the second section, Japanese translation, copyedited, and edited) and “03-3-E-Tanaka1-31-09TM-CI-PF” (third article in the second section, English translation, author checked, translation revised, edited), telling us where a manuscript lay in the book, where it stood in the editorial process, and who had seen it. Footers in the files with similar information—especially helpful when manuscripts are being printed out at certain stages—also helped keep track. This system works well for designers and printers, too, especially when the operators are not native speakers of English and are handling files as chunks of text rather than content they actually read.

Thanks to the extraordinary cooperation of authors, translators, designers, proofreaders, and the staff of the Medieval Japanese Studies Institute, all carefully guided along by Patricia Fister, who has the patience of a saint, the catalog stuffed with information was completed on time for the exhibition’s opening. Midway through the final stages of translation and editing of the catalog, the completed book In Iris Fields became available, and we devoured this personal story of the abbess of one of the imperial convents, which brought vividly to life the very art objects that we had been translating about for the catalog.

At the May 23rd meeting, Cary, Beichman, Katsura, Fister, and I—all of us acquainted with each other even before these two projects—shared the irony that the work on the book and the catalog had taken place quite separately. We had been aware that we were working on related projects, but had been so absorbed in the tasks at hand that we were unable to connect the dots and get in touch until the very end. Even in our small professional world, when work is all-absorbing, we can charge ahead without any idea that we are not far away from each other. The finished products, however, form a nicely complementary pair, two works of very different kinds, but both produced as endeavors to bring history and traditions alive.

(Originally published in the SWET Newsletter, No. 123, October 2009; republished with permission 2020; © 2009 Lynne E. Riggs.)

[1] The amamonzeki are temples founded and headed throughout history to the Meiji era by abbesses who were daughters of emperors and women of the shogunal and high-ranking warrior classes as well as—in the modern era—by women of aristocratic families. The temples were unusual even in Japan for the highly refined and relatively worldly lifestyle of the highborn women within them and the traditional culture that formed the structure of their daily lives and which they have preserved for centuries to the present.