September 20, 2012

Journeying with J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965

by Avery Fischer Udagawa

Shogo Oketani, author of J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 (Stone Bridge Press, 2011), and his wife, Leza Lowitz, spoke to members of SWET and SCBWI Tokyo on December 6, 2011. Avery Fischer Udagawa, the translator of J-Boys, joined via Skype in the exchange, which was moderated by Holly Thompson at the Wesley Center in Minami Aoyama, Tokyo. The conversation traced the development of J-Boys from linked stories in Japanese for teens and up to a novel in English for middle-grade (upper-elementary) readers. Udagawa reflects further on the education the project afforded her in middle-grade historical fiction.

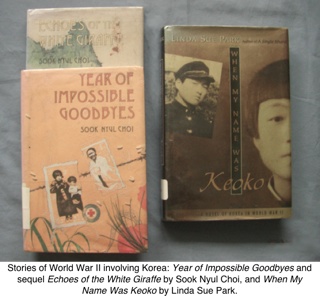

1941: In Hawaii, a Japanese-American boy kills his father’s racing pigeons to avoid charges of subversion after Pearl Harbor. 1942: In Long Beach, California, a girl watches her mother smash family china rather than sell it before being forced to leave home. In Berkeley, a girl worries about her father, who is being held in Montana, and about leaving her dog when the family “evacuates.” Meanwhile, in Korea, a girl teaches a neighbor to count in Japanese, to avoid punishment at neighborhood roll calls. In Pyongyang, a girl struggles to sing Kimigayo at a school assembly, as her teacher jabs her with a ruler. 1945: In Hiroshima, a girl watches the horrors of the atomic bomb. Ten years afterward, a girl much like her folds hundreds of paper cranes to ward off death from leukemia.

The novel J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 tells the story of a nine-year-old boy who lives in working-class Tokyo in the mid-1960s. As the translator of this book by Shogo Oketani, I fully expected to learn about public bathhouses, kamishibai, the Tokyo Olympics, and cultural imports like the Beatles and Leave It to Beaver. I did not anticipate exploring other historical periods from the perspective of Asian and Asian-diaspora children—a task that began some three years after translating, when the editorial team tailored J-Boys for the North American middle-grade (MG) book market. The process of focusing J-Boys for English-language readers ages eight to twelve prompted a look at MG editorial requirements, existing historical MG titles related to Asia—from which the images opening this article were taken—and the titles for youth that are (and are not) coming out of Japan in English translation. In this article I will recap the journey of J-Boys and share a few discoveries made along the way.

From Inspiration to Translation: The Journey of J-Boys

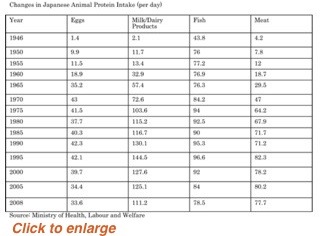

As Shogo Oketani described in his presentation to SWET and the Tokyo chapter of SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators) on December 6, the book J-Boys began with a single story about tofu that grew into fifteen tales about Kazuo Nakamoto, a boy whose life  illustrates the differences between Japan in the 1960s and Japan today. Oketani showed a chart of increases in Japanese people’s animal protein intake from the mid-twentieth century through the early twenty-first century, and discussed other tangible aspects of life that he worked to capture through his stories about Kazuo. Oketani continues to live on the property in Shinagawa ward where he grew up in the 1960s, and which he chose as the setting of J-Boys, so he has personal experience of the changes experienced there. He shared several archival photos of Shōwa-era working-class Tokyo to highlight contrasts between life then and life today.

illustrates the differences between Japan in the 1960s and Japan today. Oketani showed a chart of increases in Japanese people’s animal protein intake from the mid-twentieth century through the early twenty-first century, and discussed other tangible aspects of life that he worked to capture through his stories about Kazuo. Oketani continues to live on the property in Shinagawa ward where he grew up in the 1960s, and which he chose as the setting of J-Boys, so he has personal experience of the changes experienced there. He shared several archival photos of Shōwa-era working-class Tokyo to highlight contrasts between life then and life today.

Oketani’s wife, Leza Lowitz, described how she had encouraged him to write the initial stories, which he then developed into the collection that she hired me to translate in 2008. She pitched my translation to Peter Goodman at Stone Bridge Press, who accepted the manuscript in 2010 and published the book in 2011. In the pre-publication phase, Lowitz sought key input from Japan-based authors Holly Thompson and Suzanne Kamata, who urged the team to shape J-Boys—potentially a teen or adult work—for middle grade readers, due to the main character’s age and the MG-appropriate voice and point of view threaded through much of the book. This feedback led Lowitz to request a significant yet sensitive reshaping of the text by author and editor Susan Korman. Oketani, Lowitz, Goodman, and I then conducted editorial passes to follow up on Korman’s changes.

Further details of the group effort to develop J-Boys from story to collection to novel in translation can be found in the Spring/Summer 2011 issue of Carp Tales, the newsletter of the Tokyo chapter of SCBWI, beginning on page 4.

Shortening, Lightening Up, and Speeding Up

A close look at the editorial changes to J-Boys reveals that a lot, and little, happened. The editors worked to reduce the length of the book from more than 64,500 words to about 40,000, and to make the narrative speedier, lighter, and consistently told from a child’s point of view. Korman advised that the MG market required shorter sentences, simpler words, reduced backstory and details, and avoidance of overly adult observations. Some tweaks to titles were suggested to make them more kid-friendly; for example, a story originally called “Kazuo’s Dirty Mind (Keiko Sasaki’s Story),” about a girl in Kazuo’s class, became simply “Keiko Sasaki.” Also recommended was a change in the main character’s age: Kazuo went from age eight to age nine so as to attract more grade-schoolers, who tend to “read up” about characters older than themselves.

The cuts and changes to the text did not sacrifice many significant story developments, but they imparted a slightly different overall feel. To “show rather than tell” about the differences, following this article are several endings of stories given first in my original translation, and then in the edited version. Lowitz read these excerpts aloud with Thompson on December 6 and graciously provided them for use here.

J-Boys among MG Historical Books Related to Asia

|

In the process of preparing J-Boys for market, it became necessary to read other MG historical books related to Asia, both to identify a “niche” and to find authors from whom to request cover endorsements.

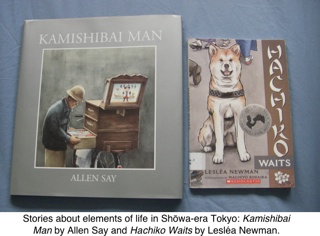

In this reading stage, I was delighted to find a wealth of material portraying certain moments in history from the perspectives of Asian children, fictional and real. For example, I found a number of stories set during and after World War II that complement the famous child’s-eye view of Anne Frank. I was pleased also to encounter moving stories set in my native United States that explored Japanese-American children’s experiences. Finally, I learned of short, highly focused books about aspects of life in early- to mid-twentieth-century Tokyo such as the Shibuya statue Hachiko and the storytelling form of kamishibai, both of which appear in J-Boys.

I soon discovered, however, that J-Boys stands alone as a realistic historical MG book about Japan centered in the non-conflict period of the 1960s. It is also unique in that it is lengthy enough to encompass multiple social and cultural themes from that time and show how they intersect. In addition, I learned from librarians and teachers that J-Boys could fill a gap in classrooms as a work of non-U.S.-based historical fiction; as a book involving complex social issues (such as anti-Korean discrimination in Japan) that has vocabulary simple enough to accommodate ESL readers; and as an MG book about a boy, since many MG books feature female protagonists. In addition, J-Boys contributes through being a translated work written by a Japanese man who grew up in its setting, versus a work originally written in English by a non-Japanese author.

As a translator and co-leader of the SCBWI Tokyo Translation Group, a network of children’s literature translators, I had been aware that acclaimed translations of children’s books from Japanese include few historical titles. The Japan-born winners of the prestigious Batchelder Award, for example, include just one historical title, Hiroshima No Pika, by Toshi Maruki, which is a  picture book. I doubt most Japan-watchers would say the Batchelder winners from Japan represent a balanced sampling of Japanese children’s literature or a comprehensive look at the Japanese experience; while excellent, they also highlight what remains to be filled in by authors, translators, and publishers who are motivated to shape Japan-centered texts for the U.S. youth market.

picture book. I doubt most Japan-watchers would say the Batchelder winners from Japan represent a balanced sampling of Japanese children’s literature or a comprehensive look at the Japanese experience; while excellent, they also highlight what remains to be filled in by authors, translators, and publishers who are motivated to shape Japan-centered texts for the U.S. youth market.

For the above reasons I found it heartening, from the standpoints both of marketing and of seeking to bridge cultures, to see that J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 would fill a gap.

Middle Grade . . . and Up?

One question that remains in my mind after the editing and reading processes is whether J-Boys will now reach middle grades and up in English, as indicated on its cover. As a parent I find that reading children’s books is often enriching for me as an adult, but the child-to-adult market that seems well established in Japan is not always present in North America. Did preparing J-Boys as MG help it reach English-reading teens and adults as well as children? Do the changes that make it appropriate for eight- to twelve-year-olds make it a more accessible read for over-twelves, as well? Time will tell. This period of examining market response is the current stage on the journey of J-Boys.

J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 . . . Before and After

Below are excerpts from endings of several stories in J-Boys, first in the original translation by Avery Fischer Udagawa and then as edited for publication by Stone Bridge Press as J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965.

From “The Tofu Maker”

Kazuo was remembering what Mr. Yoshino had told him, that growing up strong so his parents wouldn’t worry was the most important thing he could do for them. He pictured the tofu maker’s red, swollen hand drawing out the tofu.

His hand was like that because even in the cold, it had brought the tofu up very carefully so as never ever to break it.

“From now on, I’m going to chew my tofu when I eat it. And I’m going to do my homework without Okaasan telling me,” Kazuo thought to himself as he brought his food to his mouth.

But he couldn’t help regretting that he could never again eat tofu drawn out of the water for him by Mr. Yoshino’s red, puffy hand. And he felt bad that he had never eaten that tofu while realizing just how good it really was.

Edited:

Kazuo suddenly remembered what Mr. Yoshino had said: that growing up healthy was the most important thing he could do. He pictured the tofu maker’s red, swollen hand drawing out the tofu.

From now on, I’m going to remember to chew my tofu when I eat it, thought Kazuo. And I’m going to try to do my homework without my mom telling me to do it.

He felt bad that he’d never realized just how good Mr. Yoshino’s tofu really was until now.

From “Yasuo’s Big Mouth”

“Did you know all the time why that lady was holding the doll?”

“Of course I did,” Yasuo answered, tilting his head slightly toward Kazuo.

“Then why did you ask its name?” Father asked, looking over at his younger son.

“Because the two of them looked so lonely! I figured they wanted to talk to somebody, so I decided to say something.”

“Really?” The three others nodded as though persuaded, and once again turned their eyes to the city lights that were passing by.

Maybe Yasuo wasn’t as much of a child as he’d thought, Kazuo reflected. He wasn’t just saying the first thing that came to mind, like when he was little. He was thinking about how to address other people. Just as Kazuo was beginning to think of himself as no longer a child, Yasuo must be growing up in his own way, Kazuo thought.

And he hoped that for the four people in his family, and that white-haired couple, the coming year would be a good one.

Edited:

“Then why did you ask its name?” Father wanted to know.

Yasuo shrugged. “Because the lady looked so lonely. And you know me,” he added with a sly grin. “I like to talk!”

“That’s for sure!” exclaimed Kazuo, and everyone laughed. Then once again Kazuo turned to the bright city lights that were streaming by. Maybe Yasuo wasn’t as much of a child as he’d thought, Kazuo reflected.

Kazuo silently wished his family, and that white-haired couple, a happy New Year. Another year had come upon them, and things were already changing, right before his eyes.

From “What Wimpy Ate”

While feeling somehow disappointed, Kazuo looked around at the crowd in the shopping district. Within that crowd, he saw a girl about the same age as Yasuo holding hands and walking alongside a man who looked to be her father. The girl seemed pleased to be walking with him, and was chattering on and on with him while wearing a big smile.

Kazuo happened to think that even Mother had been a little girl like that once, and that she had probably held hands with Grandfather happily and walked along smiling at him, just as the child in front of him was doing. That would have been a natural thing for them to do as parent and child.

And even though there were ill feelings between them now, surely they would make up someday, he thought. Because, after all, he was her father and she was his daughter.

But just as the hanbaagaa that Wimpy ate remained a mystery to him, he had no idea when such a thing might come to pass.

Edited:

Kazuo suddenly spotted a girl in the crowd who was about the same age as Yasuo. She was walking alongside a man who was probably her father, holding his hand. She was chattering on and on while wearing a big smile. Her father smiled back.

Mother was a little girl like that once, Kazuo realized suddenly. And she had probably held hands with Grandfather and walked along smiling at him, too. So maybe someday they would make up because, after all, he was her father and she was his daughter.

But Kazuo did not know which thing would happen first. Would he eat a real hamburger, the kind that Wimpy liked? Or would Okaasan and Ojiichan finally begin talking to each other again?

From “Kazuo’s Journey” (Originally “Spring: Enfance finie”)

With the same look as that young traveler in the clouds overhead, Kazuo gazed steadily up at the sky.

Would he, too, be able to catch a fleeting glimpse of foreign countries far away? Feeling a mixture of expectation and anxiety, he stared into the blue of the sky as the young traveler drifted away astride the cloud camel. The blue of the sky was pure as far he could see, and seemed to engulf him. There was nothing but the blue of that sky.

Supposing that somewhere beyond the sky he could see the scenery of a foreign country far away, it would probably be very different from the images of foreign countries that he had seen on television.

Vivid green grass carpeting the garden, a living room with a fireplace and roomy sofa, a private room and bed for each person, a huge refrigerator stuffed with more food than you could eat. Jugs of milk so big that you would have to wrap both arms around them to pick them up, gigantic cars, freeways that went on forever, the hanbaagaa that Wimpy ate . . .

Those images were like a mirage that always floats in the air, moving further away even as you follow and gain ground on it, Kazuo thought. He knew he was beginning to understand that foreign countries were more than a world in which everything was larger than life and people’s homes overflowed with stuff. Up until the previous year, he had always thought of countries overseas as places where tall people with white skin lived—lands of skyscrapers so tall they stuck through the sky, quiet and beautiful townscapes, abundant food and spacious houses and cars.

But he was beginning to see that foreign countries were not places filled with only beautiful scenery. He thought of Vietnam, where there were air raids almost every day and people were running for their lives; Africa, where children his own age were starving and dying one after another, their stomachs grossly distended; and North Korea, where Minoru had “returned” with his family. Those were foreign countries, too.

And in those places, it was not the case that everything was always beautiful and wonderful. Suffering and sorrow had existed, and probably continued to exist, as daily realities, just like they did here—no, far more than they did here.

Kazuo stood up and brushed some slightly damp earth, which smelled of new grass, from the seat of his pants. The cloud camel and traveler that had passed over his head had at some point lost their shape, and now looked like a fish with a prominent dorsal fin. But that young traveler was definitely still somewhere in the sky, continuing his journey toward the foreign land he could not yet see—even if the land he dreamed of, full of untold beauty and repose and prosperity, did not exist. And that is as it should be, Kazuo thought, gazing with the young traveler’s look upon the city where he lived, which certainly could not be called beautiful.

Low wooden houses, packed close together as if holding each other up, stretched on and on, looking like beasts with dull, black hides quietly huddled together. Here and there in their skin were a number of openings, and the wind that blew inside them passed straight through the stiff, aging joints in the animals’ legs, making a whistling sound like a small flute.

But that would only last as long as winter did. Now that the cold, long winter was coming to an end and spring was arriving with its warm rays of sunlight, the beasts would probably breathe a sigh of relief and slowly stir, then depart for lands to the south that offered abundant grass and water.

“Someday I, too, will leave this town, and this country.”

Kazuo looked at the part of town where roof overlapped roof in the most densely built area of all, full of dark black shadows.

“Maybe the world outside of here isn’t as full of beautiful places as I dream it is. Still, I imagine I will go away from here, and maybe in a foreign country I will meet up with many other people who left the places where they were born, like me, and have the same look as that cloud-traveler in their eyes.”

Thinking about it made Kazuo’s heart leap a little in his chest.

Maybe at that time, his father would no longer get drunk and tell him to enter a national university, earn a degree at graduate school, and work at a top corporation. And maybe his mother would no longer say “during the war,” and would have mended her ties with Kazuo’s grandfather. And just maybe, Yasuo would finally be raising the dog he had waited and waited for. And as for Kazuo himself . . .

Today the flag of memory comes down, and like a river, I take my leave.

On the floor are my footprints, in my footprints a faint dust . . . sadness.

I will . . . I must . . . leave on a journey far away.*

Kazuo, still but ten, did not yet know the sorrow of leaving home.

*Lines of poetry by Tatsuji Miyoshi

Edited:

Kazuo gazed at the sky and pictured himself as a questing traveler.

Though he imagined that somewhere beyond the sky he could see the landscape of a foreign country, he knew that it was probably very different from the far-off countries shown on TV. In those images, each home had vivid green grass in the yard, a living room with a fireplace and roomy sofa, a private room and a bed for each person, and a huge refrigerator stuffed with more food than you could ever eat. There were jugs of milk so big that you would have to wrap both arms around them to pick them up, skyscrapers so tall that they stuck through the sky, gigantic cars, freeways that went on forever, and the hanbaagaa that Wimpy ate . . .

But Kazuo was beginning to realize that foreign countries had disturbing as well as beautiful scenery. He thought of Vietnam, where there were air raids almost every day and people were running for their lives; of Africa, where children his own age were starving and dying one after another, their stomachs grossly swollen; and of North Korea, where Minoru had gone with his family, and had mysteriously fallen out of touch. Those were foreign countries, too.

And in those places, it was not true that everything was always pleasant and wonderful. Suffering and sorrow had existed, and probably continued to exist, as daily realities, just like they did in Japan—or even far more than they did here.

Kazuo stood and brushed the seat of his pants, sweeping away moist earth that smelled of new grass. The cloud camel and traveler had passed over his head and at some point had lost their shape. He stared in their direction.

“Someday, I will leave this city and this country. I’ll meet many other people who left the places where they were born, like me.”

Thinking about it made Kazuo’s heart leap a little in his chest.

Maybe by that time, his father would no longer get drunk and tell him to enter a national university, earn a degree at graduate school, and work at a top company. And maybe his mother would no longer say “during the war,” and would have mended her ties with Kazuo’s grandfather. And just maybe, Yasuo would finally be raising the dog he had waited and waited for. And as for Kazuo himself . . .

For now, he still lived in a world called Tokyo.

He looked out at his city. The small houses huddled closely together, like a group of animals still sleeping on a meadow in early spring. Soon, they would feel the warmth of the sun, and they would start their journey toward a new, green field.

Kazuo felt he could run as fast as a four-legged animal, perhaps a gazelle. He took a breath of fresh spring air and sprinted off toward the horizon.

Originally published in SWET Newsletter No. 130 (May 2012).

©2012 Avery Fischer Udagawa