July 8, 2009

Kurodahan: Selling to a Niche

by Ginny Tapley

Based in Fukuoka, Kyushu, far from the usual centers of publishing, Edward Lipsett, Stephen Carter and Chris Ryal have established Kurodahan Press, a new type of publisher now entering its fifth year. Having started with Mayumura Taku’s Administrator in 2003, Kurodahan specializes in translated Japanese literature, particularly genre fiction such as science fiction, horror, fantasy, and mystery. Ultimately, however, they aim to build up a solid line of East Asian fiction and non-fiction for both specialist and non-specialist readers. Ginny Tapley talked to founder and SWET member Edward Lipsett.

Kurodahan is an unusual type of publisher in many respects, not least the way you appear to be bypassing the traditional distribution networks in favor of using new print-on-demand technology. Can you explain how this works?

POD is a printing technology, not a publishing technology. It simply means that instead of using an offset press to print many books, a much simpler machine is used to print the number of books required to fill an order. The actual distribution is identical: our books are also offered through Ingram in North America, Bertrams in the United Kingdom and Amazon worldwide (including Japan). In North America and Europe they can be ordered from any bookstore through the regular book distribution channels.

In Japan on-demand printing is evolving into a vehicle for small-scale selfpublishing such as local histories and “haiku circle” type publications—which, in Japan, is a much more important publishing niche than in North America—and while the systems are technically very good, they are not set up to handle the needs of publishers like ourselves. As a result, we ship books from the United States to serve customers here in Japan.

Traditional publishers are hampered by expensive print runs of several thousand at a time. Do you only print according to the orders you receive?

Yes. Plus a healthy stock on hand to send out for promotions, to authors and translators, and whatnot.

What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of print-on-demand? Do you have problems getting your books into bookshops, or getting them reviewed?

The biggest single advantage is that we don’t have to pay to print several thousand copies up front or have a place to store them or ship thousands of copies knowing that we will some day get many of them back in poor condition, etc. The distributors and Amazon handle all the money matters for us, which is also nice. We can update the cover or the text at any time for a nominal fee, and all copies sold after that point automatically use the corrected data.

The biggest single advantage is that we don’t have to pay to print several thousand copies up front or have a place to store them or ship thousands of copies knowing that we will some day get many of them back in poor condition, etc. The distributors and Amazon handle all the money matters for us, which is also nice. We can update the cover or the text at any time for a nominal fee, and all copies sold after that point automatically use the corrected data.

There are some disadvantages, though: POD costs a heck of a lot more per book, which means our books are priced a bit higher than we would like. Many stores, reviewers, and customers avoid on-demand books regardless of content. And the very fact that they are not printed in volume makes it impossible to distribute them to every bookstore throughout New York or Tokyo.

Given the astonishing number of books published every year, it is very difficult to get your book into a store at all, and when you have the disadvantages of a slightly higher price and a printing technology that the trade still regards with suspicion, it is close to impossible. That said, we are stocked in a number of specialty shops (horror and science fiction), including both online and brickand-mortar stores.

Many of your titles are genre fiction such as horror, science fiction, fantasy, or mystery, and also collections of short stories. What prompted you to specialize in this way? Who is responsible for selecting the stories?

Japan has a lot of literature worthy of translating, but unless it aims at a fairly special niche, it will just be lost in the flood. We are trying to select books that have significance in translation, and that also have a nice niche we can sell to. Horror and SF are luxury books, basically, which means pricing is quite a bit more relaxed than for, say, a toaster.

Japan has a lot of literature worthy of translating, but unless it aims at a fairly special niche, it will just be lost in the flood. We are trying to select books that have significance in translation, and that also have a nice niche we can sell to. Horror and SF are luxury books, basically, which means pricing is quite a bit more relaxed than for, say, a toaster.

We accept ideas from many people about books worth translating, and also receive a number of unsolicited manuscripts. Two of our most promising books, now in progress, came to us out of the blue. Other books we decided to go with ourselves. Once we like a book, though, we still have to locate the rights holder and settle the details. Usually this is not a problem, but we have lost several very exciting books because we were unable to find a workable arrangementwith the rights holder.

Can you expand a little on the niche market issue? How does this differ from mainstream bookselling, both in terms of what readers are looking for and how publishers reach their readers?

Science fiction, horror, crime, and the like are specialty markets, and only appeal to a subgroup of all readers. They are still outcasts in bookstores, to some extent, and generally have their own little sections back behind the bestsellers. Unless it’s Harry Potter, of course…People who wander through a bookstore or airport kiosk looking for something to read on the way generally grab a thick, heavily-advertised, eminently forgettable Clancy or Forsyth, for example. Extensive advertising is only useful if you can expect to sell the tens of thousands of copies needed to pay for it, and that is exceedingly unlikely with SF.

You attended the 2007 World Science Fiction Convention in Yokohama. Can you tell us a little about that, from a publishing perspective?

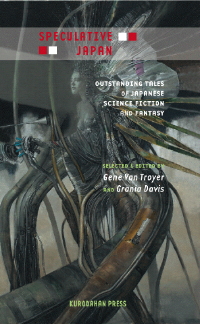

The entire affair was strictly a public relations gig. We released the Speculative Japan SF anthology there at a special introductory price, but basically our goal was to meet a lot of people in the industry and do what we could to make people aware of the fact that we exist. Sure, we lost money on it, but who knows what word-of-mouth advertising might bring us in the future?

The entire affair was strictly a public relations gig. We released the Speculative Japan SF anthology there at a special introductory price, but basically our goal was to meet a lot of people in the industry and do what we could to make people aware of the fact that we exist. Sure, we lost money on it, but who knows what word-of-mouth advertising might bring us in the future?

I also got to see lots of old and new friends like Shibano Takumi, Komatsu Sakyō, Hori Akira, Asakura Hisashi, Charles Stross, Ellen Datlow, Inoue Masahiko, and Chris Bolton, just to drop a few names. Not to mention all the Japanese publishers in the field, like Hayakawa and Tokyo Sōgensha. The foreign participation was unfortunately pretty low, but knowing people is a crucial part of succeeding in the publishing business. Pretty much like the translation business, actually, now that I think about it.

Do you attend, or have plans to attend, other major book fairs like Frankfurt, London, or the ABA?

No plans. As I mentioned above, we can’t provide full distribution to the market. We do send copies to agents who may be able to sell rights to have them translated into other languages, but outside of sending out lots of review copies and letters, that’s about all right now. Once we achieve a bit of a name in the fields we handle it may be worth the investment in the future, but it will just have to wait.

How do you select translators, and what qualities are you looking for?

Our translation test is online, with instructions. It is impossible to judge how good a candidate may be from a translation test, but it is usually possible to identify people who are outstandingly bad. Once we decide a person may be qualified, the best thing to do is let them try their hand at a short story, because it is short enough to assign to someone else later if it turns out to be done badly. Yes, this has happened, and when it does happen any translation we have received is discarded, and is not provided to whomever tries translating that work next.

We normally request partial deliveries of works in progress, both to make sure that translators stay on schedule (which is usually ample), and to provide feedback on potential problems before they become fatal. This approach has worked very well for us. We have also provided feedback on particular problems people have, working with them to improve their output (at least, that’s what we think…they may well have a different opinion). This has also worked very well, with several people showing a marked improvement from literal translation to literary translation.

Qualities? Impossible to define, but basically to be capable of presenting the original Japanese in the tone of the original, in smooth and enjoyable English, and with enough of the original atmosphere left to make it clear the book isn’t set in Peoria, while at the same time eliminating the need for footnotes or other mood-breakers.

You say on your website that you don’t mind whether translators use American or British English. Do you have a policy of using, say, just American English and edit accordingly, or do you publish in whatever English the translator used? What about in anthologies?

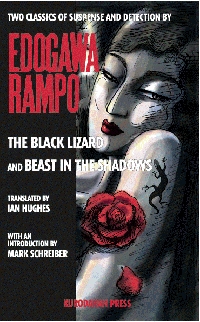

Our anthologies mix stories done in both. I grew up with American-style English, and Ryal with mainly British-style, but we accept the fact that both are perfectly correct. Normally we leave it up to the translator, but for our first Edogawa Rampo book, for example, we specifically wanted to move it closer to British English because it just sounded so much better for the setting.

How do you oversee the translation process, and who edits the translations and to what extent?

We receive translations in pieces, normally quarters, and try to provide feedback before the translator can get far into the next piece. For a translator we haven’t worked with before we do a total translation check, marking corrections and suggestions using Word revision tracking, and also providing general suggestions as to style, changing passive to active, combining multiple one-liners into paragraphs, how to handle special Japanese words or things, etc. The translator has responsibility for doing an accurate correction, and may (and sometimes does) overrule our comments. So far we haven’t run into a situation where one party couldn’t accept the other’s suggestion or find middle ground. A translation in progress might undergo half a dozen versions before it is ready for final copy editing, and there are usually two or three edits, again all made with revision tracking on and input from the translator. Sometimes the author also has input, but usually they are content to leave it in our hands.

How do you ask your translators to deal with tricky translation issues, such as untranslatable words or cultural concepts? Do you favor using footnotes and introductory essays, and such like, or do you prefer the text to stand on its own?

For general fiction (as opposed to fiction also meant for specialist use, like The Edogawa Rampo Reader) the goal is to preserve the Japanese flavor while removing stumbling blocks. Introductory essays are excellent, especially when the work requires placement within the Japanese milieu, but footnotes are almost always out. We have no objection to working in a description of a Japanese word, and then using the Japanese word thereafter, for example. We also have no objection to dropping or changing points that have no particular bearing on the work, where it would require massive explanation to get the point across; word play based on kanji homonyms, for example, just doesn’t work in translation very well. It’s not impossible to do, but if it’s only an offhand comment it might be better to avoid trying.

For nonfiction and specialist books, such as our forthcoming book on Queen Himiko and the ancient Chinese histories of Japan, or the Matsumoto Seichō Reader, the situation is different. Here footnotes are essential, and provide important background information, among other things. Of course, they still have to be done in smooth, readable English.

Are there any particular challenges that face translators when tackling science fiction? What about other genre fiction in general?

Science fiction in Japan is much the same as science fiction everywhere: it covers the entire spectrum. Japanese fiction, however, including SF, can be quite a bit different. As Grania Davis, one of the editors of our Speculative Japan anthology of Japanese SF writes in her afterword, “…the very best Japanese SF&F tends to be mood-driven, instead of action-driven.” It is not uncommon for a Japanese story to consist of only a setting, or a single scene, with no conflict, no climax, and no conclusion, or for a novel to sketch out a conflict but leave you hanging like Stockton’s The Lady or the Tiger?

And if a story is primarily mood, think how complex it must be to have to translate the mood of a New Year’s nengajō or Obon incense or something as common as a whole family using the same bathwater, into English. And when all these cultural clues are parts of a developing story or novel, the translator has to make tough decisions about which ones to delete, which ones to explain in passing, and which ones to localize.

Can you give us any idea of the sales figures you have been getting on your books?

Small. We are a small press, in every sense of the word, and sales of 1,000 copies is pretty much the high end so far. On the other hand, we have seen massive growth from last year to this year, and we expect this to continue as our advertising begins to pay off with name recognition, and readers continue to purchase new books from us. Also, a number of our books are already being used by teachers as course texts.

Have things gone according to plan? Have you had any big surprises or disappointments?

Pretty much as planned, I think. We didn’t expect to make any money at this for at least a decade, and that part is right on target. Big surprises? Yes, a few authors who kindly agreed to let us publish works although we were sure they would refuse, and likewise there were a few books that we really, really wanted to do but couldn’t. There are a lot of books to choose from, though, and I think we have enough to keep us busy for a while yet.

How do you see Kurodahan Press developing in the future?

In the short term, business as usual—although we are considering establishing the company as an independent corporation and would welcome hearing from people interested in participating, with or without capital. Our long-term plan calls for a transition from on-demand printing to full offset printing, and a major boost in advances and royalties paid to translators and rights holders. Both of these will have to wait until our cash flow is a bit healthier, but already we are making progress.

We used offset printing for our new anthology Speculative Japan: Outstanding Tales of Japanese Science Fiction & Fantasy, which was released at “Nippon 2007,” the World Science Fiction Convention in Yokohama. This is very exciting for us for a number of reasons: it is our first English-language book with a conventional print run, it is a very important anthology for Japanese in translation, and it marks a very important stage in our development.

Starting from 2009 we will be working on a new series of anthologies featuring representative works in the mystery, horror, and kaiki genres. This will be a major step for us: we’re looking at a series of half a dozen books covering all the major authors from Taishō to Heisei. We are working with Japanese anthologists to create books that truly represent this part of Japanese literature. It is fair to say that no one has tried anything like this before, and we hope to draw on as many translators as we can.

In addition to this, we’re already thinking about our next science fiction anthology, and books in the editing stage include a new and very important collection of works by Rampo, several novels, a late-Meiji travelogue and a look into records of ancient Japan (including the storied Queen Himiko) in Chinese histories, which will be a major work in English in its field of study.

Originally published in the SWET Newsletter, No. 119 (April 2008).