May 28, 2008

On Wakame and Bicultural Fiction for Children

by Avery Udagawa

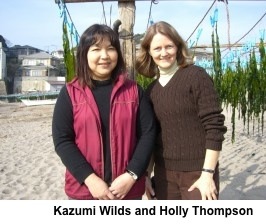

SWET core member and regional advisor of the Japan chapter of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI), Holly Thompson has lived in the Kamakura-Yokohama area since 1998 and teaches poetry and fiction writing at Yokohama City University. She is the author of the novel Ash (Stone Bridge Press, 2001) and recently made her debut as a picture book author with The Wakame Gatherers (Shen’s Books, 2007), the story of a bicultural girl who gathers wakame with her Japanese and American grandmothers. In this interview, Thompson shares some of her experiences writing and marketing The Wakame Gatherers, a rare example of bicultural fiction for children set in Japan.

Q. When did the idea for The Wakame Gatherers crystallize in your mind, and how did you proceed to shape and market this book?

Q. When did the idea for The Wakame Gatherers crystallize in your mind, and how did you proceed to shape and market this book?

A. I have always been fascinated with the various types of seaweed harvested in Japan—hijiki, tengusa, wakame, konbu, nori. Over the years I’ve observed seaweed harvests in Kamakura and along the west Izu coast. Having grown up in New England near the shore, where I loved tide-pooling on rocky shores among seaweed, I was puzzled as to why Japanese have eaten seaweed for centuries while in New England few varieties are considered edible. As I began to research wakame and the cultivation practices in Kamakura, I knew this cultural difference was something I wanted to explore in a story. My bilingual daughter often accompanied me on my seaweed forays, and as I began to think about her childhood in Kamakura, as well as her bicultural friends from different parts of Kanagawa and their experiences with their non-Japanese relatives, I came to realize that I wanted the story to feature a child who navigates two cultures. I wrote many versions of Nanami’s story before settling on the one I sent out to publishers.

Q. What challenges did you face in writing a 32-page children’s book after previously publishing a novel?

A. Length! These days it is very difficult to market picture book text that exceeds 1,000 words. And the picture book market in North America is currently extremely tight, making longer picture books for older children especially hard to place with publishers. I knew this would be a challenge from the start, and yet I did not want to shorten the story too much and I did not want to give up on the idea that the story should be illustrated. I love picture books for children ages 6 to 10—picture books with more text and information—and I often wish there were more available. With The Wakame Gatherers, ultimately I cut the text to about 1,700 words then focused on marketing to U.S. publishers that consider multicultural picture books with more words. I was pleased that Shen’s Books was comfortable with the length and the Japanese setting.

Q. Was it difficult to pitch a book with wakame in the title? Did you have to coach anyone on the pronunciation?

A. Actually, publisher Renee Ting of Shen’s Books was adamant about keeping wakame in the title. One of her goals is to bring other cultures to children in the United States, and this includes introducing new words. Different publishers have different approaches, but many picture books published in North America nowadays include non-English words in the text. The glossary in the back of The Wakame Gatherers has a pronunciation guide. Of course many people still mispronounce the word wakame, but it doesn’t seem to be a marketing deterrent.

Q. The book includes a short glossary of Japanese words, an explanation of wakame, and three recipes, which remind me of the extensive companion website for Ash. Was this material part of your initial proposal?

A. Yes, the recipes and glossary were part of my original proposal. I wasn’t sure if they would ultimately be cut. Some publishers like information at the end of a story, others don’t. I’m glad these sections were included though because librarians, teachers and parents have spoken quite positively about them.

Q. Your story portrays Nanami interpreting for her grandmothers from Maine and Japan, a process that sometimes proves difficult due to differences in their backgrounds. Kazumi Wilds’ illustrations beautifully underscore the differences between earring-ed Gram and apron-ed Baachan, and between their respective home landscapes. Yet the book ultimately emphasizes how much they have in common. Was it a challenge to find a balance between acknowledging differences and stressing similarities?

Q. Were there other works of bilingual fiction for children that inspired you along the way? What qualities do you look for in bicultural fiction for children?

A. One of the most poignant books of biculturalism for me was Grandfather’s Journey by Allen Say. The character goes back and forth between the United States and Japan; when he is in the U.S. he misses Japan, and when he is in Japan he misses the U.S. After that book came out, I knew that I, too, wanted to write about that sort of complicated split life from a child’s perspective. There are so few books about intercultural families and precious few set in contemporary Japan. I think their number will increase though; the number of intercultural marriages in Japan has grown significantly and the number of children growing up within two or more cultures has increased as well.

Along the way I’ve been continually inspired by Gary Soto’s poetry and his bold use of Spanish words in his English-language poems and stories (Neighborhood Odes, Chato’s Kitchen). The works of middle-grade authors Linda Sue Park (A Single Shard, When My Name Was Keoko) and Cynthia Kadohata (Kira-Kira, Weedflower) have also inspired me. I hope that we will soon see children’s and young adult writers creating fiction encompassing the Japan-based bicultural experience.

As for what I look for in bicultural fiction for children, I would say authenticity and depth. Many bicultural books for children tend to be rather shallow and focus on obvious surface cultural differences and somewhat predictable stereotypes.

Q. At one point in The Wakame Gatherers, there is an awkward moment for Baachan and Gram when Nanami asks about Baachan’s childhood, which was during World War II. Japan’s experience of that war, especially the atomic bombs, has been taken up in children’s books on both sides of the Pacific—Hiroshima No Pika and Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes come to mind—but The Wakame Gatherers strikes me as unusual in that it ends not with “war is terrible” or “never again,” but with the affirmative daijobu! Did you set out to break new ground in this respect?

A. Gram and Baachan both know from their childhood experiences that war is horrible. Many Japanese and Americans of their generation, even decades later, never manage to get past the residual animosity left from those years of war. I’ve encountered many Japanese and many Americans who carry around decades-old bitterness. Bicultural grandchildren create bridges between people who might otherwise have never held a dialogue. I wanted Baachan and Gram to reaffirm that it is possible to go beyond those painful feelings and that it is necessary to do so for peace. But I did not set out with an agenda to make a particular comment on the war when writing this book. The Pacific War/World War II is simply there, inevitably in the background, as it is in the background of so many bicultural families in Japan. When I ask young children about the daijobu moment in the surf and what it means, they often answer: “It means it’s OK because now the war is done. Now the grandmothers can be friends.”

Q. Amazon.com lists the reading level of The Wakame Gatherers as ages 4 to 8, but its contents and rich vocabulary are appropriate for older readers as well. Have you and your publisher, Shen’s Books, had luck marketing the book outside the 4-to-8 age category?

A. Actually, ages 5 to 10 is more accurate. The character Nanami is about age 8. The vocabulary and the content are geared toward elementary-age children. Sometimes picture books are automatically marketed to the younger set, but in fact picture books are important for older chapter-book-reading children as well as adults. When I visit schools to talk about The Wakame Gatherers I am generally in classrooms from grades 1–5. The book has been included in study units on the ocean, culture, Japan, literature, imagination, story elements and grandparents.

Q. Tell us more about why picture books are important for readers of all ages.

A. Well, certainly picture books feed the imagination and stimulate curiosity and reflection—at all ages. They can also be great learning tools. The books by author/illustrator Shaun Tan (The Arrival, The Red Tree) are examples of amazingly complex picture books. Many of Allen Say’s books also seem directed toward older readers. Satoshi Kitamura’s books have an offbeat wit that appeals to adults as well as children. Have a look at David Macaulay’s books; Ken Mochizuki’s Passage to Freedom or Baseball Saved Us; Lynne Cherry’s A River Ran Wild; Jane Yolen’s many stories in prose and poetry; and David Wiesner’s inventive tales. It seems narrow to relegate the genre of picture books to young children only. There are so many themes and ideas for all age levels that benefit from a creative marriage of text and illustration.

Q. In addition to learning how to gather wakame, you recently spent 18 months researching mikan cultivation for a novel. Your short story “Radio Days,” which appeared in Kyoto Journal No. 68, is set on a mikan farm. How has food and its journey to the table come to play such an important role in your writing?

A. Small farming operations and fishing cooperatives have long fascinated me. I grew up in New England where there are still many small farms even today, and I spent much time in my childhood along the coasts of Massachusetts and Maine. The differences in the approaches to farming and fishing between villages in Japan and the towns I knew in New England intrigue me. The traditional uses of the land and natural resources are starkly different in some ways, yet so similar in others. The food focus is a natural outgrowth of this interest of mine.

Q. What work(s) of fiction and/or nonfiction can your fans look forward to next?

A. I am hoping to be done with my second novel for adults soon and a collection of short stories. And I’m working on a number of different picture book stories and middle-grade novels, even some poetry for children. Most of the works are set in Japan, many inspired by episodes and events experienced while raising my children in Kamakura.

For further information, see Holly Thompson’s website.