March 31, 2006

Otafuku Encounters

by Damon Shulenberger

Author of Otafuku: Joy of Japan (Tuttle, June 2005), Amy Katoh is known for her shop Blue & White, a fixture of Tokyo’s Azabu Juban area for more than 30 years, and three previous books. SWET pried into the profession and persona of one of Japan’' greatest champions of traditional crafts and culture.

Once you start to pay attention, "she" is everywhere—on the doorknob, in the bottom of a teacup, on a notepad or handkerchief, lurking in corners from bathroom-floor tile to the roof-tile finial—a figure known as Otafuku, or sometimes Ofuku, Okame, Otan, or Otayan.  She is the subject of the latest book by Amy Katoh, collector, purveyor, and connoisseur of the simple things in Japanese craft and culture that we want to be part of our daily lives. Author of The Art of Living and Japan: Country Living, and Blue and White Japan, Katoh has lived in Japan for more than four decades. While declaring that "I am not a writer," she has worked with editors, photographers, and designers, producing books that are delicious to look at and read and . . . they keep selling.

She is the subject of the latest book by Amy Katoh, collector, purveyor, and connoisseur of the simple things in Japanese craft and culture that we want to be part of our daily lives. Author of The Art of Living and Japan: Country Living, and Blue and White Japan, Katoh has lived in Japan for more than four decades. While declaring that "I am not a writer," she has worked with editors, photographers, and designers, producing books that are delicious to look at and read and . . . they keep selling.

Q: How did you become interested in writing this book?

AK: Otafuku has been in my life for a long time. I think when I first came to Japan I found that chubby woman who sat in corners and on shelves, just sort of forgotten—no one seemed to know who she was. No shining princess, her down-to-earth charm appealed to me and so I started collecting her because I thought she was a funny-looking lady who laughed all the time—and the more people who laugh all the time the better!

So I had her, but didn’t know why I had her. I think that if you have two or three of things you just have two or three of things, but once you get to four or five it starts to be a collection. When I realized I had eight or nine, I thought, hmm, I’ve got something here, and I wanted to know why I had her, what she was, and what she meant. Eight years ago I tried talking to various publishers about doing a book on Otafuku, and they were just not interested, they didn't think this was something that would sell.

Q: But by that time you had already published a couple books with Tuttle that were very successful, hadn't you?

Q: But by that time you had already published a couple books with Tuttle that were very successful, hadn't you?

AK: I went to some other publishers first, like Chronicle Books and Rizzoli, because I thought it was time to become a little more international. However, my attempts aroused little interest. Finally I went to Tuttle and they said, "Well, we don't really want to do it, but since you've done well on the others, if you promise to do something more commercial after this we'll publish this one for you."

Q: Did they humor you because you said, "I'll pay for this, and I'll take care of that," trying to lessen the risk for them?

AK: None of that. The truth of the matter is they give you an advance on future royalties, but what good is that, it's just money up front. They did give me very minimal expenses, but I wound up having to pay for the photographer, which wasn't really in the game plan, and wasn't something I had done before.

Q: In the book there seem to be photographs from all over Japan. Did the photographer travel around with you in search of Otafuku?

AK: No he didn't. Some of the photos are from Fujita Yōzō,a friend in Kyushu who is a photographer and who takes pictures of Otafuku for me whenever he sees her. Other than that, most of the photographs in the book are of my own objects set in different places, mostly in Tokyo. We did some wonderful things that look as if they were taken in exotic settings, but actually they're just down the road in Minato-ku, of all places. As most longtime Tokyo residents will tell you, there's a lot of history hidden here if you know where to look for it. My husband and I are moving to a neighborhood with a lot of history and there's an old wood and bamboo construction company there that features in a woodblock print by Hiroshige. They've got plastic bamboo for their fence now, so times have changed (laughter), but if you keep your eyes peeled, history is still here!

Q: Before you went to Tuttle, did you start writing things about Otafuku? Did you start from the text end or from the collection end?

AK: Well, I’ve written a diary on and off for years, so there were some Otafuku mentions, but quite scattered—as tends to be the case with diaries. In terms of planning the book, I started from the collection end certainly, and just started telling tales of what I'd encountered, which is something I still do when I have an "Okame encounter."

Q: What attracted you to Otafuku?

AK: She's sort of clumsy and awkward to me and she's not quite all put together. And you know, one of my friends, actually, most of my favorite people, my mother-in-law for one, are like that. She was all put together, but she had this kind of charming imperfection. I prefer people who are that way; I'm not comfortable with people who are fully made up and have all their nails polished and jewels in place.

Q: You included a short poem in the book that seems to embody this: "Even favorably seen / Still an odd sort of figure."

AK: These haiku are all by Kobayashi Issa and there are so many of them. The translations used in the book are not truly mine, but were done for the book. In my mind there was a kind of "marriage" between Otafuku and Issa because they were both able to laugh at themselves and at the foibles of life. They didn’'t take it so seriously. Issa had a lot of pain and hardship in his life but still he was able to find humor in it, to find animation in horses and fleas, the dirty things in life. I think she has a lot of that too, so I wanted to put them together. Ultimately though, it's my own flight of fancy.

AK: These haiku are all by Kobayashi Issa and there are so many of them. The translations used in the book are not truly mine, but were done for the book. In my mind there was a kind of "marriage" between Otafuku and Issa because they were both able to laugh at themselves and at the foibles of life. They didn’'t take it so seriously. Issa had a lot of pain and hardship in his life but still he was able to find humor in it, to find animation in horses and fleas, the dirty things in life. I think she has a lot of that too, so I wanted to put them together. Ultimately though, it's my own flight of fancy.

Q: Did anyone in particular help you understand Otafuku (legends) in more depth?

AK: My friends have helped immeasurably. Sumiko Enbutsu has done a lot. A historian and Japanologist, she is author of Old Tokyo: Walks in the City of the Shogun and Chichibu: Japan's Hidden Treasure, among others, a columnist, and co-author of Water Walks in the Suburbs of Tokyo and she provided historical background and helped coordinate the Japanese and English versions. Another woman, Mari Yamaguchi, a graduate student at Oxford and Keio universities, helped me with research. Professor Ishiguro Hide, who is the head of the University of Tokyo's Center for Philosophy, advised me on the historical/legendary dimensions of Otafuku.

Q: This is your first bilingual book. How did you deal with the translation of your text into Japanese?

AK: Finding the right translator for this material wasn't easy. The first translation had too many problems—it just didn't seem right, so we tried again, but that didn't work out either. Finally we asked a third person, Hiroyuki Shindō, who really isn't a translator, at all, but an indigo dyer. But he seemed to have the right touch, the right sensitivity for my writing, and I think it came out quite well in the end.

It has been a good thing to have the text in Japanese, because there is no book of this nature on the subject in Japanese.

Q: When you talk to non-Japanese who have read your book, do you think they have really got what youōre trying to get across, that the Otafuku idea has transcended cultures in a sense?

AK: That was the question Tuttle was concerned about—they thought it would sell much better here in Japan than abroad. But they've been very surprised at how popular it has been overseas. I've received messages from readers around the world, and at Amazon the other day I noticed it has a good rating! So I’m hoping that in her own quiet way, Otafuku has a message there for anyone to take as they want to.

Q: Was it Tuttle that suggested doing a bilingual edition? I noticed your other books were in English only.

AK: It may have been Tuttle's idea as they thought the only possible market was in Japan. When I think about it, not to have done these books in both languages was really kind of arrogant. I felt much happier we were able to do it this way.

Q: It's interesting, because I think Japanese attitudes towards their own culture have changed in the past ten years. There seems to be a trend, among older people out of a sense of nostalgia, as well as among younger people these days, towards an appreciation of wafū. Not so long ago, if a Japanese were to open one of your books, their reaction to a room with a hibachi made into a coffee table might have been "only a foreigner would do something like that."

AK: Yes, that's absolutely true and the reverse side of that, I am told, is how slightly younger Japanese might put my books on their coffee tables, eliciting remarks from guests: "Ah, Eigo ga dekimasu ka?" So it was a kind of status thing.

Q: So sometimes an idea (like the hibachi mentioned) might not become popular in Japan unless a respected Westerner promoted it?

AK: Through no fault of my own! Funny isn't it!

Q: Could you tell us a little about what it was like to work with your editor on the book?

AK: The editor was Kim Schuefftan. Like most good editors, he's a bit prickly. Indeed, he can be a curmudgeon, but a very knowledgeable and good-hearted one. This is my third book with him, and the first time I cried a lot—this time I didn’t cry once! In fact we laughed a lot. (laughter) At first I wasn’t very confident as an author, so I was intimidated, but I’ve learned to I respect him hugely and I know how to hold out when I think I am right. I think he, too, was in love with our subject. There were times when I was disheartened or discouraged, but he kept that flag flying at all times. This book ever would have happened without Kim.

Q: It sounds like he was more than just an editor. What exactly did he do?

AK: He gave direction and flow and logic to what is really a book of fancy. He gave it backbone and kept the whimsy as well. He did a lot of the rough designing, he loves computers so he’d start mocking up pages and I'd sometimes say, "Kim, we don't need that crazy stuff!" But he did much more than he ever needed to do. As for the writing, he knows I'm too verbose so he cuts and cuts it . . .

Q: I see.

AK: . . . and cuts and cuts it. He’s very good at that, and also making suggestions, for instance "you need something more on this page, so tell us about the philosophy of asobu." I have an odd style of writing that he knows has to be corrected, but he honors my eccentricities.

I know very few people as knowledgeable about Japanese culture and aesthetics as Kim. He has an unfailing eye and a keen sense of the richness of the Japanese craft tradition. He is fascinated by the process of how things are made and the materials used, and he writes about them with a rare sensitivity and unique perspective. It is he who should be writing books on Japan, not I. He goes way back in the editing of books on Japanese art and crafts and many different aspects of Japanese culture. He was involved in the creation of landmark titles about Japan including The Unknown Craftsman and Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art and countless others, like Wada Yoshiko's Shibori Shibori: The Inventive Art of Japanese Shaped Resist Dyeing and Memory on Cloth: Shibori Now.

Q: How did your publishing life begin?

AK: Quite by fluke. I'm not a writer, I'm not a scholar of any kind, I only have curiosity and longevity on my side. Nearly 20 years ago, I had just finished doing a textile lecture series called "A Festival of Fibers," and I was invited to lunch by Patricia Salmon, Pat was one of the modern-day female pioneers who came to Japan in the 1960s and saw what could be done. She started a charm school, she had her own television program, and she owned an elegant antique shop near the Hotel Okura that purveyed Taste, showing how to incorporate Japanese and Chinese antiques into a beautiful style of living. She also wrote a seminal primer on Japanese antiques. More recently she has made her own ahead-of-the-times collection of Taishō era art and artifacts into an eye-opening traveling exhibit called Taishō Chic with an art deco catalog by the same name. This wonderful collection will come back to Japan and be exhibited at the Teien Museum in Shirogane—the perfect venue for it!—in May 2007.

In 1987, Pat said she'd been asked to write a visual book on Japanese antiques, and she was too busy, so she wouldn't be able to do the visuals, but she'd do the writing and would I be interested in doing the visuals? I said well, I'd been doing a lot of photography and styling, so I could do that as long as she did the writing. Somehow we agreed, and about a week later she called and said, "Something else has come up, I'm not going to be able to do that writing after all," and I said "Pat!" (laughter). Just like that, I was an author!

Q: You used your own photographs in your first book, The Art of Living?

AK: No. They’re not my own photographs. I worked with an excellent cameraman, Kimura Shin, who brought light and clarity to what I wanted to portray. I had been working on styling photography for CNN, so that was a good experience. The writing I was more reluctant to get into. But it was very rewarding. I learned as I went along, and writing is something I have always loved to do, but never for public exposure! Surprisingly though, I think the book has had over 15 printings now and it has gotten very good circulation. That was 16 years ago and it is still in print today. I found it one time in South Africa, which really amazed me! It turned out the owner had moved from Tokyo, but still . . .

Q: Patricia Salmon had already arranged for publication of the book with Tuttle, so you didn't have to go around to publishers that time?

AK: That's right, I never had to do that until this time, and I really don't like it—that's really why I stayed with Tuttle in the end. Taking a book around and trying to sell publishers on the idea—for me, hat's a very hard thing to do.

Q: The Art of Living has photographs of so many beautiful traditional Japanese interiors, including your own living room.

AK: Yes, I was fortunate to know a lot of people where were interested in Japanese antiques and art and incorporated them into their houses. The experience of meeting the people in the houses where we photographed and hearing their lives, seeing their love for the different things they had, was an amazing opportunity. It turned out to be a moment in time that perhaps could not happen again. Now I’m grateful to Pat, but at the time—books are such difficult things to do—they’re exhausting. Childbirth is much quicker!

Q: So after you finished that book, were you planning to do another?

AK: No. I was working with Katherine Markulin, a designer and editor from Tuttle and she said, "this one has done so well and it's been so popular, I think it'd be a good idea to do a country-style one." I said "Katherine, you know there's no such thing as country-style in Japan!" But somehow we put it together.

Q: You created a new style.

AK: In a sense we did, although the defining idea, "country style," was a little contrived. Country style is hard to define, but it is a synthesis, an amalgamation of the essences of living in the country—its tools for daily life, its textiles, its food, its pots, into a cloak that identifies,. Is characteristic to, that particular place in the world. It is homespun, it is handmade, it is warn and rich and has tenderness. But any of the books, you could do them again and have a completely different take on the material. I would love to do another "blue and white" book. There is so much material out there, and Japan's blue and white tradition is like no other. But my next book is going to be Japan Pure and Simple.

Q: Will it be coffee-table size, or smaller, like the Otafuku book?

AK: Who knows, but I do like the smaller format. It's only up here (in my head), right now. I know it's a book I want to do but I can't do it now. And I hope that, as with The Art of Living, when I was exposed to those houses by luck, the timing will be right for this next book. It takes a lot of energy, a lot of cooperation from so many people, but it's so addictive—once you've done one (and recovered) you just want to go on to the next.

Q: Since the publication of Otafuku: Joy of Japan last June, where has it been selling most briskly?

AK: In the United States. It’s been in the window of Kinokuniya in New York, I heard, and in the Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C.—lots of people have been telling me they’ve had "Otafuku sightings"! In a museum shop in Fort Worth, Texas, the book was found sharing a shelf with Hello Kitty! When you think of it, Otafuku is an icon, a Hello Kitty, a Mickey Mouse for women. (laughter) Tuttle just told me they're going into the second printing, which is a good sign, though they never tell me exactly how many they publish in a printing.

Q: Did you come up with the design for the cover yourself?

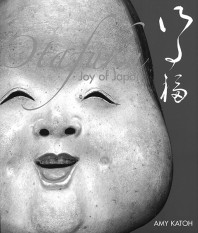

AK: Yes. I worked on it together with Kim Schuefftan and Sophie Gaur, the young Indian/Welsh designer who lives in Australia. We have never met. Kim introduced us. But she grasped the spirit of Otafuku instinctively and gave wonderful life and animation to the design. It is not an easy thing to make a small book like this bilingual. The design can be clunky and using two languages is hard to do gracefully. I just think the Otafuku mask on the cover is so universal that anyone can find joy in that face. It came from the first exhibit, "Happiness," at the Mori Museum in Roppongi Hills, and in that exhibit were more than a hundred Otafuku images, including the scroll 100 Fuku by Masahiro (pp. 13-15) and the mask on the cover.

AK: Yes. I worked on it together with Kim Schuefftan and Sophie Gaur, the young Indian/Welsh designer who lives in Australia. We have never met. Kim introduced us. But she grasped the spirit of Otafuku instinctively and gave wonderful life and animation to the design. It is not an easy thing to make a small book like this bilingual. The design can be clunky and using two languages is hard to do gracefully. I just think the Otafuku mask on the cover is so universal that anyone can find joy in that face. It came from the first exhibit, "Happiness," at the Mori Museum in Roppongi Hills, and in that exhibit were more than a hundred Otafuku images, including the scroll 100 Fuku by Masahiro (pp. 13-15) and the mask on the cover.

Q: In the back of the book you list the names and addresses of some different Okame-related shops.

AK: I wanted to show that it's a living tradition that's still around today. You can still go to the Kabukiza and find little Okame sweets; and you can go downtown and find Otafuku work gloves.

Q: So in a sense, this book doubles as an Otafuku travel guide.

AK: I’ve never thought of myself as a tour guide. (laughter) But yes, people do sometimes visit the shop because of the book and we sell many Otafuku-related things here.

Q: Not all of the Okame in the book are figures; here we have a living example of Otafuku (pointing at a photograph of a smiling old woman looking out a window, p. 109).

AK: That wonderful picture is by Fujita Yōzō, my photographer friend in Beppu who has been photographing everyday life, rice storehouse friezes, and recently has completed a fascinating book on the architecture of stacks of harvested rice straw. He photographs the unseen, the little noticed folkways of Japan—we've been friends for a long time. He didn't say anything at the time, but a young woman came up to him and said, "Fujita-san, look, I found my grandmother in a book! What’s she doing there?" He'd taken that picture of her grandmother and she'd found that picture by chance. It just amazes me, the unexpected connections people find with books. They really have a life of their own.

From Newsletter No. 111 (March 2006)