November 23, 2009

Some Notes on Anthologies

by Suzanne Kamata

According to conventional wisdom, anthologies are a hard sell. Readers supposedly don’t buy them; reviewers are generally loath to review them; therefore, publishers tend to shy away from bringing them into print. Nevertheless, pick up any writing magazine and you’ll probably find a call for submissions to a forthcoming anthology. For example, in the January/February 2009 issue of the American magazine Poets & Writers, anthologists seek poems about bridges in New York City, poems about human rights violations, creative nonfiction about crepes, and poems set in San Francisco. Some of these editors have a book contract in hand, but others are putting together manuscripts with hopes of finding a publisher later—a process that can take years.

Although I am aware of the relative unpopularity of anthologies, I personally enjoy reading them, have written reviews of several, and have contributed to others. I’ve also conceived of, edited, and published three anthologies of my own. None of these books has made me wealthy, but they have been reviewed and have sold modestly well. Would-be anthologists sometimes ask me for advice on how to put together and publish collections of their own. Here it is.

Conception

First, you need an idea—one that is original, but also somewhat obvious. My first anthology, The Broken Bridge: Fiction from Expatriates in Literary Japan, began with a one-page query to Stone Bridge Press, which specializes in books about Japan. Although I had no reputation to speak of, having only published a few stories in obscure literary journals, editor/publisher Peter Goodman liked my idea and had, in fact, been wanting to publish such a book. The concept was not particularly original. I discovered later that at least four other expatriate writers had had the same idea, and three of them contacted Peter after I did. I actually wound up working closely with two—Donald Richie and Leza Lowitz—who recommended and provided contact information for several writers who later contributed stories.

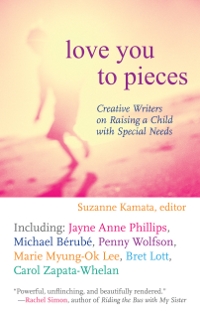

The idea for my second anthology—literature on raising a child with special needs—seems fairly obvious as well. In fact, in the year before Love You to Pieces: Creative Writing on Raising a Child with Special Needs was published, at least four similarly themed collections of essays were published. Mine, however, is the only anthology that includes poetry and fiction on the topic. Quite a bit of time—four years—elapsed between my conception of the anthology and its publication. If I had managed to get my book into print a bit earlier, I might have had a jump on the competition. However, in spite of some similarities to those other four books, Love You to Pieces fills an important niche. It is the first collection of serious literature—writing with an attention to craft—on parenting children with special needs.

The idea for my second anthology—literature on raising a child with special needs—seems fairly obvious as well. In fact, in the year before Love You to Pieces: Creative Writing on Raising a Child with Special Needs was published, at least four similarly themed collections of essays were published. Mine, however, is the only anthology that includes poetry and fiction on the topic. Quite a bit of time—four years—elapsed between my conception of the anthology and its publication. If I had managed to get my book into print a bit earlier, I might have had a jump on the competition. However, in spite of some similarities to those other four books, Love You to Pieces fills an important niche. It is the first collection of serious literature—writing with an attention to craft—on parenting children with special needs.

My third anthology is based on another very timely concept—mothering across cultures. As the United States has just elected its first multicultural president, I sense that more attention will be given to multiracial and multicultural families. I’m sure that if I had not compiled such a collection first, someone else would have beaten me to it. Therefore, although I had been planning to devote my energy to finishing up my second novel, I sent a pitch for Call Me Okaasan: Adventures in Multicultural Mothering to Wyatt-Mackenzie Publishing, an independent American publisher in the Pacific Northwest specializing in nonfiction on motherhood. Because I’d proven myself as an anthologist already, and because I’d racked up quite a few related publications, thus establishing a platform, I didn’t have to produce a manuscript up front. The publisher loved the idea and had faith in my ability to execute it. Within a week, I had a book contract.

My third anthology is based on another very timely concept—mothering across cultures. As the United States has just elected its first multicultural president, I sense that more attention will be given to multiracial and multicultural families. I’m sure that if I had not compiled such a collection first, someone else would have beaten me to it. Therefore, although I had been planning to devote my energy to finishing up my second novel, I sent a pitch for Call Me Okaasan: Adventures in Multicultural Mothering to Wyatt-Mackenzie Publishing, an independent American publisher in the Pacific Northwest specializing in nonfiction on motherhood. Because I’d proven myself as an anthologist already, and because I’d racked up quite a few related publications, thus establishing a platform, I didn’t have to produce a manuscript up front. The publisher loved the idea and had faith in my ability to execute it. Within a week, I had a book contract.

Contributions

Once you have an idea, you need contributions. At the first annual Japan Writers Conference held at Ochanomizu University in 2007, Japan-based writer and anthologist Hillel Wright reported that he sometimes solicited work from writers and poets he’d discovered at open mike events and other readings around Tokyo. If, like me, you live in a remote part of Japan where there are few literary events, this is not a viable option. Many would-be anthologists post or publish calls for manuscripts in publications such as Poets & Writers, or on websites such as Newpages.com. In seeking submissions for my first anthology, The Broken Bridge, I began by writing letters to Japan-based writers of fiction. (This was the pre-Internet age.) I also put out a call for manuscripts in various Japan-based literary journals. Although I expected an avalanche of submissions, my advertisements did not generate enough quality work for a book. Most of the stories included came about from direct solicitations to writers I’d discovered in literary journals, at writers conferences abroad, in publishers’ catalogs, and in libraries. I also made a point of asking contributors for suggestions of other writers whose work might be appropriate. I tracked down one writer—Meira Chand—by posting an announcement in a newspaper.

I’ve found that most writers, even well-established ones at the height of their careers, are generous and cooperative. Edward Seidensticker, Jayne Anne Phillips, and Bret Lott, for example, were all quick to grant permission for me to reprint their works in my anthologies even before I had publishing contracts for the books in question. Some writers (or, more likely, their agents) will inevitably ask about the publisher, the print run, and about who else is included. Others will ask about money. I find this understandable, and I believe that writers should be paid, whenever possible, for their work. Many established writers have neither the time nor inclination to produce original work for free. However, some would be happy to lend an anthologist a piece of writing that has been published elsewhere, and for which they have already been compensated, if the project is of interest.

In my opinion, a good anthology is focused, and yet covers a wide range of viewpoints and topics within that focus. In The Broken Bridge, I aspired to have fiction ranging more or less evenly over the years from post-World War II to the 1990s, written by both men and women, minorities, and several different nationalities. For my second anthology, Love You to Pieces, I sought poetry, fiction, and essays on a range of disabilities, and on children from birth to adulthood, by both mothers and fathers. Since mothers typically take on most of the childrearing duties, it didn’t seem necessary to have an equal representation of mothers and fathers. Because the book was aimed at a multicultural American audience, it was important to include minority writers. Thus, in some cases I favored work by minority or male writers over equally excellent pieces by white women. Since my publisher’s catalog reflects a respect for diversity, my editor agreed with my choices. My third anthology, Call Me Okaasan, includes a more or less equal number of essays by expatriates, adoptive mothers, and women married to men of a different culture. The contributors are mothers of different religions, ethnicities, and nationalities.

Compensation

An anthology is usually a labor of love. Most publishers will not offer to pay contributors or even finance permissions fees for previously published work. In order to pay writers, anthologists generally have to reach into their own pockets. In putting together The Broken Bridge, I was able to avoid hefty fees because most of my selections were from out-of-print books, and the copyrights had already reverted to the authors. This was the case with Edward Seidensticker’s story. Other pieces came from small presses, which tend to request only modest fees. I wound up paying only a few hundred dollars.

In the case of Love You to Pieces, however, I’d started out planning to include an excerpt of Jewel, a best-selling, Oprah-approved novel by Bret Lott. Because the domestic and foreign rights had been divvied up and the novel had been published in several countries, I had to get permission from the book’s British publisher as well as the American publisher. I paid over a thousand U.S. dollars for reprint rights for Lott’s work and for other essays and stories excerpted from books. Keep in mind that writers—and anthologists—must get written permission (which often costs money) for snippets of song lyrics and poetry, also. Fortunately, my publisher paid me a modest advance out of which I was able to cover permissions fees and pay contributors, with a little left over to finance a trip back to the States to promote the anthology in bookstores.

In many cases, however, editors are unable to offer monetary compensation for contributions. As a contributor to several anthologies for which I was paid in copies, I appreciate the intangible benefits of having my work appear in a book. Anthologies are reviewed more often in literary journals or magazines, are sold at both brick-and-mortar and online bookstores, and are bought by libraries. I have heard from more readers who have come across my work via anthologies than from those who stumbled across a story in one of the hundred or so magazines or literary journals where my writing has appeared. Also, I’ve been given at least one well-paying writing assignment based on a contribution to an anthology. As a reader, if I enjoy an essay or story or poem, I often flip back to the contributors’ notes to see what else the writer has published. If that writer has a book in print, I am inclined to seek it out. Therefore, while a famous author’s contribution might bring readers to a book, an emerging writer might attract more readers to his or her work through contributing to an anthology, whether or not there is cash involved.

I received no advance for my anthology Call Me Okaasan, so I was unable to pay contributors for their original essays. However, I allowed the writers to retain rights to their work, which means that they can sell their essays to paying publications. I am also marketing first serial rights (rights offered to newspapers or magazines to publish a manuscript for the first time) to individual contributions, which could potentially generate income for the authors. The writers are also entitled to buy copies at a discount to sell for profit.

Marketing

Now, more than ever, book authors are expected to take an active role in marketing their books. The same is true for anthologists. These days a standard book proposal includes a marketing plan. When my most recent anthology, Love You to Pieces, was under consideration at Beacon Press, I was asked to supply information on how the book could be marketed. I made a list of potential reviewers and probable markets. I also solicited comments via my blog to show that there was an eager readership awaiting the publication of my book when the publisher wondered if anyone would actually want to read it. Presumably Beacon Press, a mid-size independent publisher with a long history, has a reasonable amount of expertise and experience in selling books. Even so, I found that most of the ideas in my report were implemented.

The Seattle-based feminist publisher Seal Press has published a number of anthologies over the past few years. In their guidelines for submission, they suggest that proposals include three niche-marketing areas. I have found this to be useful. If an anthology is too general, it is apt to get lost in the shuffle. If a small, but specific market—or two, or three—exists, it is easier to attract attention. An anthology of poems about bears, for example, might be marketed to nature lovers via wildlife-related publications and national park gift shops; to professors and students of poetry; and to general-interest publications in areas where there are many bears (such as Hokkaido or Alaska). For my first anthology, The Broken Bridge, these niches were Japan, travel literature, and literary fiction. For Love You to Pieces, I targeted parenting publications, magazines and websites focused on disability issues, and universities with disability studies programs. My anthology, Call Me Okaasan, is intended to appeal to readers familiar with my previous books, essays, and stories, and is being marketed especially to mothers, expatriates, and adoptive parents.

Alternatives

All three of my anthologies are published by mid-size independent presses in the United States, and my advice is based on these experiences. Obviously, publishing practices vary by country. (British publishers, for example, don’t seem to be quite so expensive as American ones when it comes to granting reprint rights.)

Also, although I think that much of what I have outlined above can be applied universally, there are other options for getting a book into print. For example, the latest print-on-demand technologies allow editors to compile and publish anthologies with small print runs, little overhead, and little risk. By using the Internet, it is easy to find and market to niche audiences for the most obscure of topics. So while reports from commercial publishers may be bleak, if you have a great idea for an anthology, don’t let bad news stop you. Just don’t expect to get rich.

Originally published in the SWET Newsletter, No. 122 (May 2009), pp. 13–19.

© Suzanne Kamata 2009

American Suzanne Kamata has lived in Tokushima Prefecture for the past twenty-one years. She is the author of a novel, Losing Kei (Leapfrog Press, 2008), and the editor of three anthologies: The Broken Bridge: Fiction from Expatriates in Literary Japan (Stone Bridge Press, 1997), Love You to Pieces: Creative Writers on Raising a Child with Special Needs (Beacon Press, 2008), and Call Me Okaasan: Adventures in Multicultural Mothering (Wyatt Mackenzie Publishing, May 2009). She has also contributed to several anthologies including, most recently, One Big Happy Family: 18 Writers Talk About Polyamory, Open Adoption, Mixed Marriage, Househusbandry, Single Motherhood, and Other Realities of Truly Modern Love (Riverhead Books, 2009) edited by Rebecca Walker.