February 3, 2013

Translating Shiba Ryōtarō’s Saka no Ue no Kumo

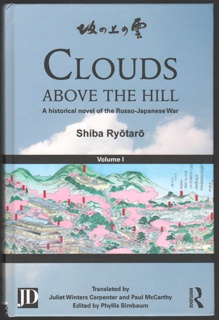

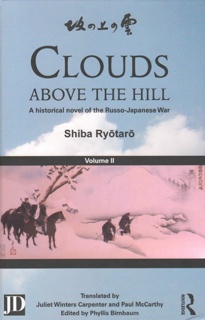

In 2009, translation got underway of best-selling novelist Shiba Ryōtarō’s eight-volume Saka no ue no kumo (English title, Clouds Above the Hill), a planned three-year project funded through Japan Documents, an independent publisher under the direction of Saitō Sumio. The translators are Juliet Winters Carpenter (professor, Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts, Kyoto), Andrew Cobbing (professor, University of Nottingham, U.K.), and Paul McCarthy (professor emeritus of Surugadai University, Tokyo). Two Japanese translators experienced with J-E translation, Takechi Manabu and Noda Makito, also helped with the project as translation checkers. In 2010, SWET asked the translators, publisher Saitō, the two checkers, and Phyllis Birnbaum, editor of the translation, to discuss their perspectives on and experience with the project so far. In December 2012, the first two English volumes were published. Volumes 3 and 4 were published in November 2013.

A review may be found here.

What are the attractions of Saka no ue no kumo as a work of historical fiction?

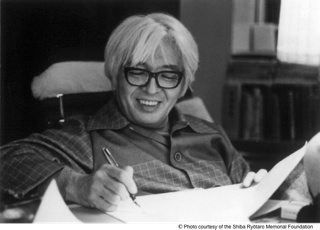

Birnbaum: Saka no ue no kumo is best seen as a history lesson told in the form of a sprawling, mass-market novel. There are fearless military heroes, a trailblazing, doomed poet, scenes from the country and the city, sturdy battleships, brand-new trains, decrepit empires, and a burgeoning modern nation. The eight volumes sweep through a period many people—especially Japanese—know about but can’t be bothered to know about in detail. Shiba Ryōtarō (1923–1996) is well equipped to supply those details and does so with gusto, making the good guys (mostly Japanese) endearing and brave and brilliant, and the bad guys—in particular the Russians—clueless, or worse still, nuts.

This is not an objectively told tale, and readers must come to these volumes prepared to hear the Japanese side of things. Even so, the Japanese side of things is fascinating, and there can be few more entertaining ways to learn about how an isolated, feudal nation emerged into the mysterious world lurking outside, a world closed to most of its citizens for centuries. Shiba is particularly illuminating when he chronicles how difficult it was to shift loyalty from the individual domains, which had been the center of the lives of Japanese during the Tokugawa period, to a new national government far away in Tokyo. That is the strength of Shiba’s novel—he captures well the excitement and the fright of those days.

McCarthy: Shiba’s novel is a popular or semi-popular sort of fiction that finds a wide and appreciative audience in Japan. He is a good storyteller in a traditional Japanese mode, which is rather discursive. He writes historical fiction, with an emphasis on both of those words—tied to history, but not the gospel truth or completely objective.

McCarthy: Shiba’s novel is a popular or semi-popular sort of fiction that finds a wide and appreciative audience in Japan. He is a good storyteller in a traditional Japanese mode, which is rather discursive. He writes historical fiction, with an emphasis on both of those words—tied to history, but not the gospel truth or completely objective.

Saitō: After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the new government that came to power in Japan looked upon the advanced nations of the West as models for the new and modern state they would create. The government implemented policies emphasizing the systems and institutions that had already been established in the governments, industries, and military organizations of most of the leading Western powers. Among their new policies, the Japanese sought to raise the educational level of the populace in order to make optimal use of available human resources and thereby compensate for Japan’s lack of industrial resources. A new system of national compulsory education aimed to educate everyone across the long-established four classes of society (samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants).

The national policy on education nurtured a generation of young people all over the country burning with a passion for learning who were trained to lay the foundations for the industrialization and development of the country. The Akiyama brothers (Yoshifuru, 1859–1930, and Saneyuki, 1868–1918) and Masaoka Shiki (1867–1916), the protagonists of Saka no ue no kumo, belonged to the generation born of this policy. Saka no ue no kumo depicts these figures’ early lives, their passionate aspirations for the future of their country, and the roles they played in its development. All this takes place against a scrupulously drawn backdrop of the society of the period. In that sense, the novel can be considered a valuable chronicle of Japanese society and culture at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.

Cobbing: I think one attraction is the epic scale of the work. Even if it’s not quite on the scale of the Napoleonic conflict tackled in War and Peace, this novel nonetheless relates a key episode in the narrative of Meiji Japan’s growth as a modern state. And the Russo-Japanese War, its main subject, was a major conflict—it was called “World War Zero” in a recent assessment, that is, the war that was one cause of the two world wars to follow. Another attraction is Shiba’s concern for the individual, juxtaposing everyday events within the march of wider historical forces. It’s an effective device to show just how small yet important the individual can be.

As historical fiction, the novel is interesting enough, although I do find some of his characters two-dimensional. The Russian commanders are portrayed as complete idiots, while the Japanese navy in particular is festooned with strong silent types in the mold of Admiral Tōgō, which must have made Japanese readers swell with pride when the novel was published in the 1960s.

Carpenter: This novel tells about the time when Japan was a brand-new country—they had just pretty much thrown out everything after the Meiji Restoration and started to rebuild completely. Eventually Japan found a pretext for challenging China. Chinese soldiers were not very loyal—they didn’t have much nationalist consciousness yet. As this novel shows, Japanese soldiers were bursting with loyalty. Japanese had all just become aware of their own nation. It’s hard for us to imagine today, when Japanese are so peace-loving, what it was like to live in that era when war was “really cool.” They were ready to prove that they could play like “the Big Boys.” They had the best navy—at the time, better than the American navy—and in a very short time, they defeated China. And then they went on to defeat Russia. All this is captured in the wide sweep of Shiba’s Saka no ue no kumo.

What is Shiba’s appeal to Japanese? Why is he so popular? Do you think this book could be popular with English readers?

What is Shiba’s appeal to Japanese? Why is he so popular? Do you think this book could be popular with English readers?

Carpenter: Japanese are very lucky to have an author like Shiba, who has made this history come alive. Shiba is like a cross between the American Civil War novelist Shelby Foote and James Michener, author of long historical novels like Hawaii and Iberia. You can see what Shiba wanted to do—he wanted to craft a work that was about a war, but also wanted to focus on memorable characters from history and bring them forth as vivid human beings. His heroes are the two Akiyama brothers, Yoshifuru and Saneyuki, from Matsuyama, in Ehime prefecture. One brother develops Japan’s modern cavalry and the other builds its navy. They get along well together—they’re not rivals. The great writer Natsume Sōseki (1867–1902) spent a formative year in the town. Masaoka Shiki, the man who revolutionized haiku, was born and brought up in Matsuyama. So right out of this one small town in Shikoku came several eminent figures in the military and literature who went on to have a huge impact on Japanese history.

The novel therefore becomes a story of military valor, but also has surprising literary touches, as even the ailing poet Shiki gets caught up in the thrill of Japan at war. Shiba provides his audience with the pleasure of reading about the courage and ingenuity of the major figures of that era. It is no surprise that this book is so widely read in Japan. Now NHK has brought the novel to even more people with its big new television series. Broadcasting began in 2009 and will continue over the next two years.

Cobbing: I think this book was popular because it appeared in the 1960s during the Vietnam War and shortly after the Tokyo Olympics, when Shiba already had quite a reputation as a writer of historical fiction. So the novel was by a writer people felt they could trust, and it allowed Japanese to feel not entirely negative about their own recent past (well, not all of it anyway). It was a rousing patriotic tale.

Shiba is a good storyteller, but he is hampered because this novel was first written in installments, as part of a long newspaper series. He has to keep reminding the reader of what has already happened, and this makes for much repetition. I get the feeling that since he was writing for a newspaper, he was continually trying to meet deadlines and trying to stretch out his material quite thinly over a long period of time.

Shiba is a good storyteller, but he is hampered because this novel was first written in installments, as part of a long newspaper series. He has to keep reminding the reader of what has already happened, and this makes for much repetition. I get the feeling that since he was writing for a newspaper, he was continually trying to meet deadlines and trying to stretch out his material quite thinly over a long period of time.

But Shiba was good at narrating a human tale so as to appeal very directly to the reader. His sense of humanity is always very evident.

McCarthy: Shiba is regarded as a kokuminteki sakka, a truly “national writer,” by many. This book is centered on the Russo-Japanese War, which many Japanese regard as the last war Japan can, in a sense, be proud of—that is, respect for the enemy, no or very few atrocities apparently, the honor of the warrior maintained, etc. Also, of course, victory for Japan! That’s much more appealing than the opposite.

Saitō: Saka no ue no kumo was first published as a newspaper serial in the Sankei shimbun from 1968 to 1972. Its readers were people who had lived through the harsh experience of defeat in World War II and who were toiling hard to rebuild the country and their own lives. The young protagonists are burning with ambition for their country, and they served well, together with the other prominent figures Shiba introduces, those who led the country in politics, government, and the military as models of hope and strength to the story’s readers.

In the past few years, the media has once again been focusing on Shiba Ryôtarô and his works. Behind this trend are rising worries about the indecisiveness and turmoil in the nation’s government and political leadership. The media has been calling attention to the men of Meiji depicted in this novel because they placed their high aspirations and moral integrity at the service of Japan’s modern state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The epic story of the heroes of that era who staked their lives on winning a bright future for their country has won new appeal in Japan today.

Carpenter: There is a Shiba Ryōtarō Memorial Museum in Higashi Osaka, where they have his house and they show a film about him. You can see his library and his study, just the way it was—also the leafy garden he looked out on as he was writing. The museum showcases over 20,000 of his books, displayed in huge, 11-meter-high bookcases, and in his house are an additional 40,000 volumes or so. When Shiba was researching a topic, he would ask the secondhand bookstores for all the books on the topic and trucks would come up to his house with the books—and he would read them! Plus he used sources in English and other languages, with varying degrees of success, since sometimes the translations that he consulted were not always accurate. There is no doubt, though, that he had a gargantuan appetite for books and knowledge. The museum was designed by the renowned architect Andō Tadao—it’s stunning, well worth a look.

What is your opinion of Shiba as a writer?

Cobbing: I have to say Shiba’s scholarship is dodgy as far as his use of Western source material is concerned. But, as I said before, the work was compiled as a serialized work of fiction published in a daily newspaper. He was writing about the Russo-Japanese War some 60 years after the event, long enough to have acquired some perspective on its significance, and also with a view to placing the “Dark Valley” of World War II that followed in some kind of context.

Saitō: Shiba tried to examine all manner of phenomena from an objective perspective. Committed to the thorough treatment of his subject, he would peruse every possible document or relevant resource—often including interviews with living persons relating to or knowledgeable about the characters treated in the story. He is clearly not a professional historian (although some historians have described Shiba’s distinctive outlook as “the Shiba historical view”), but it is certainly his spirit of service to the reader—to provide a substantial and rewarding reading experience—that has made this work a permanent best seller of over 20 million copies since the start of its publication in book form in 1969.

Carpenter: His works are extremely long and, though gripping, contain repetition. Like many novelists he wrote newspaper serials. An author whose work will be directly published as a book does things differently, avoiding repetition and building a more unified story. In the West, Shiba’s novel would be edited for publication as a book, but in Japan, editors do not make such changes in publishing a newspaper serial as a book. The fact is, Japanese editors of famous authors like Shiba do not dare to touch the text. This is very different from what goes on in the U.S., where they would even edit Shakespeare.

In his frequent digressions, Shiba is reminiscent of a grandfather—“That reminds me of a story,” he seems to be saying frequently. These are charming in their own way but may be very demanding for Western readers.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece War and Peace and Saka no ue no kumo have some similar problems for readers coming to the works via translation. Both books have a huge cast of characters with names that are unfamiliar to most Western readers. That’s a reflection of Russian and Japanese culture, respectively, but a big hurdle for the reader. Like listening to Shakespeare, reading War and Peace is hard at first, but once you allow the story to sink in, you start to appreciate it.

Similarly, Saka no ue no kumo has many names—names of people, places, institutions, ships, military divisions—all of which Shiba seems to revel in listing, time after time. That makes for plenty of names to digest! Hopefully the story will grab people and pull them along.

McCarthy: Shiba is a “representative” Japanese novelist of the late twentieth century He has many more enthusiastic readers than novelists like Kawabata Yasunari or Ōe Kenzaburō, both of whom won the Nobel Prize in Literature; or Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, who should have won it; or Mishima Yukio, who may have died partly of chagrin at not winning it. Personal friends of mine here have been far more excited by my involvement with this project than by anything else I have done (Tanizaki, Nakajima Atsushi, et al.), and invitations to speak on Shiba and his work and its portrayal of Meiji Japan have begun to flow in. Given the wide esteem that he enjoys, I think that introducing his work to a world readership will lead to a much broader and more accurate understanding of contemporary Japanese culture and society than has been the case in the past.

What do you think about the title of the work?

Saitō: Our title is “Clouds Above the Hill.” In English, the images of “clouds” may be somewhat dark, but the image that the author wishes to evoke is that of people filled with aspirations for the future of their country—if you try to express what they meant, it would probably come out something like “Let us at least climb the hill until we reach the clouds, for over them stretches the vast blue sky.”

McCarthy: The problems for the translators begin with the title, in the case of this novel. We all agree that “Clouds Above the Hill,” a literal translation of the Japanese title, may convey too dark an image to the Western reader, who will almost certainly visualize dark, threatening clouds. And since there are occasional allusions in the text to how the tremendous legacy of Meiji Japan was squandered by a later generation of Japanese leaders (i.e., those of the early Showa and Pacific War years), they may feel justified in their interpretation of the title. But most native speakers of Japanese agree that the allusion is to the phrase “seiun no kokorozashi,” literally, “aspiration toward the blue clouds above,” which suggests admirably high ambition in someone.

What other books by Shiba have been translated and how have they been received?

Carpenter: I have translated Shiba before—The Last Shogun. That came out just after Shiba died. I had translated most of the work and was making a list of questions I intended to ask him after I came back from a sabbatical, but it didn’t work out that way since he died before I had a chance to talk to him. (My lesson to translators is—if you have an author whom you plan to ask questions about the original, ask them early!) The Last Shogun, too, was a very interesting project, because it is set at a most dramatic time in Japanese history, just at the end of the Tokugawa period and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration.

The English version was very favorably received, but one complaint that kept coming up was Shiba’s use of brief reconstructed dialogues—non-Japanese readers did question the use of short dialogue interwoven with narrative. Japanese is more comfortable with this technique, whereas in English we prefer one or the other. Such dialogue can be worked into the narrative sometimes while translating, but not always. And if it is always put into narrative, a lot of the flavor disappears.

Another complaint was that he didn’t write more! It’s one of his shorter books. That particular complaint shouldn’t occur with Saka no ue no kumo.

Shiba’s a popular historian and so a translator needs to have as much knowledge of the era as possible. As I would for any translation, I surround myself with books in English and Japanese that shed light on the era—not to the extent that Shiba did, of course, but in a small way. The translator has to be accurate in the use of military jargon and knowledgeable about things ranging from naval strategy to Slavic culture to various dialects of Japanese, which Shiba reproduces. Haiku and other literary bits must be rendered poetically.

It is interesting that Shiba revisited the same era so many times in his writings. It was a time in Japanese history when, as the title suggests, the nation’s aspirations were sky-high. They wanted to build a great country.

Shiba himself had been to war; he was in the army at war’s end, based in Japan. His works, too, were devoted to his country, but he used them to explore serious questions. I remember reading an account by Shiba about a time in the last months of the war when he heard a Japanese officer give an order that would have potentially killed Japanese civilians for the purposes of the military. Shiba was deeply shocked that the once-proud Japanese military would have fallen so low. He devoted his career to the question of why this would happen, digging and digging into the past, the time when Japan was first establishing itself on the world scene.

Saitō: Shiba was a prolific writer whose every book, it seems, has been a best seller. But only a small number of his works have been translated into English thus far, including Saigo no shōgun (The Last Shogun, 1998, trans. Juliet W. Carpenter), Dattan shippūroku (The Tatar Whirlwind, 2007, trans. Joshua Fogel), Yotte sōrō (Drunk as a Lord, 2001, trans. Eileen Kato), Kūkai no fūkei (Kukai the Universal, 2008, trans. Akiko Takemoto), and Kokyō bōjigataku sōrō (The Heart Remembers Home, trans. Eileen Katō). We hope that this is only the beginning of our own English-language “Shiba boom.” The original Saka no ue no kumo is eight volumes in bunkobon paperback, which will be published in four volumes for the initial English edition. Several editors have suggested that if the work can be abridged to about three volumes, it might win a large readership overseas.

Paul McCarthy translated volumes 1 and 3; Julie Winters Carpenter, volumes 2, 4, 5, and 6; and Andrew Cobbing, volumes 7 and 8. Can you tell us something about the mechanics of such a complex collaborative project, which plans to translate an eight-volume work in three years?

McCarthy: As I worked, I had the reliable and experienced Takechi Manabu, who has been engaged in Japanese-to-English translation for more than 35 years, as researcher and consultant. He answers questions about the text, helps us unravel conundrums, and tracks down difficult-to-locate information. I have found his assistance not only a great time-saver but also a life-saver upon occasion, since he can not only answer troublesome points the translators are aware of but also detect points of misinterpretation or inadequate wording in the translation which we may blissfully miss. Sometimes we carry out a lengthy debate by email over the precise meanings of the Japanese original and the optimal English rendering. We try various things until we come upon a solution we both accept—so ultimately it is the translation that wins in the end! The whole process is a stimulating learning experience.

I find it easy to work with Phyllis, our deft and diplomatic editor—with a few bones of contention, perhaps, since her favored style is simpler and more modern than mine.

Birnbaum: The translators submitted chapters one by one, and I did a preliminary edit of those individual chapters. When I got to the end of a volume, I read and touched up the whole volume again. Next I sent the translation, volume by volume, to either Takechi-san or our other Japanese checker, Noda Makito. Takechi-san checked volumes 1 to 6 and Noda-san volumes 7 and 8. Both checkers incorporated corrections or suggestions, along with some explanations, right into the text files. The files then went back to the translators for their review and revision, and then I went over those corrected volumes again. At Routledge, the publisher, a proofreader went over it all, of course, and the translators and I proofread the galleys of the typeset volumes.

What are some of the major problems you have encountered in the translation so far?

Birnbaum: Perhaps the most challenging aspect of editing these volumes has been maintaining consistency in the personal names and titles, place names, military terms, and names of schools, books, hot-spring resorts, mountains, and many other things that appear on every page. If one translator were working on all the volumes, most likely she/he would be consistent in translating certain items over the eight volumes. So, for example, “Tokiwa Society” would never turn up in another volume as “Tokiwa Association,” as it has in these translations. Or “Beiyang Fleet” would never turn into “North Sea Fleet.”

I have devised a way to check on the consistency among the volumes by creating a madly detailed chart of all the personal names, place names, etc. I organized this chart using—among other word-processing functions—the Index function in Microsoft Word. I hasten to add that my chart is not perfect, but I am rather proud of the way I worked it out (and I will be happy to share this editorial device with anyone who might be interested!).

Saitō: The “accuracy” of the translation has been a question we are all concerned about. Although the translators are confident and capable and I do not doubt their abilities in the least, the language (including dialect) and the subject matter in this huge book are very difficult and time is at a premium. I have been persuaded that some readers—especially Japanese—may apply an eagle eye in going over the details of the translation. I therefore decided to ask two Japanese translators experienced with Japanese-to-English translation to check the entire text, as already noted. Since this work is to be published in Japan, moreover, I want to be confident that readings of names, places, and so on, numbers and pronouns, plural/singular, and other basic matters of interpretation are as accurate as possible. Takechi-san and Noda-san did a thorough job and also helped the translators when necessary. I do believe this is a crucial part of J-to-E translation.

Takechi: As Paul said earlier, Shiba is a kokuminteki sakka (popular literature author) and has millions of fans. Japanese readers who are also interested in English are very likely to try reading the English translation, partly to practice their English. They represent a very interested and critical readership, and it is even likely that they will constitute the biggest market for the English edition. My greatest concern, for the sake of the reputations not only of the translators but of Shiba himself, is that there should not be any obvious errors or misinterpretations in the translation. The quality of the translations is very high and I greatly enjoyed my job, but it proved useful to be vigilant, because now and then there were small slips.

Noda: I, too, was greatly impressed by the quality of translation. I encountered a few spots where a critical Japanese reader with Shiba’s original in hand might have quibbles with the interpretation. We checkers can make a significant contribution in identifying the choice of verbs, adjectives, and adverbs that might seem the obvious dictionary definition but that miss the mark either slightly, or sometimes completely, in a particular context. Without reference to the Japanese original, the translation reads smoothly. Still, reading two or three pages of the Japanese original first and then reviewing the translation, I normally came across two or three spots where I thought a different choice of words would be closer to the meaning. It is rare that one can engage in this kind of close reading of a translation, and I found that our work as checkers can be both useful and enjoyable.

Will the differences in the translators’ styles be noticeable?

Birnbaum: There are, of course, some special issues involved in working with three translators. Each translator’s style is different, and that is to be expected. I didn’t intend to make everyone sound the same, and besides that would have been an impossible task. Eliminating each translator’s special voice would certainly dilute the stylish flourishes, and stylish flourishes are what we are looking for! The name of each translator appears on the volumes she/he translates, and so it will be no secret that a different mind was at work on a given volume. I found it fascinating to see how the three different translators rendered the same author’s work into English, and I am hoping that our readers will also find this interesting.

Having said that I did not try to make the translators sound the same, there were certain rhythms in my mind as I read the text, and if I was jarred by a phrase, a colloquialism, a strange tone, I did make changes. I should add that the words of Andrew Cobbing, who is from the U.K., perhaps lost a lot of their Englishness during the editing process, since he is outnumbered by Americans in this translation project.

Given this work deals with China, Korea, and Russia as well as Japan, what did you decide about transliteration of names and words from these other languages?

Birnbaum: We spent a while trying to decide how to romanize Chinese names and words. Most of the histories of the Russo-Japanese War use the Wade-Giles system, even works written recently. This is probably because most historians are familiar with the Chinese place names and personal names in Wade-Giles. Wade-Giles also conveys a “period” flavor. In spite of this, we decided to romanize using pinyin. Shiba wrote the work about 40 years ago, and, when we imagined him telling us his story in English, it seemed more likely that he would have used pinyin. We used pinyin for all place names and personal names except for those, like Port Arthur and Mukden, that are much more familiar to Western readers than the pinyin versions.

We were were fortunate to have the help of Tamara Agvanian, an expert in Russian, who helped us transliterate Russian names and terms into English. This turned out to be quite a difficult task! Tamara searched long and hard through many sources in both English and Russian. HyunSook Yun was a great help with Korean names and terms.

Who is the publisher of this translation?

Saitō: Japan Documents is a small publishing company I head based in Matsudo, Chiba prefecture. For some 45 years, I was engaged in marketing foreign books in Japan (from the Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, MIT, and Cambridge university presses and some 20 others). For many years I worked for a British firm called the Donald Moore Company, arranging for and promoting Japanese sales of books put out by major publishers overseas. The scope of the business later expanded beyond the sales and promotion of scholarly books to bookstores, universities, and corporations to include co-publishing projects, reissuing of out-of-print titles, and other activities. In 1990, we added to our business the translation and publication of important Japanese books and literary classics for scholars and specialized libraries overseas. The first project taken up was Kume Kunitake’s mammoth five-volume journal, The Iwakura Embassy, 1871–73, which we published in 2002. (Kume was the private secretary of Iwakura Tomomi, who led the Japanese mission’s 18-month tour through the United States and Europe.) In 2009, after a two-year process, an abridged paperback edition entitled Japan Rising was published by Cambridge University Press. Saka no ue no kumo is our third translation project.

This project began when I heard in 2003 that the Japan Foundation was in possession of a translation of Saka no ue no kumo completed by the late professor William Naff, of the University of Massachusetts. Later I was able to review one part of that manuscript and to consult a trusted editor regarding its quality. It soon became clear that the manuscript would require considerable revision to make it a readable work of fiction. We initially undertook to edit and revise Professor Naff’s translation. The task, however, proved to be immense and unfeasible. Having spent four years in the attempt, the Japan Foundation decided against going forward with it, and the translation rights were transferred to me at Japan Documents. The Shiba Ryōtarō Memorial Foundation then granted Japan Documents a formal contract to translate the work. In 2008, I decided to have the work translated anew with the collaboration of the three veteran translators and experienced editor present at this roundtable.

The English edition is to be published in four volumes by the U.K. publisher Routledge. Volumes 1 and 2 are currently available and Volumes 3 and 4, the translation of which are complete at this writing, will be published in late 2013. The cover designs for the books are by Anne Bergasse and Kiwaki Tetsuji of Abinitio Design, who undertook the design of the SWET Newsletter from 2005 to 2012. The maps were designed by Komiyama Emiko of Komiyama Printing Company in Tokyo.

Originally published in the SWET Newsletter, May 2010; revised and updated for publication on the SWET website, February 2013.

© Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators