November 1, 2005

On Staying Published

by Kay Vreeland

Publishing a guidebook to Kyoto is a daunting undertaking, so seeing it on bookshelves eight years after publication is gratifying. What is involved in staying in print and in maintaining a relationship with a publisher that is taken over by other presses along the way? Judith Clancy talks with SWET about the process and the rewards of remaining a published author.

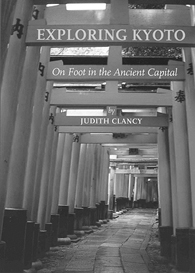

In June 1998, Judith Clancy spoke to SWET Kansai about her experiences as a published author of two books: Naturescapes, a photo book honoring her ikebana teacher, Suiko Tamura; and Exploring Kyoto: On Foot in the Ancient Capital (Weatherhill, 1997), a guidebook of walks through the city. A report of her talk, "An Author's View of Publishing" appeared in Newsletter No. 82 and is on the SWET Web site. Now, via long-distance interview, Clancy offers an update on her ongoing experience as a published author, and as a writer knowledgeable about the culture of Kyoto.

Q: Amazon.com and other booksellers still stock Exploring Kyoto. How does an author manage to keep her book on bookstore shelves for eight years? Do you work with the publisher on revisions? Do you lobby to keep your book out there?

JC: Exploring Kyoto is still on the shelves because the second (1999) printing of 5,000 copies hasn't sold out yet. It is intended, like all guidebooks, to be out there for at least ten years. That's the nature of the publishing beast: a flashy book with lots of photographs intended for the Christmas trade—like the one that was just coming out of Weatherhill when I visited Weatherhill in New York at the time my book was published—will sell a bundle and then disappear.

JC: Exploring Kyoto is still on the shelves because the second (1999) printing of 5,000 copies hasn't sold out yet. It is intended, like all guidebooks, to be out there for at least ten years. That's the nature of the publishing beast: a flashy book with lots of photographs intended for the Christmas trade—like the one that was just coming out of Weatherhill when I visited Weatherhill in New York at the time my book was published—will sell a bundle and then disappear.

My original contract stated that the guidebook would be revised after a certain number of years, at the discretion of the publisher. However, in June 2004 Weatherhill went out of business, its books taken over by different presses. Exploring Kyoto went to Shambhala, with Random House as distributor. This wreaked havoc for a while, but my book is back on the shelves. Although I have been assured that changes can be made, I have had no word on that from Shambhala. Restaurants have gone out of business and fares and fees have predictably risen, something I would like to adjust, but I am not allowed to do this without the publisher's permission. This is frustrating because other guidebooks have been revised, and I am anxious to do so as well.

Q: In your talk to SWET just after the book was published, you said that after submitting your proposed manuscript, you had a long wait until it was accepted. Is this typical?

JC: After I submitted my proposed manuscript, I waited between six months and a year before receiving a boilerplate contract. After the two years of to-ing and fro-ing it took to get the manuscript in shape, I submitted my final version via express mail. The promised first and second publisher's drafts did not wing their way back to me, however. I did not see the book until it was in its final form! That was it—mistakes and all! They must have run out of time dithering over trivia. There were only a couple of months between the final check and my receiving the finished product. Many publishing deadlines are before the Frankfurt Book Fair, the largest in the world, which is held in early October (perhaps to coincide with Oktoberfest?). Most publishers try to have their new wares on display for that occasion. If books are to be translated, this is the venue for making those contacts. Actually, perhaps as a result of the international exposure, a British newsletter about new publications came out at that time highly recommending Exploring Kyoto. I was pleased to receive a copy of this information from my editor.

Q: What was it like working with editors at your publisher?

JC: The former editor at Weatherhill had an interest in developing a series of idiosyncratic guidebooks about Japan, whereas the present publisher acquired Exploring Kyoto when Weatherhill ceased to exist, so the relationship with the current editor—a person I have yet to meet—is cordial but also distant. Previously there was a lot of hard work done via e-mail with the Weatherhill staff, which is no longer there (just like the company itself, which no longer exists except on the spines of its publications). One person was the "China expert," the other the "Japan expert," a fellow who had spent a total of only two weeks in Kyoto during his five-year stay in Tokyo. Neither "expert" was of help; indeed, both were more of a hindrance, asking me repeatedly to recheck kanji and their Japanese readings. (Originally, all of the maps and chapter titles had kanji beside the English names, so a tourist might hold the book up to someone, such as a taxi driver, and just point. All this was removed without letting me know!) I was asked a lot of foolish questions that took up valuable time, which I resented, but I figured that if they (the "experts”) were asking, then the general public might have the same questions, so I answered as quickly and thoroughly as possible. Eventually, I also met the Japanese member of the staff, a very young OL-type who didn't know a thing about her country, much less about Kyoto and its culture. I suspect that she was behind some of the time-consuming questions I got.

Then there was the initial promise of my seeing the first, then the second draft before publication. I saw neither!!! I sent in, via express mail, the last text corrections, and I heard nothing until I got the book, mistakes and all. What a shock that was! There were mistakes that two readers and an editor-friend had missed, so I must take credit for some of them, but 90% are Weatherhill's. I sorely wished that I had gotten a look at the first draft. The publisher was rushed, but a lot of time could have been saved if there werent so many unnecessary questions and checks. I wish I could give good advice on how to work best with an editor, but big publishing houses have tremendously busy schedules, with several authors, printers, and accountants calling for advice and information all at once. There is so much going on that one has to be patient while persevering.

Q: The book is still widely available, so perhaps the publisher made up for the initial snafus with excellent advertisement and distribution?

JC: Alas, the after-publishing horror stories were in the same vein as the pre-publishing ones, and all due to lax distribution. If I appeared on TV or in a magazine, I would notify the publisher that there might be a surge in Japanese sales and to make sure there were books available. However, I remember when the 1997 conference on the Kyoto Protocol took place in Kyoto, I practically had to carry the books out to the International Conference Hall myself, since Weatherhill depended on its local distributor, and distributors make no note of such gatherings in relation to sales or tourism. This continues even now, and I still have no advice on how to counter it. Since I am not in the league of best-selling authors, I can understand the distributors' dilemma, but because they have little idea what books they are handling, the connection between timely events and sales is nil.

I called newspapers and magazines and advertised myself; in fact, I advertise Exploring Kyoto in the Kyoto Journal. Waiting for the publisher to do anything meant a lot of teeth grinding and lost opportunities, so I handled all my post-publishing publicity. I mentioned in my talk that one needs a strong ego to write a book; this is one of the reasons why.

Q: Do you think there is something writers can do in the original contract to protect themselves when the publisher goes out of business?

JC: There is nothing writers can do to protect themselves. The publisher doesn't want to go out of business. When it must, interested parties will buy up the stock. However, with today's desktop publishing, authors might stipulate that they gain the right to continue to publish the original manuscript if their book is remaindered. Once the factual information itself is in the public domain, it belongs to the world, and unless it is a formula or patent, it cannot be "protected" from use by others, since such factual information would too easily fall under "fair use" in copyright law. Being able to continue publishing the book oneself would be a way to "keep" it.

Q: Looking back over your long association with your publisher, what do you wish you'd "known then that you know now"?

JC: Every situation is different. Every book has a niche market; many publishers are hard-working people, but they are people who do not have all the answers, only the expertise their experience has brought them. The author's strength is in knowing that everything written will be challenged by the editor. Arriving at a good working relationship with your editor is essential. Professional behavior is a key.

Otherwise, I wish I had known there was a Japanese twenty-something OL in the office while I was getting zany requests for fact confirmation. If I could have spoken directly to her in Japanese, I would have been far less frustrated. I think the other staff, none of whom spoke Japanese, trusted her shaky word over mine. This wasn't sorted out until after publication.

I also should have taped my refrigerator door shut, because many a time, when I couldn't find a word or confirm a fact, I would look into the refrigerator and pull out something to eat, hoping that while munching away, the muse for guidebooks would enlighten me. Needless to say, I gained weight waiting for the requisite phrase to leap onto the text.

Q: What advice would you offer an aspiring writer of non-fiction books about Japan? Find an agent (how?) or go directly to publishers?

JC: Agents . . . I think it is easier to approach a publisher directly. When writer-agent matches are made, in my experience, agents find the author after a newspaper or TV interview. In my case, I prepared three chapters of my book after having two different friends read for me and having another friend edit and check for factual errors. With that done, I began sending the packet to the publishers of books on Asia. There is this crazy catch-22 that requires one to have a book manuscript already finished, but then to completely redo it if need be. It is very frustrating and discouraging in the beginning, finding this balance between compliance and belief in one's knowledge. I suppose the only other advice I can offer to those interested in writing is to form a group where others can read for you and you for them, and where still another will offer to edit your work. Editing is a very special skill, one that remains under-recognized, I think, because so many writers believe that they write quite well.

I am reading the autobiography of Dirk Bogarde, an elegant and extremely articulate writer. I was impressed by his response to one letter from his publisher, which gave him special pleasure because he sensed "a ribbon of managerial approval" ran though it. Having that approval is a kind of divine intervention. Everyone struggling to put thoughts on paper would love to receive that kind of response to his or her work.

Q: What is the best part of writing and publishing a book? What "tricks of the trade" can you offer (i.e., your earlier advice on making one's own style sheet)? Any advice for getting over the hard parts smoothly?

JC: The best part of being published is the recognition it brings. The wonderful satisfaction and sense of accomplishment must rival stepping offstage after a good musical performance. The high it brings, and the pride in oneself, are among life's special gifts, at least for me. By getting published, you prove to yourself and others that you can do the research, follow through on a commitment, and produce something of worth. The hard parts appear quite regularly and unexpectedly, and you cannot avoid them—sort of like raising teenagers, I imagine. You just have to endure with determination and a strong willingness to take criticism, and remain focused.

JC: The best part of being published is the recognition it brings. The wonderful satisfaction and sense of accomplishment must rival stepping offstage after a good musical performance. The high it brings, and the pride in oneself, are among life's special gifts, at least for me. By getting published, you prove to yourself and others that you can do the research, follow through on a commitment, and produce something of worth. The hard parts appear quite regularly and unexpectedly, and you cannot avoid them—sort of like raising teenagers, I imagine. You just have to endure with determination and a strong willingness to take criticism, and remain focused.

I made my own style sheet for the book, since it helps an author to behave like a copywriter in handling organizational elements such as special symbols, dates and numbers, map and diagram style, a list of words and terms used and their forms, and so on. My style sheet eventually acquiesced to the one Weatherhill used for the published book. Once under contract, a publisher usually will tell you about their style of editing.

My personal style sheet mostly concerned place names and the spelling of Japanese words, as one might expect when doing a book containing foreign words. Then there was my attempt to keep everything in third person, and to avoid inserting my own opinion when stating different facts about a place. The most difficult thing was to try and find suitable words to describe some of the most beautiful gardens and statuary on earth, without being repetitive. This was a big problem, especially since 17 of the places are World Heritage sites. If it had been a fictional work, I might have played around more with words, but instead I decided to remain prosaic and practical, since the book would have to be understood by people of different nations, many of them not native English speakers. The style sheet also helped me keep track of the "fudge factor"; i.e., when in doubt about differences between a legend and historical fact, I put in both accounts.

Generally, I follow the Chicago Manual of Style, because it is the one I have, and my Random House dictionary.

How to navigate the hard parts smoothly? There is not much I can say here, except to believe in yourself and the need or market for a book such as the one you are writing. Lots of people will discourage you. You have to take this in stride and keep trying.

Q: Has the guidebook been translated? Have you made much in royalties?

JC: Originally, and innocently, I had hoped to have the book translated into Chinese and Korean, the languages used by the two biggest groups of tourists who visit Kyoto. However, acquiring the rights to do so would have cost more than publishing houses in either China or Korea could afford. Understandably, they would rather have sent their own people to Japan to do the writing. Right now, a Japanese friend's daughter and her new German husband are under contract by a German publishing company to do a guide in German, and I suspect that much of my information will appear in that guide.

Royalty-wise, I have recouped the money I spent visiting temples and traveling around the city, but when sales dip, my royalties halve, which is not something I look forward to. Only best-selling authors make money from books.

Q: What writing projects have you seen bear fruit in connection with your first guidebook, since speaking to SWET in 1998?

JC: Originally, I wanted to do another guidebook to Nara and Shiga, but the publisher was not interested, saying there was no market for it. Of course, Prime Minister Koizumi’s recent "Yōkoso! Japan" campaign has encouraged thousands of tourists to visit, so the shortsightedness of that response still galls. More than ever, people would like information on the city and its environs; efforts to provide this information are being made by a variety of organizations, but it is piecemeal and spread out all over the Net, or on individual blogs with little significant research behind the information. This is frustrating to behold.

Regarding other projects related to Exploring Kyoto, I now teach a tourist guide course to Japanese who are preparing for the new Kyoto Tourist Guide Proficiency Examination, and I was pleased to learn that several women credited their passing grades to studying with me. That was very gratifying, since I am teaching Japanese about Japanese culture and history. I also am asked to write for magazines occasionally and did a long article about kaiseki food and famous Kyoto restaurants that was translated into Spanish for a Mexican publication.

Q: What new projects are you working on?

JC: Right now I'm working on a book of restaurants in Kyoto, particularly those of special architectural interest. No publisher is in mind, and I may eventually self-publish, because I believe such a guide is needed. I will start knocking on doors when I am done. Having two books behind me gives me a bit of confidence and makes a nice calling card. Starting out on this third book, in an area in which I still have much research to do, makes me feel unsure of getting published, even though I know of the need for such a publication. So much can happen between all the thoughts flying around in my brain and good solid text, but I will commit myself to completing it and hope for the best. Even if I don't get published, I will have gained a great deal of knowledge, and this in itself is gratifying, but I may also gain some unwanted kilograms, which is less so.

From Newsletter No. 109 (October 2005)