Howard Hibbett (1920–2019): Scholar, Translator, Editor

Howard Hibbett's name was not familiar to the general public, but among Anglophone scholars and students of Japanese literature it was very much one to be reckoned with. His contributions touched us in a variety of ways; many of them extended our understanding of Japanese culture in new directions, and virtually all of his work—be it as a scholar, a translator, a critic, or an editor—was of the highest standard.

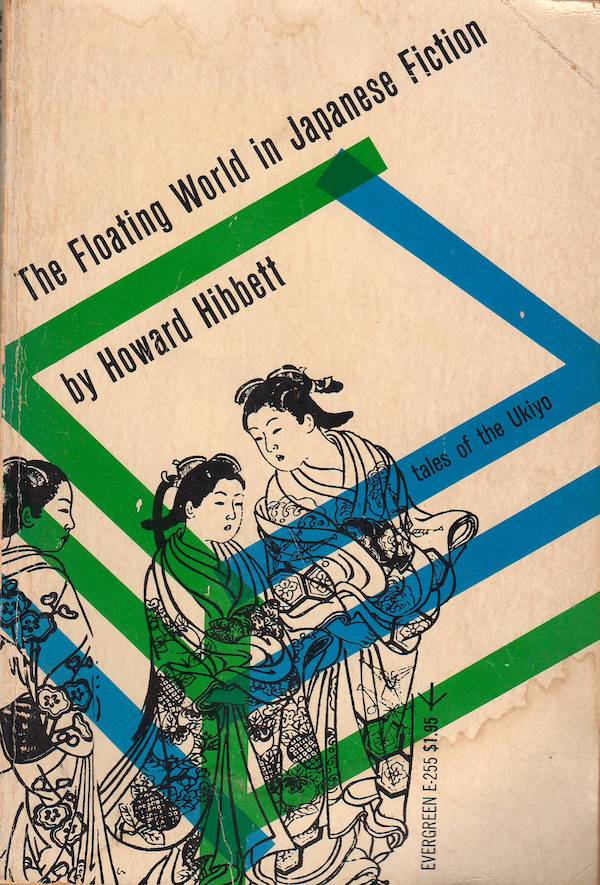

Probably he was most widely known as a translator, especially for a series of novels, novellas, and stories by Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, which played a major role establishing Tanizaki's stature among non-Japanese readers not just as one of the major Japanese writers of his time but as a figure of worldwide significance. His scholarly works were notable for revealing the riches on offer in areas that had largely been disregarded by previous researchers and translators. The Floating World in Japanese Fiction (1959) was a tour de force that showed future generations of scholars that it was possible to make the dauntingly intricate popular prose literature of the Edo period accessible to a non-Japanese audience. Few if any of us, alas, have been able to approach this project with anything like the kind of panache, the apparently effortless elegance of expression that he seemed to have at his command at all times. The same qualities were very much in evidence in his classic study of Japanese humor, The Chrysanthemum and the Fish (2002), a work of consummate erudition worn with such lightness and grace that it can easily be read for pleasure alone.

Probably he was most widely known as a translator, especially for a series of novels, novellas, and stories by Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, which played a major role establishing Tanizaki's stature among non-Japanese readers not just as one of the major Japanese writers of his time but as a figure of worldwide significance. His scholarly works were notable for revealing the riches on offer in areas that had largely been disregarded by previous researchers and translators. The Floating World in Japanese Fiction (1959) was a tour de force that showed future generations of scholars that it was possible to make the dauntingly intricate popular prose literature of the Edo period accessible to a non-Japanese audience. Few if any of us, alas, have been able to approach this project with anything like the kind of panache, the apparently effortless elegance of expression that he seemed to have at his command at all times. The same qualities were very much in evidence in his classic study of Japanese humor, The Chrysanthemum and the Fish (2002), a work of consummate erudition worn with such lightness and grace that it can easily be read for pleasure alone.

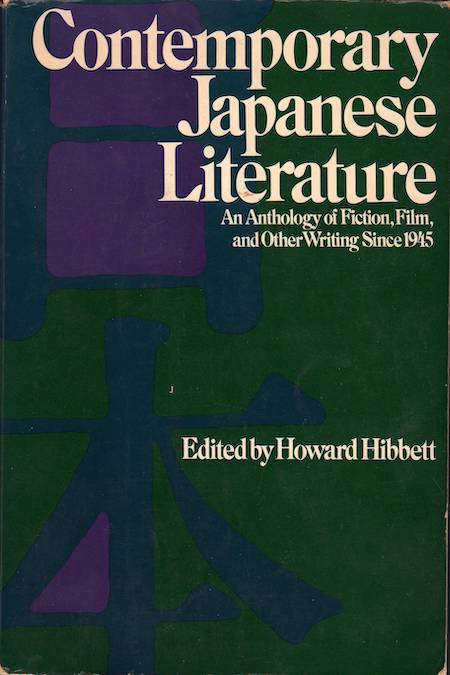

Another ground-breaking achievement, especially for its time, was his compilation of the 1977 anthology Contemporary Japanese Literature, one of the first collections to show Anglophone readers how far the vitality and variety of Japanese fiction and poetry extended beyond the relatively few big names that had already become familiar in the postwar era. Among the notable features of this collection was his decision to include the screenplay for Kurosawa's Ikiru, highlighting the importance of film as an integral component of Japanese literary as well as visual culture.

A less visible and probably more time-consuming editorial role was his service as editor-in-chief of the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. A colleague recalls: "As the HJAS editor for decades he was amazing to watch at conferences. He went to panels from morning to night and if he particularly liked a paper, he’d speak with the panelist and ask for a manuscript. He spent as much time on the Chinese side as the Japanese... He was extremely serious and tireless, and he took notes assiduously. I once asked him what he did with those accumulated notes he was constantly taking on those small memo pads. He smiled and said he had them all filed but never looked at them again."

Apparently, he was also blessed with an unusual talent for making editors happy. A piece that he contributed to the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan project supposedly led the editor-in-chief, Gen Itasaka, to comment that among all the contributions submitted by hundreds of authors from around the world, Hibbett-sensei's was the only one that required no editing whatsoever.

For more than a few American college students of Japanese, though, the first awareness of Hibbett-sensei's existence came through his role as co-author of "Hibbett and Itasaka,” the textbook known officially as Modern Japanese: A Basic Reader (1965). The notion that an elementary Japanese textbook might accord priority to reading rather than conversation may seem little short of outlandish now, and undoubtedly it seemed so to more than a few observers even then. For some of us, though, the opportunities that it provided to observe what the Japanese language could do in the hands of a Natsume Sōseki, an Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, or a Shiga Naoya, and to begin to see how it worked as a medium for presenting a broad range of cultural and social philosophical concepts, proved to be an unforgettable experience.

For more than a few American college students of Japanese, though, the first awareness of Hibbett-sensei's existence came through his role as co-author of "Hibbett and Itasaka,” the textbook known officially as Modern Japanese: A Basic Reader (1965). The notion that an elementary Japanese textbook might accord priority to reading rather than conversation may seem little short of outlandish now, and undoubtedly it seemed so to more than a few observers even then. For some of us, though, the opportunities that it provided to observe what the Japanese language could do in the hands of a Natsume Sōseki, an Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, or a Shiga Naoya, and to begin to see how it worked as a medium for presenting a broad range of cultural and social philosophical concepts, proved to be an unforgettable experience.

Finally, I would like to note with appreciation that all of the other demands on his time notwithstanding, Hibbett-sensei was not one to stint when it came to taking care of his students, both present and former. I recall his mentioning while he was serving as director of Harvard's Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies in the mid-1980s, before computers made it so much easier to compose and send off recommendation letters, that he devoted every Friday to this task. I wonder how many of us could say as much.

(Joel Cohn, now retired, studied under Howard Hibbett at Harvard University, 1975–1984, and taught Japanese literature at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures. For details about Professor Hibbett’s career, please see the Harvard University obituary.)

(Joel Cohn)

Originally written for the Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators, May 12, 2019.

Comments:

There are no comments for this article yet.

Add your comment:

If you are a SWET member, log in to post a comment immediately. Comments are moderated for non-members.