Kim Schuefftan (1936–2021): Editor, Writer, Collector

By the time SWET was founded in 1980, Kim Schuefftan had already been an editor at Kodansha International (KI) for 14 years. Then in his mid-forties, he was one of only a handful of senior editors in the flourishing English-language book publishing industry in Japan.

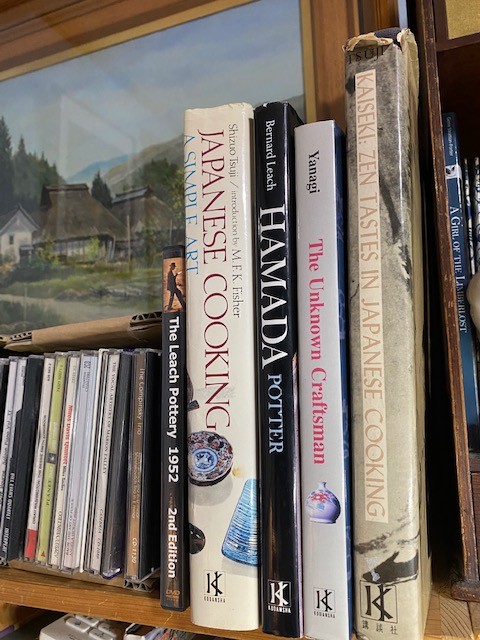

Schuefftan was hired by KI in 1966, and he put his writing skills and knowledge of art and craft to work on a variety of books, from those culled from the parent company’s extensive backlist to new acquisitions. Most of the latter books required considerable development and adaptation to present often complex and nuanced Japanese concepts to a Western audience. He knew how to do them justice without “dumbing down.” Even books translated from the parent company’s back list required extensive reorientation. Schuefftan worked on many groundbreaking titles that not only helped establish KI’s reputation but also introduced new facets of Japanese culture to the world, including Kaiseki: Zen Tastes in Japanese Cooking (1972), The Unknown Craftsman (1972), Hamada Potter (1975), Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art (1980). Many of these are still in print today.

Schuefftan was hired by KI in 1966, and he put his writing skills and knowledge of art and craft to work on a variety of books, from those culled from the parent company’s extensive backlist to new acquisitions. Most of the latter books required considerable development and adaptation to present often complex and nuanced Japanese concepts to a Western audience. He knew how to do them justice without “dumbing down.” Even books translated from the parent company’s back list required extensive reorientation. Schuefftan worked on many groundbreaking titles that not only helped establish KI’s reputation but also introduced new facets of Japanese culture to the world, including Kaiseki: Zen Tastes in Japanese Cooking (1972), The Unknown Craftsman (1972), Hamada Potter (1975), Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art (1980). Many of these are still in print today.

In 1989, after 23 years at KI, Schuefftan became a freelancer. His veteran eye was widely respected, and editorial assignments were soon forthcoming. He was editor of Ikebana International’s three-times annual magazine, wrote for ANA’s inflight magazine Wingspan, and provided editorial services for the International Society for Educational Information, among other clients. He also continued to edit the manuscripts of individual authors and was instrumental in seeing a number of new works published.

Among wordsmiths who contributed to the English-language writing community in Japan, Schuefftan was a memorable figure. He possessed deep technical and aesthetic knowledge of crafts and art, which he also collected with great enthusiasm—pottery, rugs, textiles, ethnic curiosities. He was curious and conversant in many fields. His advice and professional help were sought for projects relating to crafts, music, food, traditional culture, and more. He could be charming, gracious, and generous. Memorably, his humor leaned toward the droll and purposely nonsensical. He was known for opening his conversations with a piece of random whimsy calculated to elicit a chuckle and tear the listener away from whatever humdrum had preceded it. At times, he could be demanding, and he sometimes clashed with colleagues and authors over the content of a manuscript. He rewrote texts to his own muse.

Among wordsmiths who contributed to the English-language writing community in Japan, Schuefftan was a memorable figure. He possessed deep technical and aesthetic knowledge of crafts and art, which he also collected with great enthusiasm—pottery, rugs, textiles, ethnic curiosities. He was curious and conversant in many fields. His advice and professional help were sought for projects relating to crafts, music, food, traditional culture, and more. He could be charming, gracious, and generous. Memorably, his humor leaned toward the droll and purposely nonsensical. He was known for opening his conversations with a piece of random whimsy calculated to elicit a chuckle and tear the listener away from whatever humdrum had preceded it. At times, he could be demanding, and he sometimes clashed with colleagues and authors over the content of a manuscript. He rewrote texts to his own muse.

Even before arriving in Japan, Schuefftan led an interesting life. He grew up mostly in California among artistic types. Many of his parents’ friends, and some family members, were artists and musicians. His parents ran a workshop that produced ceramic figurines in the Santa Monica, California area. It was there that he received a solid grounding in clays, kilns, and craft. He attended the Ojai Valley School in his elementary years. In his teens, his mother remarried, and at 16 he traveled to Israel and spent four months in a kibbutz. Despite his Jewish upbringing, he realized that Israel and the kibbutz lifestyle did not suit him. He developed a streak of defiance against strictures of any kind—religious or otherwise—that followed him throughout his life.

Later, he entered Reed College in Portland, Oregon, initially as a biology major but he found the sciences unpalatable. He later entered the University of California at Berkeley, where he studied cultural anthropology. His love of music over a broad spectrum—from jazz and blues, folk to madrigals, to Baroque to opera to Prokofiev—flourished in this stimulating university community. That love must have helped him get a part-time job at a record shop on Telegraph Avenue, where he learned even more from the veteran keeper of the shop.

After graduating from UCB, adventure took Schuefftan to Tokyo. There, he attended International Christian University, intending to study Japanese. His interest soon strayed from his ongoing studies to the real world. He landed a coveted position at NHK as a writer and editor. In hopes of getting a children’s book he’d written published, he went to Kodansha International, founded three years earlier, and ended up getting a job offer in addition to a publishing contract. (See also “Kim Schuefftan and the Heyday of Culture Books,” based on a talk given by Schuefftan to SWET in 1999.) He enjoyed the firm confidence of executive director of KI Nobuki Saburō (see SWET Newsletter, No. 118) and worked with many of the Japanese and non-Japanese editors still active today.

In 1990, he and his partner, artist Sekiji Toshio, moved to Shimonita, Gunma prefecture. There, in an old farmhouse deep in the hills, he lived the free life of a “remote” professional long before the coronavirus pandemic came along to free many more of his colleagues from the office. He traveled to Tokyo regularly to tend to business, stock up on books and CDs, and shop for some of his favorite foods. Equipped with a computer, an Internet connection, and low-cost telephony, Schuefftan continued to support himself by editing, rewriting, and writing, often under pseudonyms. In the autumn of 2018, at the age of 83, Sekiji suffered a near-fatal accident and he moved into an assisted living facility. Schuefftan was left without his best friend and partner of four decades.

Earlier, Schuefftan had formed a close friendship with author and Japanese food expert Nancy Singleton Hachisu, a resident of the nearby Kodama area of Saitama. He provided advice on writing and handling of photographs for her books. As the challenges of age undermined Schuefftan’s freewheeling lifestyle, Hachisu gradually began extending various kinds of help. With her support, he moved out of the increasingly dilapidated minka and into a comfortable old-style house in Kodama. There, he lived happily for a year and a half with his three cats, continuing his work, puttering in the garden, and enjoying the society of friends and acquaintances. He considered himself fortunate to have someone close at hand to advocate for him when he was hospitalized, deal with the Japanese senior care system (kaigo), and arrange the other details his condition required. When his heart finally gave out, he was at home, with his cats to comfort him and friends living nearby.

Kim Schuefftan passed away on May 22, 2021. He was eighty-four.

SWET invites memories of Kim Schuefftan to be added in the Comments section below.

* * * * * *

Books Edited by Kim Schuefftan (selected titles) and articles/interviews available online

Kodansha International/Kodansha America

1967 The World of Japanese Ceramics, by Herbert H. Sanders

1970 Zen Painting, by Awakawa Yasuichi, John Bestor, trans.

1971 Zen and the Fine Arts, Hisamatsu Shin’ichi

1972 Kaiseki: Zen Tastes in Japanese Cooking, by Kaichi Tsuji (Tankōsha and KI)

1972 Unknown Craftsman, by Yanagi Sōetsu

1974 Arts of Korea, by Kim Chewon

1975 Hamada: Potter (1st edition)

1978 Washi: The World of Japanese Paper

1980 Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art. Shizuo Tsuji (KI)

1983 Shibori, Wada Yoshiko, Mary K. Rice, Jane Barton

1990 Living National Treasures of Japan, by Barbara Curtis Adachi

Other

1985 Backstage at Bunraku, by Barbara Curtis Adachi (Weatherhill)

1990 Japan: The Art of Living, by Amy Sylvester Katoh (Tuttle)

1996 Japan Pure and Simple, by Amy Katoh (Tuttle)

2005 Otafuku, Joy of Japan, by Amy Katoh (Tuttle)

2005 Japan: Country Living, by Amy Katoh (Tuttle)

2012 Japanese Farm Food, by Nancy Singleton Hachisu (Andrews McMeel)

2015 Preserving the Japanese Way, by Nancy Singleton Hachisu (Andrews McMeel)

Online publications

Blog post about pottery and clays

Kagoshima: Just Art Wingspan article (PDF)

Received from friends of Kim Schuefftan:

Filmmaker Marty Gross, an old friend, let us know that he posted an obituary, along with some photos, at the Leach Pottery website https://leachpotteryblog.com/2021/06/02/kim-schuefftan-former-arts-editor-at-kodansha-international-publishers-has-died/

Excerpt:

Kim was the editor of The Unknown Craftsman by Yanagi Soetsu and Hamada: Potter by Bernard Leach, both essential texts in the history of the Mingei Movement and The Leach Pottery. He was also responsible for important books on New Mexico potter Maria Martinez, and many more on Japanese textiles and cuisine.

He was not the author but he was the driving force behind the preparation, design and realization of these works. The books Kim Schuefftan worked so hard on had a profound and lasting impact on thinking about crafts in the 20th century and beyond.

During his long career in Japan Kim maintained passion for his work and for crafts. He could be cantankerous and prickly while trying to get everything "just right” but his commitment to crafts was unwavering. He regularly got into trouble with his publishers for overspending, especially when he insisted that the two books by Yanagi and Leach be finished with handmade “momigami” paper covers and handscreened with Japanese lacquer.

Bernard and Janet Leach had long associations with Kim Schuefftan who helped them in many ways during their visits to Japan. It was Kim, I believe, who suggested that Bernard write Hamada: Potter as a tribute to his great friend. In 1973 Kim visited St Ives to work with Bernard on the editing of Hamada: Potter. With Bernard’s eyesight failing, Kim read passages of the text aloud and suggested revisions as part of their editorial collaboration.

On this same visit to St Ives, using a Super 8 movie camera for the first time, Kim filmed scenes of the activities at The Leach Pottery. Several years ago he gave me this unseen footage from which I made a new film, adding commentary by John Bedding. We call this film, A Visit to The Leach Pottery, 1973. Kim became very emotional upon hearing that the film was shown online as a special presentation during the 100th Anniversary Celebrations of the Leach Pottery last year.

Kim cherished the memories of the years he spent working with Janet and Bernard and felt they were a highlight of his career.

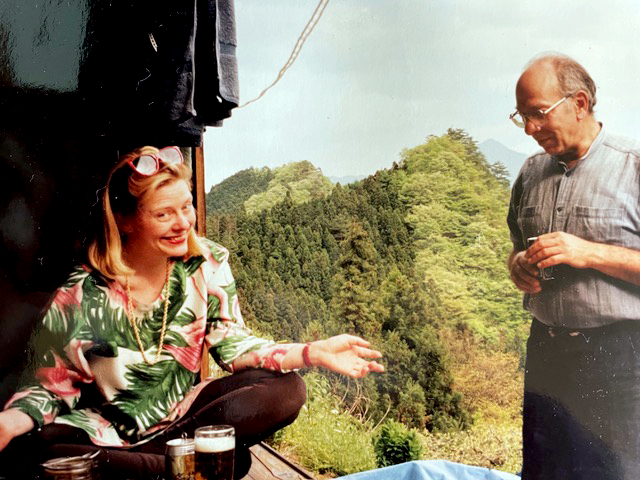

In 1973 Kim encouraged Bernard and Janet to visit the small lacquer-making town of Wajima on the West coast of Japan. Presented here are photographs from that trip along with two more recent photos.

(from email to SWET received June 6, 2021)

* * *

Received from Margaret Price, Gold Coast, Australia, August 5, 2021:

In the beginning was a grandmother

And she said to God, ‘Lissen, make some soup.“

And God created a vast aqueous orb and placed it in the firmament.

And the grandmother said, “This is soup? It’s too watery.”

And God called forth creatures great and small, the fish and turtle, the leviathan and planktonathan, the gefilte and kamaboko.

And He created the land, the continents, crags and canyons, atolls, archipelagos and peninsulas. And He peopled these with people and panthers and penguins and gnats.

And said the grandmother, “That’s better. Now heat it up.”

So God created the fire of the sun and he sprinkled the heavens with lights great and small.

And the grandmother rejoiced. “Not bad, not bad. A little fancy, maybe, but more like it. So now we got days, we gotta call the first one New Year.”

And that is how the custom of having soup at the New Year originated.

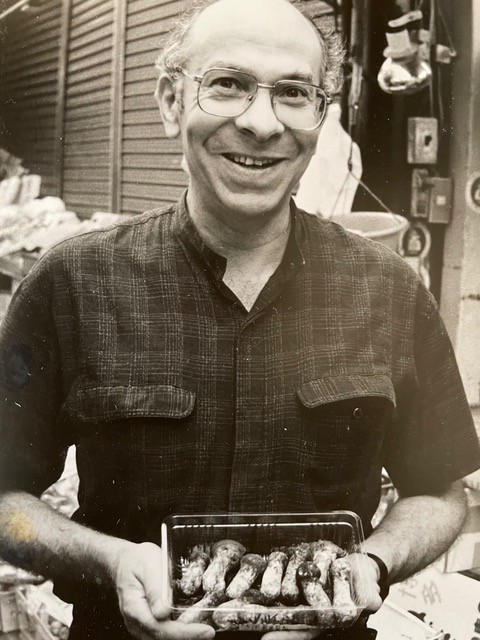

This is from a cooking column I commissioned from Kim for the Mainichi Daily News, shortly after he had left Kodansha in 1989. The topic of this particular offering: Japanese New Year soups. Kim said that this was the first time anyone had ever asked him to write. Really?! The portrait with matsutake was to be used with the column and we shot it in his local Tokyo neighborhood not long before he left for Gumma. I have been enjoying a good giggle as I revisit those cooking columns - and it is not without regret that we never did get Kim his own cookbook. Nevertheless, big thanks to Nancy and Lynne for this unexpected opportunity to ponder his confident quirkiness as a writer, not to mention his insights on soup and on Jewish grandmothers.

By the time I had left Japan 12 years after his first column it seems writing—under his own name as well as many pseudonyms (K. S. Rupert, Gil Isreal, H. M. Gusebaum…)—had become his mainstay along with the editorship of the Ikebana International magazine, passed on a year before I left, and which also became a platform for much of his writing on Japanese culture.

As much as I was informed and inspired by Kim’s writing on craft and culture, what I miss most are the odd-ball musings and odes he would almost always include in an email. Like this one teasing the tea ceremony tragic* in me:

Oribe he had an epiphany.

Said, "I'll copy the stuff made by Tiffany

And hide the bad bargain

With lotsa tea wabi jargon

Then I'll rake in much gelt in a jiffany."

[*tragic (Australian): "devotee; enthusiast”]

Did anyone else receive a copy of his “Memangerie” in which he channels Lewis Carrol in verses like:

Jimble with abandon, jounce your fundandle! Lo, the trilliloop, how it brinks, how it dandies.

Judging from his children’s book Tengu and the Thunderstaff (1966), Kim already had a head full of cheeky nonsense waiting for a platform from his earliest times in Japan. The name of the Tengu in his story is Ringoropyonpyontobijet

There’s that grandmother and her food again.

In the midst of all the challenges involved in maintaining his house in Shimonita: cleaning, washing, growing flowers, herbs, veggies, looking after pets and an automobile, and cooking with a woodfire stove (!) I marvelled at how he had any time or energy to write at all, least of all jimbly little dandies. In the summer heat it must have been a real trilliloop, as he once observed:

and I ought

to be working work;

but the mental is naught,

and the words is caught

in an oft fergot

blot

cause it's real hot

Money was short and things were often hard. I used to worry how he coped. But now that I find myself living in a hinterland not dissimilar to Shimonita, I can appreciate how much country living actually brought him joy and kept him connected to what was most important. Here’s my proof:

Dear Isa,

This year all the flowering trees made flowers at the same time. It was very beautiful, with white and pink and all kinds of red flowers and yellow too all together making color music.

And in my garden, the tiny yellow roses are just about to bloom.

And some flowers you can eat and some are good for making drinks. I am trying to make dandelion wine now.

And yesterday it was very hot with a hot wind. All the tiny dry flowers from the cedar trees were blown by the wind and fell like dry rain. And they go crunch when you walk on them.

(from a letter to my daughter aged 3)

Kim’s life had been full - a flavoursome, hearty hotpot, compared to my own clear broth. He would have made a great grandmother. But luckily for us all he left so much more than recipes for soup.

+++++++++++

Margaret Price worked at the Mainichi Daily News from 1982-1993 and then at NHK until departing Japan in 2003. She authored Traditional Japanese Inns and Country Getaways from Kodansha International among others. She remains a tea ceremony tragic now residing in Queensland Australia.

* * *

2021年8月3日、写真家三浦健司さまからいただいた思い出

(English translation follows)

Kimさんは、僕のことを「ミュウラク〜ン」と呼び、僕は「きむさん」と呼んで、少し曖昧なコミュニケーションをしながら仕事とうい旅を40年続け、2021年5月、その旅に終止符が打たれた。初めて心からKimって叫んだ。

Kimさんとの出会、それは講談社インターナショナル時代に始まる。すぐにいいコンビなった。その頃の僕は、北海道・道東出身で日本文化をほとんど識らない、まるでテキサスの片田舎から出てきた、都会に馴染めない青年だった。

理由は簡単。どでかいFordやNew Holland のトラクター、牛、馬、麦畑、おとぎ話をするフクロウなど、それまであったほとんどのものが無い。極めつけは空が青くなく星に色がなく、空気と水もとてもヘンな匂いと味がしたからだ。そして僕と関係のない人が、とんでもなくたくさんいた。ウチの村では、おおかた誰が誰だか見当がつくし、知らなくても見当はつけられる。

Kimさんは、そんな僕が、屋根が瓦で感動し、と同時に煙突がないと嘆き、水田に目を丸くし、そば屋が自転車で蕎麦をうずたかく積み上げて運ぶ姿に首を180度回すことを涙を流し笑い、面白がり、ケツを叩かれた。また、漆が木の樹脂だとか、紙でできた服があるとか、0.1㎜の線が描ける筆があるとか、あげくは、汚いぼろぼろの野良着が世界で人気なのだ…etcと。僕には、おおかたウソに思えたので必死に勉強しあれこれ調べ、次第に日本文化に興味を覚え、とくに工芸や食にのめりこんだ。実はKimさんの話しは、いつも本物ともっともらしいジョーク混じりの話しが多く、何が本当か理解し難くかった。だから僕は、なんでも必要以上に調べる必要があった。知識って、こーして深まるんだ。知らなかった。

僕が知ってるKimさんが暮らした大泉学園、花小金井、下仁田、どの家もどこかヘンで怪しく、時たまセクシーなものが飾ってあり、いつも子供には持てない程のヘビーなチョコレートケーキを食べさせてくれた。私の娘もよく連れて遊びに行ったが、良い意味での悪影響をたくさん与えてくれた。ある時、下仁田に家族で行き帰る時、Kimさんとトシオさんが築100年の古民家から、柔らかな陽の光りの中、手を振ってくれた光景が、今でも鮮明に目に浮かぶ。この光景は、僕が冥途の土産に持っていく唯一無二の大切な風景なのだ。

初めてジョークという習慣を魅せてくれたのもKimさんだった。でもKimさんのジョークは、初対面の人にも、長く仕事している人にも通用しなくてトラブった。でも傍目には最高のショーで、心の中で爆笑した。そんなとんでもないジョークを言っては、僕に振り向き舌を出してウインクしていた。「おいおい、それはマズイだろう」と言いたかったが、あまりにも楽しくて、お馬鹿なカメラマンとして共演した。今では、これと似たことを僕もやりだしてしてしまい、同じ墓穴を掘っている。コンビとは、そうゆうものだろう。

Kimさんは僕に、いろんな経験とチャンスをくれた。最初のロケは、妖艶な離婚調停中の陶芸家の作品と環境を撮る仕事。Kimは一日も来ないし指示もなかった。が、来たからいいものでもない。有松絞りの本では、著者の奥さんに箸の使い方が上手を言われ、激高。どうもKimさんは日本人になる瞬間があるみたいだ。撮影に関しては一切口出しなし。なんで?と訊いたら「職業名の後ろにerが付く人は、誰からも指示無しに仕事するものだ」と返事が返ってた。ウソだろ〜よ、僕はまだ新米のカメラマン。ションボリしたら、「神秘的な写真を」と。えっ!有松絞りを神秘的に?いくらなんでも乱暴だし、テキトー過ぎるだろう。

でも痛く納得し有松絞りは神秘的な写真と共に、美しい本になり本作りの虜にになった。以後、日本人編集者にもこの調子で仕事したら、たいへん怒られ幾つか仕事をなくした。僕はKimさんのやり方が好きだ。コンビとは、そうゆうものだろう。

海外ロケも最高だった。ある時サンフランシスコ行きのTicketをポンと渡された。Kimさんは先に行ってるから後から来るようにとの指示??????。僕は、英語圏に行くという不安も焦りもなく機材だけもって、のんきにSFOに。機中で白いカードが渡され、諸々の記入欄があったが、よくわからないから、所持金以外すべて空欄で入国審査に。そもそも英語を話せないから入国審査は、満面の笑顔で対応。そうしていたらKimが入国審査の通路を逆走して審査官に、何かわーわー言ってくれ3ヶ月の滞在許可が出た。アメリカはいい国だ、最高だぜ。

撮影は、朝鮮家具。Kimさんは、いつものように撮影に立ち会うこともなく、たぶん旧友を温めていたに違いない。僕はベイエリアの倉庫で2週間放置され撮影三昧。ランチ時間になるとfood truckがきて人種が分類できない巨漢の荷役の労働者と公園で毎日食事。当時僕は28歳の線の細い色白の美形男子(自画自賛)。今考えたら、これは危ないような気がするが、でも、休日はKimとゲイパレード見て、ベイエリアをドライブしてオイスターバーで食事。そしてコンサートに行った。サンフランシスコ最高。僕にピッタリ。コンビって、こーじゃなきゃ。

そしてインター時代にいくつもの本を作り、たくさんの人と出会いと多くのチャンスをもらった。だからいつも最高の集中力を発揮して撮影した。今でもおつき合いのある著者がたくさんいて、僕に多くのインスピレーションをくれる。

ANA のWINGSPANでは、もう数えられない数の取材を20年に渡り共にした。最初の頃は、Kimさんが企画を立ていたが、すぐに頻繁に、企画はないかと長電話がかかるようになり、僕が企画を立てるようになった。企画からプレゼン資料の作成、取材先の選定や取材許可、AirTicketの手配、レンタカー、宿の手配まで全て引き受け、Kimさんを連れて取材のワラジを履いた。取材先では「ミュウラク〜ンも何か質問ないの」とインタビューに参加するように求められた。何かヘンと思いつつ積極的に質問し、それに沿い撮影もした。これが日本の雑誌や本の制作で、ライティングもできるカメラマンとして役に立つことになった。Kimさんのいい加減は、僕のラッキーなのだ。コンビって、こーやって成長するんだ。

それにしても、この40年いっぱい仕事、一緒にしたね。どの仕事を思い出しても、おかしくて腹がよじれそうだ。全部珍道中、まさにお笑いコンビ。

僕はこの手紙を、病院のベッドの上で書いている。道は二つKimが呼べば、そう待たせることなく、また、面白い旅ができる。これもいい。もし、しばらくいいよ〜というのであれば待つけどね。まっ、任せるよ。どっちを選択しても恨まないから心配しないで。

さっ、Kimさん答えを聞かせてよ。ほら早く〜

そんなヘビーなチョコレートケーキを、食べている場合じゃないから。

Kim Kim Kimてば、

08/03/2021 三浦健司 (Kenji Miura)

Received August 3, 2021 from Kenji Miura, professional photographer

Kim Schuefftan, nineteen years my senior, called me “Miura-kun,” and I called him “Kim-san,” and we were colleagues for forty years, both of us communicating in a language of which our mastery was—you might say dodgy—until our journey together came to an end in May 2021. For the first time, I screamed “Kim!” from the bottom of my heart.

My encounter with Kim goes back to the 1980s when Kim was editor at Kodansha International (KI), where we soon found we made a good konbi team. At that time, I was a young photographer fresh from the Hokkaido’s Tokachi region. As unfamiliar with “Japanese culture” as a rancher from the Texas prairie, I was struggling to get used to the big city of Tokyo.

You couldn’t blame me. Nothing that I knew back at home—mammoth Ford and New Holland tractors, cattle, horses, wheat fields, owls like out of fairytales—existed in Tokyo. Worst of all, the sky wasn’t blue and the stars were wan. The air and water smelled and tasted strange. And there were ridiculous numbers of people around me I didn’t know. Back in Tokachi, I knew—or had some inkling about—almost anyone I would encounter.

The naive amazement that made a young frontier fellow stop to gaze at everything urban was immensely entertaining to Kim—how all the houses had tile roofs; that there were no chimneys; that the rice fields were filled with water; how I would jerk around 180 degrees to watch a delivery boy on a bicycle balancing a high stack of soba trays—he would laugh until tears ran down his cheeks and tell me, “now let’s get going!” And I learned all sorts of things from him: urushi lacquer is made from the sap of a tree; people actually make clothing out of paper; there were brushes that could paint a line as fine as 0.1 mm; and, most astonishing of all, worn and tattered workmen’s coats (boro) are collector’s items all over the world, and so much more... Still, I was never sure where Kim’s reliable knowledge ended and his tall tales began, so I had to really scramble to keep up with him. But in the process my own interest in Japanese culture grew, and I fell hard especially for crafts and food. Kim’s talk about a topic was invariably riddled with nonsense and joking around, and it was sometimes hard to be sure what was true. My strategy was to study up as thoroughly as possible so I could sort the wheat from the chaff. That’s how we get smart, right? I hadn’t realized that before.

The houses Kim where lived longest—the places at Ōizumi Gakuen, at Hanakoganei, and Shimonita—were all quirky and strange, sometimes with odd erotic items hanging here and there. He often served heavy chocolate cake, far too rich for children. Now and then took my daughter when I visited him and from Kim she got an “education” she certainly would not have received elsewhere. The scene after one such visit, of Kim and Toshio waving to us, haloed by the soft sunshine over the 100-year-old minka farmhouse where they lived for 30 years, is indelibly etched on my memory. That is one of those unparalleled and precious scenes I will take with me to my grave.

Kim was the one who introduced me to the culture of the joke. Kim’s jokes often befuddled not just people encountering him for the first time but those who had worked with him for a long time. You could see what great performances they were, and inside I rollicked with laughter. After making some preposterous joke like that, he would look over his shoulder and wink at me. My first impulse would be to scold him for his shenanigans, but it was, after all, so much fun; so I played along as the “dumb photographer.” Nowadays I find myself pulling the same shenanigans, so I guess I’m digging the same grave as he. Maybe that’s what happens in a good konbi.

I had a huge variety of experiences and opportunities thanks to Kim. Our first job together was to photograph the works and environment of a potter who was in the throes of a fascinating divorce process. Kim was absent for the first day and gave me no instructions. But he wasn’t much help even after he arrived. Sometimes his pet peeves got in the way. When we were doing the Shibori [1] book he blew his stack after the wife of one of the authors told him he was good with chopsticks. By then he had been in Japan for nearly two decades. I guess there were some things about not being Japanese that he didn’t think he needed to be reminded of constantly.

He never interfered with the photography. When I asked him why he never interjected, he replied that he believed “anyone whose profession ends in ‘-er’ could do their work without instructions from anyone else. “How can that be!” I protested, then being so new to the job. Then, to my forlorn look, he said: “capture the mystique [shimpiteki ni tore].” What! What’s the “mystique” of tie-dyed textiles! I thought he was being a bit rough on me. How random was that!?

Still, I came to keenly understand, and after capturing the mystique of Arimatsu shibori, a beautiful book was produced, and I became captivated by the processes of making books. The mode of close collaboration between Kim and me seemed to work well for these projects introducing Japanese culture for overseas readers. But it didn’t work with Japanese editors, as I soon learned after I got scolded and sometimes got fired. I loved the give-and-take and repartee with Kim. That’s how it is when you are a good konbi.

Our overseas trips were also great. One time I was handed a ticket to San Francisco. Kim had gone ahead, I was told, so . . . What? How was I to catch up with him there? But somehow I felt no uncertainty or worry about heading off to a place where only English is spoken, and packed my equipment. Turning up at SFO without a care, I was faced on the flight with a white card that I was apparently supposed to fill out. I didn’t really understand what that was for, so I left it all blank except for the part about how much cash I was carrying, and handed it over to the immigration officer. Since I couldn’t speak a word of English, I just kept smiling cheerfully, until suddenly there was Kim, going the wrong way in the line and jabbering at the officer about something, but then I had a three-month visa. I was impressed. The United States was a good country—it was a great country!

I was to photograph Korean furniture. Again, Kim did not turn up for the photographing—no doubt he was off somewhere catching up with his old friends in the Bay Area. I was left to my own devices in a Bay Area warehouse, and I spent that time just taking pictures of whatever I liked.2 At lunchtime, a food truck would come to the nearby park and there I’d be—a skinny, pretty-faced boy (if I do say so) of 28 eating my lunch alongside massive dockworkers of every imaginable ethnicity. That was back in the early 1980s. Thinking back, it might have been risky company. On my day off, Kim took me to see a gay parade and we drove around the Bay Area and ate at an oyster bar. We went to a classical music concert. San Francisco had everything! It suited me perfectly. This was what a good konbi should be.

While Kim was still at KI, we did several books together. I met a huge number of people and had many chances to do interesting work. So I was always really fired up and worked at my peak. Even now I continue to work with some of the authors I got to know then and gain great inspiration from them.

Over the twenty years of work with ANA’s Wingspan in-flight magazine we went on countless trips to do stories. Kim planned some of the early trips, but it wasn’t long before he started to call me, asking if I didn’t have an idea for a project. After a long phone call, it usually fell to me to work out a plan, come up with the presentation, choose the site for the interview, obtain permission for the interview, buy the airplane or train tickets, arrange for the rental car, and reserve the lodgings. So I became the general factotum for these trips. After we got there, Kim would want me to be in on the interview, calling me in to ask questions as well. Even as it seemed a bit odd for the photographer to be part of the interviewing, I got actively involved and took photographs to go along with what I was interested in. That experience was valuable in learning to become—in the production of magazine stories and books—a photographer who could not just take the photos but also write the stories. So Kim’s halfhearted efforts at preparation and planning ended up being my lucky chance. I guess any good konbi evolves in whatever way works best.

Well, Kim, we worked together for forty years. When I recall just about any of the jobs we did, I can’t help laughing out loud. Our trips were always full of incidents and accidents—and lots of laughter. We made quite a comedy duo.

I’m writing this letter from a hospital bed. The road forks here. If Kim calls, we might end up on another jolly journey. That, too, would be good. But Kim, maybe I can get you to wait a while longer. Whatever; it’s up to you. I won’t hold it against you, whatever you decide.

Now just get on with it and give me your answer, Kim—don’t keep me waiting! This is no time to be eating heavy chocolate cake.

Kim! Kim! Kim!

Kenji Miura

https://www.kenjimiura.net/

[1] Shibori: The Inventive Art of Japanese Shaped Resist Dyeing; KI 1983.

2 Korean Furniture: Elegance and Tradition; KI, 1985.

(translation by Lynne E. Riggs with Margaret Price)

Received from Yokoyama Yuko, www.handmadejapan.com, September 18, 2021. (English translation follows.)

キムの思い出

日本の伝統工芸の国内外へのPRの仕事をしていた頃、キムにはよく翻訳をお願いしました。その中で最も大きなプロジェクトは、出版社のダイヤモンド社創立60周年記念事業として伝統工芸産業大全のような出版物を英語、日本語、ビデオで各8巻製作するというものでした。自動車のトヨタがスポンサーにつき、数百セットがアメリカ各地の中学校に寄贈されたと聞いています。

その意欲的な出版物は、陶磁器、漆器、木工・竹工品、染織、鉄器、銅器、和紙など、概要を外国の人々に網羅的に紹介するという内容で、キムと私は本文はむろんのこと、膨大な量の写真の細かいキャプションを翻訳したことが記憶に残っています。連日、徹夜のような作業でした。もちろん、ネットで情報やふさわしい単語を調べられる時代でもなく、キムの広範な知識とカンの良さがあったればこそ、期限内で完成できたと思っています。当時、キム以外にこの分野で質の良い翻訳をできる人はいなかったと思います。

ある時、群馬のお家にお誘いを受け、山中の民家を訪問しました。雲を下に見る絶景に息を飲みました。家の中は、様々な一見ボロのような古美術品で足の踏み場もなかったことでした。けれども、翻訳の仕事も減り、関次さんと二人して、こんにゃく工場の夜勤仕事をしていると聞き、胸を痛めました。

頑固な上に、頭の回転が速すぎるのか、相手の反応を先回りしてしまったり、クライアントと気まずくなったことも耳にしていましたが、幸い、私とは一度も喧嘩することなく仕事ができました。愛すべき人柄、ユニークなキャラクターが偲ばれます。 ご冥福をお祈りいたします。

横山祐子

http://www.handmadejapan.com

Remembering Kim

Back when I was involved in promoting Japan’s traditional crafts in Japan and overseas, I often asked Kim to do translations. Among the biggest projects we collaborated on was a project commemorating the 60th anniversary of the publisher Diamondo Sha. It was an 8-volume video set in both English and Japanese covering the entire traditional crafts industry. The automobile manufacturer Toyota came on as sponsor and I heard that several hundred sets of the videos were donated to junior high schools around the United States.

For this ambitious publication, which was intended to introduce general information on the entire spectrum of crafts—ceramics, lacquerware, woodworking, bamboo craft, weaving and dyeing, iron work, copperware, washi paper, and so on—Kim and I did the translation of all the main texts and of course for all the detailed captions for the massive number of photographs included. I remember the many consecutive all-nighters we pulled to get it done. Of course, that was before the days of the Internet—when one can look up whatever term and expression one needs on the Web—and it was only thanks to Kim’s broad knowledge and intuitive sense for language that we were able to complete the project on time. At the time, I believe there were few translators conversant with the traditional crafts who could have helped us out.

Once I visited Kim in his minka deep in the mountains of Gunma. The view from the house, overlooking clouds in the valley below, was breathtaking. Inside, the house was filled with antiques, what looked at first glance like rags, and countless stuff, leaving barely room to walk. I was stunned when I later heard that when the translation and other work fell off, Kim and Sekiji-san were doing graveyard shift at a local konnyaku factory.

Kim was stubborn, very smart, and sometimes almost too quick to grasp a situation. I have heard that there were cases when those qualities got him into trouble with clients, but fortunately I never once quarreled with Kim in all the work that we did together. I will miss his lovable personality and his one-of-a-kind character.

Kim, please rest in peace.

Yokoyama Yuko

www.handmadejapan.com

Received from Kunikatsu Seto, Wajima lacquer craftsman, Septebmer 23, 2021. (English translation follows.)

ある先人の言った言葉に『自分の死をもって人に無常観を教え、自分の死をもって生きているありがたさを教える』とあります。

キムシュフタンは、世界の美術工芸を日本に紹介し日本の美術工芸を世界に発信し続けました。彼が仕事を通して知り合ったクロードレビストロースやマイケルティ ルソントーマスなどを輪島の地に誘い彼らにこの地を見せてくれました。

私が特に思い出されるのは、彼がバーナードリーチと浜田庄司両人を1973年に輪島へ連れて来てくれた事です。二人は時間のある限り物の見方、考え方の根本を熱く語り、この町で漆の仕事に携わる人達に大きな衝撃を与えたのです。

その後のバブル崩壊や工芸を取り巻く環境が一変しても、その時代の変化に対応できる作り手達がキムの努力によって誕生している事がそれを証明しています。

私にとっても工芸の師であり心の友であったキムシュフタンに捧げる言葉は『ありがとう』であり、今は安らかに彼の冥福を祈りたい。

石川県輪島市河井町

瀬戸 國勝

A wise man once said: “In dying we teach others of the transience of life; with our death, we teach them of the blessings of life.”

Kim Schuefftan devoted his life to introducing world arts and crafts to Japan and to introducing Japan’s arts and crafts to the world. Through his work, we were able to have people like anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss and conductor and composer Michael Tilson Thomas visit Wajima and show them our world.

For me what was most memorable was the time in 1973 when Kim brought Bernard Leach and Hamada Shoji to Wajima. In the limited time they had, they spoke passionately about how they saw things and the basis of their thinking and their visit had a big impact on people engaged in lacquerware making in this town.

That Wajima lacquerware makers have been able to cope with the changing times, even with the bursting of the bubble economy and the transformation of the environment surrounding crafts, testifies to what was born through the efforts that Kim made at that time. Kim was my mentor (kōgei no shi) and fellow spirit in crafts. Kim, I honor and thank you! I pray you will rest in peace.

Seto Kunikatsu

Kawai-machi, Wajima, Ishikawa prefecture

http://www.seto-kunikatsu.com/

Received from former Kodansha International editor Akamatsu Tsuko, October 1, 2021 [English translation to be added]

キムさんの思い出

Kim Schuefftan、(以下キムさんと呼ばせてもらいます)は私にとって初めて関わる「ガイジン」でした。

講談社インターナショナルに入り、与えられたデスクはキムさんのすぐ脇。キムさんがかける電話の声まで細かく聞こえる席でした。当時私は23歳、特別に国際的な家庭に育ったわけでもなく、ごくごく普通に暮らしてきていて、キムさんの存在はカルチャーショックそのものでした。仕事をするにあたって、職場の先輩(とくに女性が強く、生き生きと働いている職場でした)から「キムには大人しく従っていてはダメよ。強く主張しないと舐められちゃうから」となんとも心強いアドバイスをもらい、さてどう付き合っていくものやら。

キムさんはみごとな日本語を話し、美術や芸術に関しては本当に深く理解している人でしたが、かなり「意地悪」な人だったのです。何か商品購入のクレームで電話で話しているようで(みんな聴こえちゃう席の近さ!)ペラペラと英語でまくし立てて、散々話しを進めた挙句に(たぶん先方は苦心惨憺、英語で対応していたと思う)とつぜん日本語に変わり「これについてどういう対応をしてくれるんですか?」と相手をケムに巻くことなど、日常茶飯事でした。一緒に一冊の本を担当すると、新入りの編集者を教え導くというより、ゴーイングマイウェイ。初めはビクビク従っていましたが、これではいけない!と疑問点は正し、納得いかないことにはNOと言い、新入りとしては精一杯の背伸びをしているうちに、キムさんの態度も変わっていき「内山さん(仕事は旧姓の内山でとおしていました)は僕に辛く当たる」と別の編集者に愚痴を言っていたこともあったそうです。

喧嘩もしたし、時間のルーズさに腹を立ててしばらく口を聞かないこともありましたが、キムさんの仲直りの方策は独特でした。犬も猫も鳥も、動物大好きのキムさんは、同じように生き物好きの私の機嫌を直させるために、とっておきの動物話しをするのです。「僕のうちの犬がねぇ」と始まり、話が終わる頃にはすっかりキムさんペースに乗せられ、仲直りしていました。アヒルを飼っていたこともあって、名前が「どうして」ちゃん。目が合うとどうして?どうして?と聞かれるから名付けたそうでした。動物に対して本当に優しい、愛情豊かな人でした。夜中に私の愛猫が急に具合が悪くなり、もうどうにもならず、思いあまってキムさんに電話をして、夜中でも駆けつけてくれる獣医さんを教えてもらったこともありました。(「良い獣医さんだよ、だけど高いよ」とキムさんに言われ、本当に泣きたくなるような医療費でしたが)おかげで猫の命は助かり、キムさんは命の恩人でもありました。

漆のこと、職人さんのこと、日本の地方の伝統工芸のこと、などなど、キムさんに教えてもらったことはたくさんあります。講談社インターナショナルという特殊な職場で長い期間仕事する機会をもらい、キムさんをはじめ何人もの優れた外人編集者と密に働くことで、山ほど学ばせてもらいました。日本の文化についても改めて素晴らしさを再認識することができ、思い残すことのないほど充実した編集者生活でした。

キムさん、本当にありがとう。どうぞ安らかにお眠りくださいませ。

キムさんのご冥福を心よりお祈りいたします。合掌。

赤松(旧姓 内山)通子 いすみ市大原

Received from Takagi Shinji, architect, December 20, 2021, via Yokoyama Yuko

キムさんの思い出

私が1975年に故郷の輪島にUターンで帰って来て設計事務所を開設した頃は輪島の朝市は訪れる観光客もほとんど少なくて昔ながらの生活朝市で賑わっていた。昔からの友人に新しく東京から来た関次俊雄さんも加わり「モノ」や「町」について飲みながら語りあった。関次さんの友人のキムさんは突然ふらりと輪島に現れた、そして愛嬌のある真面目な顔で話しかけてきた。はじめは何をしている人か分からなかったが少しづつわかってきた。

そのキムさんは電話を掛けてくるときはいつも独特の愉快な一方的な話し方であったが今から思うとどんな挨拶よりもその時のキムさんの気分がハッピーであることが分かるのであった。キムさん、関次さんと輪島の友人5人で仲間が出来た。そして古い土蔵を改装してギャラリー「座」がオープンしたのである。

最初の展示物はほとんどがキムさんの「刺し子」など日本の生活用具のコレクションだった。何年かたった頃、キムさんは能登のどこか小さい村で住みたいと言ってきた。能登半島の山間部の坂田という小さな村の農家と半島の東側のこれも寒村の岩車というところの空き家を一緒に行って調べてみたことがあった。どちらも農家の使われなくなった納屋のような建物であったがそこはまさしくキムワールドであったのではないかと回想する。

高木信治

高木信治建築研究所

輪島、石川県

Comments:

While recently once again browsing the history of SWET, I came across Kim’s name. My name was there as well because we both were part of the group that formed SWET in 1980. Curious about what Kim was up to these days, I Googled his name and was surprised to learn he had passed away last year.

I met Kim in the 1970s when I was chief editor of the International Division at the University of Tokyo Press and he was an editor at Kodansha International. At the time, the four main publishing companies that focused on bringing out English books about Japan, Tuttle, John Weatherhill, Tokyo Press and Kodansha, competed for the scarce supply of competent English-language copyeditors and proofreaders in Japan. Eventually, SWET was formed to help rectify this situation. Before this, I had often consulted with Kim and other foreign editors at Kodansha, as well as with Suzy Trumbull and Becky Davis who were editors at Weatherhill, about finding suitable people.

I remember Kim as an extremely precise and dedicated editor who often was at odds with the managing director of Kodansha International, the very affable, but stern Saburo Nobuki. When Nobuki retired and set up his own international publishing venture, International Publishing Institute, Kim joined him.

I have very fond memories of Kim so it is sad to see that he has departed for greener pastures. I wish him well, wherever he is.

By Amadio Arboleda on February 6, 2022

Thank you, Marty for your quick and juicy inside look at the workings of a fairly complex and very quixotic man. His death took us by surprise and leaves many questions about his fascinating life and accomplishments in Japan. You answered many of them. Thank you. He was an impossible and wonderful, sweet and cantankerous man and I am not alone in thinking that life will not be the same without him!!!

By Amy Katoh on June 6, 2021

Add your comment:

If you are a SWET member, log in to post a comment immediately. Comments are moderated for non-members.