July 23, 2010

The Hadashi no Gen Project

by Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason’s experience as a translator began in 1977 with the manga Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen), as part of a volunteer project that continued for 30 years. Project Gen inadvertently became the world’s first publisher of manga in translation when it issued Barefoot Gen Volume One in 1978. With the tenth and final English volume completed in 2009, the Gen series bears witness to the evolution of the translation of manga over three decades. Gleason described that evolution at a session of the 21st International Japanese English Translation Conference (IJET-21) in April 2010, and agreed to write about it in detail for SWET members as set down in this article.

The first document I ever translated was a manga. In the summer of 1977, I was living in the suburbs of Tokyo, studying traditional Japanese music and teaching English for a living. One day I met a group of hippies who were living in a communal household near my apartment. They urged me to drop by and help out on a mysterious translation project they were engaged in. When I showed up a few days later, I was led upstairs to a room full of young people, both Japanese and American, seated around a long, low table. They were feverishly filling text balloons with English lettering on pages of a manga I had never seen before.

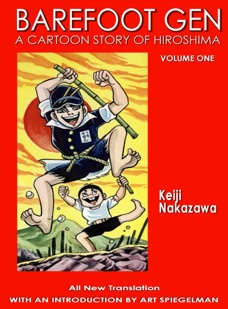

The images seemed to consist of the most graphic and awful scenes imaginable of some sort of holocaust. “Here, read this,” someone said, and shoved a tankobon into my hands. I started reading and was immediately hooked. The manga was Hadashi no Gen (はだしのゲン), by Nakazawa Keiji (b. 1939), the horrific, yet humanistic, graphic novel about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen through the eyes of a six-year-old boy who lived to tell the tale. The people around the table were volunteers of a group called Project Gen. They were busy preparing a pamphlet introducing the climactic sequence of the first volume of Gen: the dropping of the bomb and its immediate aftermath. I was quickly “volunteered” as a native-English proofreader, and so began an involvement that continues to this day.

It was the work’s unblinking depiction of the reality of nuclear war that compelled me, as well as the other volunteers, to help translate Gen into English. But volunteering for the project also proved prescient as a career move. I hated teaching English and was looking for some other way to pay the rent, but I had never considered translating. It was not until several years later that I hung out my shingle as a full-time freelance translator (and most of my early professional work was on patents, not manga). But Gen provided the first real opportunity to try my hand at J-E translation, and I found the process much more satisfying than I had imagined.

It was the work’s unblinking depiction of the reality of nuclear war that compelled me, as well as the other volunteers, to help translate Gen into English. But volunteering for the project also proved prescient as a career move. I hated teaching English and was looking for some other way to pay the rent, but I had never considered translating. It was not until several years later that I hung out my shingle as a full-time freelance translator (and most of my early professional work was on patents, not manga). But Gen provided the first real opportunity to try my hand at J-E translation, and I found the process much more satisfying than I had imagined.

Years later, after I had moved back to the United States and had established myself as a technical translator, I did start translating manga for money. The work that came my way, however, was mostly of the science fiction/fantasy, androids-from-Mars variety. Though great fun, these translations were just a job. Opportunities to translate manga with serious content like Gen were—and still are—few and far between. Nonetheless, subject matter aside, manga as a translation sub-genre has definitely come into its own.

Nowadays, of course, manga and anime are a global pop-culture phenomenon, and publishers of manga in translation occupy their own significant niche in the American comics industry. Until the late 1970s, however, the only examples of Japanese cartooning to gain mass exposure in the English world were animated works like Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu), which appeared on American television in the 1960s.

I had grown up in Japan, living in Tokyo for most of the period from 1956 to 1969. At some point we acquired a black-and-white TV, and I remember watching sumo matches, but I paid little attention to Japanese cartoons. For one thing, I lived in an English-speaking environment at home and at school, and didn’t understand Japanese that well. (On the other hand, my little brother, who spent the first five years of his life in Japan, was a big fan of TV superheroes like Ultraman, Ultra Seven, and Ogon Bat. Having attended the neighborhood yochien, he spoke Japanese more fluently than anyone else in our family.)

It was not until I returned to Japan in my early twenties that I began reading manga in earnest. I had enjoyed American comics when I was young, even amassing a sizable collection of the Classics Illustrated series (very handy for writing book reports without reading the actual book), and in college I had grown fond of underground comics like Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix, which didn’t just push the envelope when it came to graphic depictions of sex, violence, and drug use, but shattered it. Even so, neither Zap nor the popular manga I perused on trains or in coffee shops (my tastes ran to “young adult”-oriented weeklies like Big Comics or Manga Action) prepared me for my first encounter with Hadashi no Gen.

This brutally vivid recounting of the real-life holocaust that took place in 1945 was first serialized in the pages of Shukan Shonen Jump (Weekly Boys’ Jump), Japan’s best-selling manga weekly, which was ostensibly targeted at teenage boys. Even by the seen-it-all standards of Japan’s all-encompassing manga market, Gen stood out like a sore thumb. It was both widely read (Shonen Jump had a weekly circulation of over two million) and controversial—not so much for its depiction of the horrors of the bombing as for Nakazawa’s scathing critique of the Japanese militarists who started the war, and of the imperial system itself. Despite its popularity with readers, Jump abruptly cancelled the series after an 18-month run, and though accounts vary, many believe this was due to political pressure on the publisher.

This brutally vivid recounting of the real-life holocaust that took place in 1945 was first serialized in the pages of Shukan Shonen Jump (Weekly Boys’ Jump), Japan’s best-selling manga weekly, which was ostensibly targeted at teenage boys. Even by the seen-it-all standards of Japan’s all-encompassing manga market, Gen stood out like a sore thumb. It was both widely read (Shonen Jump had a weekly circulation of over two million) and controversial—not so much for its depiction of the horrors of the bombing as for Nakazawa’s scathing critique of the Japanese militarists who started the war, and of the imperial system itself. Despite its popularity with readers, Jump abruptly cancelled the series after an 18-month run, and though accounts vary, many believe this was due to political pressure on the publisher.

Precisely this subject matter, and Nakazawa’s pull-no-punches style of presenting it, were what made Gen attractive to the young people who gathered to translate it in the late 1970s. There was no commercial market for manga in translation yet; the surge of overseas interest in manga would come several years later. We didn’t know it at the time, but when we printed 1,000 copies of the first volume of Barefoot Gen in 1978 and shipped them in boxes to a sympathetic non-profit group in New York, Project Gen became the world’s first publisher and distributor of manga in translation.

Pioneering Production Techniques

Since we were unwitting pioneers in the field, we developed our translation and production techniques entirely by trial and error. Some of the issues we confronted were, of course, common to translations of any prose work. But the language was the least of our challenges. Author Nakazawa, himself a survivor of the atomic bombing who grew up in Hiroshima, had created a plain-spoken narrative based on his own experiences and those of his immediate acquaintances. Like his young protagonist, Nakaoka Gen, who is modeled after the author, Nakazawa lost most of his family in the fires that followed the bombing, and had struggled to survive in the harsh environment of postwar Hiroshima. Early on, however, he showed a flair for drawing, and when he grew up he moved to Tokyo to pursue a career as a professional cartoonist. Gen was the first serialized manga he produced that was based on his own experience as a hibakusha (survivor of the atomic bombing).

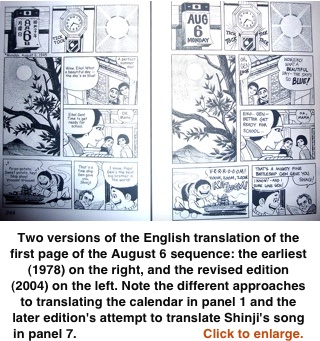

Nakazawa brought the characters in Gen to life with lively, realistic argot, incorporating the pun-riddled Hiroshima dialect of local kids, the street slang of low-echelon hoodlums, and the jingoistic rhetoric of wartime politicians. By the time I joined Project Gen, some good writers among the American volunteers had set a tone for the English dialogue that veered a bit toward the slangy. In Volume One, the atomic blast sends a concrete wall toppling onto Gen, knocking him out but saving his life. When Gen regains consciousness, his first words are: Na, nande konna hei ga (な なんでこんなヘイが). In Project Gen’s earliest translation this was rendered: “Wow! What’s with this wall?” We later changed this to: “W-why am I under this wall?”

Though we toned down the Americanisms in later editions, we tried to keep Nakazawa’s breezy idiomatic style intact, using plenty of “gotta’s” and “gonna’s.” Generally, the dialogue in Gen proved surprisingly easy to render into colloquial English. Much later, when I began translating playscripts, I found that dialogue translation came as second nature to me after all those years of work with manga.

The Hiroshima dialect of his characters, which Nakazawa had already diluted a bit for a nationwide readership, was less of an ordeal to translate than the songs, nonsense rhymes, dirty limericks and puns that pop up throughout the story. Like kids everywhere, Gen and his friends delight in singing their own parodies of everything from sappy love songs to patriotic war ballads. Translating these ditties inevitably forced us to make a choice between adhering faithfully to the original, which could produce rather clunky-sounding lyrics, or creating a looser version that might even rhyme in English and reflect the mood of the original, but sacrifice its Japanese flavor. In Volume Two, for example, Gen hitches a ride on a fishing boat and sings the following verse:

われは海の子 白波のさわぐいそべの松原に

Ware wa umi no ko shiranami no sawagu isobe no matsubara ni

This is how we rendered it in our first edition:

Oh, I’m from Matsubara where the waves break on the sand

To round out the song a bit, our translators took a bit of license and made it a couplet by adding:

I’ll spend my life a-sailing, I’ll sail the world so grand

However, after being informed by Japanese colleagues that matsubara was not a place name, but a generic term for a seaside pine grove, we revised this in a later edition to the somewhat more literal but less bouncy:

Oh, we’re children of the waves, born by the tide

In the piney woods down by the seaside

Another dilemma we faced was how profane to make Gen and his friends. In the original, they are pretty darn foul-mouthed, to a degree that might shock some American readers, considering that the original target audience for Gen was schoolboys. Kuso kurae, the Japanese equivalent of “eat shit,” appears frequently. After a bit of soul-searching—though admittedly not much—we decided early on to permit the occasional “shit” or “damn,” but nothing more vulgar. There are still occasional protests over the language in Gen from concerned parents of young readers in the United States.

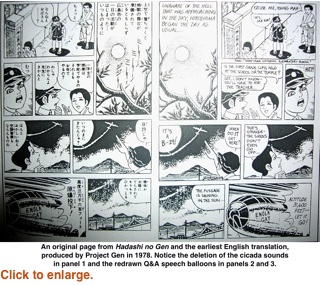

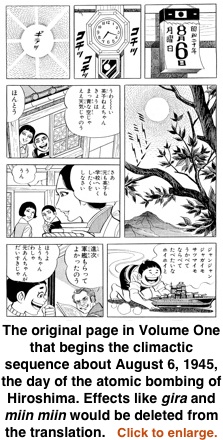

The biggest hurdles in translating manga text into English are surely the sound effects. The Japanese language lends itself well to onomatopoeia (giongo), and manga artists avail themselves of a vast and eloquent range of sounds—the zā zā of a downpour, the byū byū of a whistling wind—as well as a distinct class of mimetic (gitaigo) effects that do not represent sounds at all, but moods or feelings. Manga abound with such expressions as the niyari of a sinister leer, the kira! of a blazing summer sun, or the shiin of utter silence. While the relatively paltry palette of English onomatopoeia may serve in a pinch for translating actual sounds, the non-sound effects are pretty much a lost cause. Often, manga translators have no choice but to delete them completely. Even certain “real” sounds are problematic: the miin miin miin of summer cicadas, used frequently by Nakazawa to evoke the sultry August days in Hiroshima, got axed by the translators because we thought a disembodied BUZZ BUZZ BUZZ would only puzzle English readers.

More than any of the words, however, the pictures are what make manga translation a unique challenge, posing problems not encountered with text-only literature. To begin with, Japanese reads right to left; hence the panels on a given manga page follow a sequence from right to left, top to bottom. So do the speech balloons within a single panel: if there is a question-and-answer exchange between two characters, the question will appear on the right and the answer on the left. To compound the problem, the Japanese text in manga balloons is printed vertically, so the balloons themselves often have to be redrawn to fit the horizontal English text.

These design issues were not something that the first Project Gen volunteers gave any thought to  when they decided to translate Gen. New and unforeseen problems seemed to crop up daily. Without any manga translation precedent to follow, we had to improvise as we went along. And in those pre-computer days, everything had to be done by hand. We made photocopy enlargements of the original pages, cut out all the panels, rearranged them in left-to-right sequence, then scrutinized each panel for further trouble-shooting. Some pictures merely entailed whiting out the Japanese dialogue and lettering the English translation into the same space. Others required re-drawing the balloons, either to fit the English or to re-order a question-and-answer dialogue. In extreme cases we would have to “flop” the entire panel, making a photostat of it to produce a reverse image.

when they decided to translate Gen. New and unforeseen problems seemed to crop up daily. Without any manga translation precedent to follow, we had to improvise as we went along. And in those pre-computer days, everything had to be done by hand. We made photocopy enlargements of the original pages, cut out all the panels, rearranged them in left-to-right sequence, then scrutinized each panel for further trouble-shooting. Some pictures merely entailed whiting out the Japanese dialogue and lettering the English translation into the same space. Others required re-drawing the balloons, either to fit the English or to re-order a question-and-answer dialogue. In extreme cases we would have to “flop” the entire panel, making a photostat of it to produce a reverse image.

Eventually, flopping the entire manga would become the modus operandi of commercial publishers of manga in translation, since it obviated the need to do all that onerous cutting and pasting. However, indiscriminate flopping presented its own problems; reversing the original images would, for example, make all the characters left-handed. (Early readers of translated manga may have wondered if all Japanese were southpaws.) Indeed, the question of whether to flop or not to flop has been a perennial issue throughout the brief history of manga translation. When Project Gen started out in the late seventies, it took half a dozen volunteers about a year of weekend cut-paste-and-letter sessions to produce each volume. By the time we published Volume Four in the United States in 1994, manga translation was a viable commercial enterprise and certain production procedures had become standard. One of these was to flop the entire work from the outset. Though this met with some protest from the cartoonists, who did not like to see their work in mirror-image, the southpaw aspect did not really seem to bother English readers, and the auto-flopping made translated manga much quicker and cheaper to publish.

Back to Graphics Fidelity

|

|

In the meantime, Nakazawa had continued to serialize installments of Gen in various small periodicals, until the saga filled ten book-length volumes. The original Project Gen had entered a long hiatus after only four were translated. But in the early 2000s a new group of volunteers, also named Project Gen, was formed in Kanazawa to translate the entire series into Russian. When this was completed, they decided to translate the remaining six volumes into English, as well as re-translate the first four. The author put the Kanazawa group in touch with me, and I agreed to help them revise Volumes One through Four and to edit their translations of the remaining volumes. Advances in personal computer technology now meant that all the image flopping, balloon redrawing, and lettering work could be carried out on a computer, and the page images could be transmitted via the Internet. This speeded up the production process considerably.

Inevitably, computers also encouraged a tendency to attempt over-fine tuning of the images. The volunteers’ fixations with certain issues reflected an interesting cultural divide. The Americans tended to want all the left-handed action (punches thrown, guns brandished) to be converted to right-handed, and our Photoshop ace graciously complied, proving highly adept at changing left fists to right. Meanwhile, the Japanese members of the team were concerned that the collars of the characters’ kimono now overlapped in the “wrong” direction reserved for the deceased in funeral dress. All the collar-lines were diligently redrawn so as not to offend the sensibilities of Japanese readers of the English edition.

Once the reconstituted Project Gen got rolling in 2005, we were able to produce two new volumes a year, finishing the tenth and final English volume in 2009. (All ten volumes of Barefoot Gen can be ordered from the American publisher, Last Gasp.) To date, Gen has been translated, in whole or in part, into 22 languages worldwide. Some of these other language editions were completed well before the English; others were translated from the English volumes as they became available.

Because of its subject matter and the fact that it is a volunteer project, the Gen translation effort stands a bit removed from the manga translation industry in general, which has undergone a number of booms and busts in recent years. Currently, translated-manga sales in the United States are down, but then, so are manga sales in Japan. Blame the Internet, the reading habits of the youth of today, the global recession—no doubt all are factors.

Yet there is no disputing the fact that a manga fan base has taken root outside Japan. Over the years this readership has grown in numbers, sophistication, and familiarity with manga conventions, and its demands on translators and publishers have evolved in unforeseen ways. First and foremost is a concern with “authenticity,” by which is meant fidelity to the original manga. As we know, a truly “faithful” reproduction of the original is a practical impossibility in translation, at least in the realm of text. Graphics, however, are another matter, and publishers have found it expedient to accommodate the purist expectations of overseas manga readers when it comes to retaining the original artwork, because it means less time and money spent on altering the graphics.

The “flopping” issue thus has now come full circle, with American fans in particular demanding that their translated manga appear in the original right-to-left sequence. Impressively, these readers—dubbed “neo-otaku” by some—are quite willing to train themselves to read from right to left, counterintuitive though it would seem for them. They also like to see the original hand-drawn effects left intact on the page, since they regard the lettering as part of the original art. (Translations of the gitaigo and giongo are usually provided in footnotes beneath the panel.)

If the manga translation business survives its current woes, it may prove to be an early indicator of a new wrinkle in the globalization of popular culture, exemplified by young Western readers who are perfectly happy to read their translations of Japanese manga in the same order that Japanese readers do. Surely this is the first instance of Japanese reading habits catching on in the West, rather than the other way around. Perhaps through manga the world will finally learn that globalization can be a two-way street.

Originally published in the SWET Newsletter No. 125 (August 2010).

© 2010 Alan Gleason