November 6, 2021

Writing from Japan: English-Language Newspaper Columnists in the 1980s and 1990s—Mark Schreiber

As part of SWET’s 40th anniversary celebrations, we are chronicling the memories and experiences of some of the many columnists of that era. We have asked these writers to reflect on how they wrote and communicated back in the pre-digital days, a time when Japan boasted four English-language newspapers and plenty of magazines looking for English-language contributors. It was a golden age for Japan-based writers before the Internet and social media changed the way we live and work. This is the fourth installment in the series.

Recalling the Slow, Old days of Low-tech

By Mark Schreiber

When I was growing up, my father on occasion would begin a sentence, "When I was a boy, we didn't have..."

In 1977, when I was a 30-year-old man, Apple Computer Corp. was just one year old, operated by Steve Jobs and a small number of geeks. And things like PCs, home faxes, modems, cell phones and social networks were still just gleams in their inventors' eyes.

Nevertheless I did not particularly regard my life as being hobbled by a lack of technology. After all, cars had electric starters instead of cranks. That said, in 1977, I could never have imagined the changes that would soon take place.

Over the 12 years from 1983 to 1995 I went from electric typewriter to PC, from postal system to facsimile to modem, and from hand carrying or mailing floppy disks to emailing text and image files and on-line shopping.

My first significant encounter with the primary tool of the writing trade came in the summer of 1961, when I was between 8th and 9th grades. My father enrolled me in a six-week long touch typing course in Albuquerque Business College. I was the only male in the class, which was made up nearly entirely of Latinas fresh out of high school taking courses in stenography and typing, using Royal electric typewriters.

Before and after classes those gals teased me, unmercifully, but I persisted, and my familiarity with the QWERTY keyboard from a relatively young age was to prove beneficial. Through my high school and university years, I was able to hand in neatly typewritten essays and research papers that were appreciated by my instructors, if not for style or content then at least for legibility.

I graduated from high school in Fayetteville, North Carolina in May 1965, and three months later accompanied my military family to Okinawa, arriving just in time to enroll in the autumn semester of the University of Maryland, Far East Division.

The following year I applied for admission to International Christian University in Mitaka and was accepted as a transfer student. The school introduced me to a Japanese family in the city of Chofu on the Keio Line. The husband's father had formerly been a viscount, and they owned two houses: a Japanese-style home next to a brick house with stained glass windows and a real fireplace. I had a 6.5 tatami room to myself, with a sink, small kitchen and "frash toilet" (that's how it was spelled on the contract).

The family rented out their Western-style brick house to an American engineer employed on one of the nearby military bases. When he returned home from work after dark he would drive past my room in his enormous 1959 Cadillac, causing the house to rattle, and causing me to marvel how strange it was that an earthquake occurred almost every evening at the same time.

While at ICU I concurrently took courses in Chinese, which I'd picked up on Okinawa, and Japanese, along with a course in English literature and journalism taught by the late Holloway Brown, who also served as an editorial writer for The Japan Times.

After graduation from Washington University in St. Louis in 1969 I was admitted to Taiwan Normal University in Taipei for postgraduate studies in Chinese, and it was there that I encountered Peter Forgham, a brash young American entrepreneur who claimed to be the successor to Thailand's first "Thai Silk King." The original king, a former American intelligence officer named Jim Thompson, had mysteriously disappeared over Malaysia while aboard a light aircraft in March 1967. Impressed that I spoke both Japanese and Chinese, Forgham hired me to manage his Thai gift shop at the International Bazaar at Expo 70 in Osaka.

My first regular employment in Japan was at JALPAK, a JAL-affiliated travel agency, from 1972 to 1974. While there, I learned how to operate the telex, a bulky communications device that for many years served as a standby in the travel and airline industries. After a short hiatus in the Middle East and Europe, I returned to Japan and eventually found employment with Aiwa, a maker of portable radio-cassette players, microphones and other audio equipment in which Sony held a majority share.

Initially my in-house duties involved translation and copywriting. Aiwa put me to work starting with owners' manuals, brochures, sales manuals, press releases, an English newsletter and the president's English speeches.

One day in 1977, while dribbling perspiration in the sauna at Clark Hatch's gym in Azabu, I ran into the late Millard "Corky" Alexander, publisher of the popular free community tabloid, Tokyo Weekender. I told Corky I had some ideas for stories and he invited me to submit them. My first was about Japan's nascent antismoking movement, which was followed by an account of what it was like to fast for 10 days in a Buddhist temple.

In those days writers basically had three ways to submit drafts to Weekender editors. One, if in a big hurry, you could take the train to the publisher's office near the Tokyo Tower and hand the document over in person; two, you could mail it to them in an envelope; or three, you could dictate the text over the telephone to an editor, who would type it out, a line at a time. (I once called in an article from Kyoto to meet a deadline in Tokyo.)

As my freelance work picked up, I gave up my old portable Olympus electric typewriter for a Brother "Zorongo," the local rip-off of the IBM Selectric. The considerably cheaper Brother also featured a "golf ball" type element and built-in correction ribbon, with which you could use the backspace key to automatically overstrike errors—quicker and cleaner than dabbing the page with correction fluid. Armed with a better typewriter, my output—and range of topics—picked up considerably.

Then one day while eating lunch in a coffee shop in the basement of Aiwa's office building I picked up one of the free Japanese weekly magazines put out by the proprietor and read about the recent opening of Japan's first capsule hotel in Osaka. This was only a month after the term "rabbit hutches" to describe Japanese urban housing had come into vogue, and the timing for such a story was perfect.

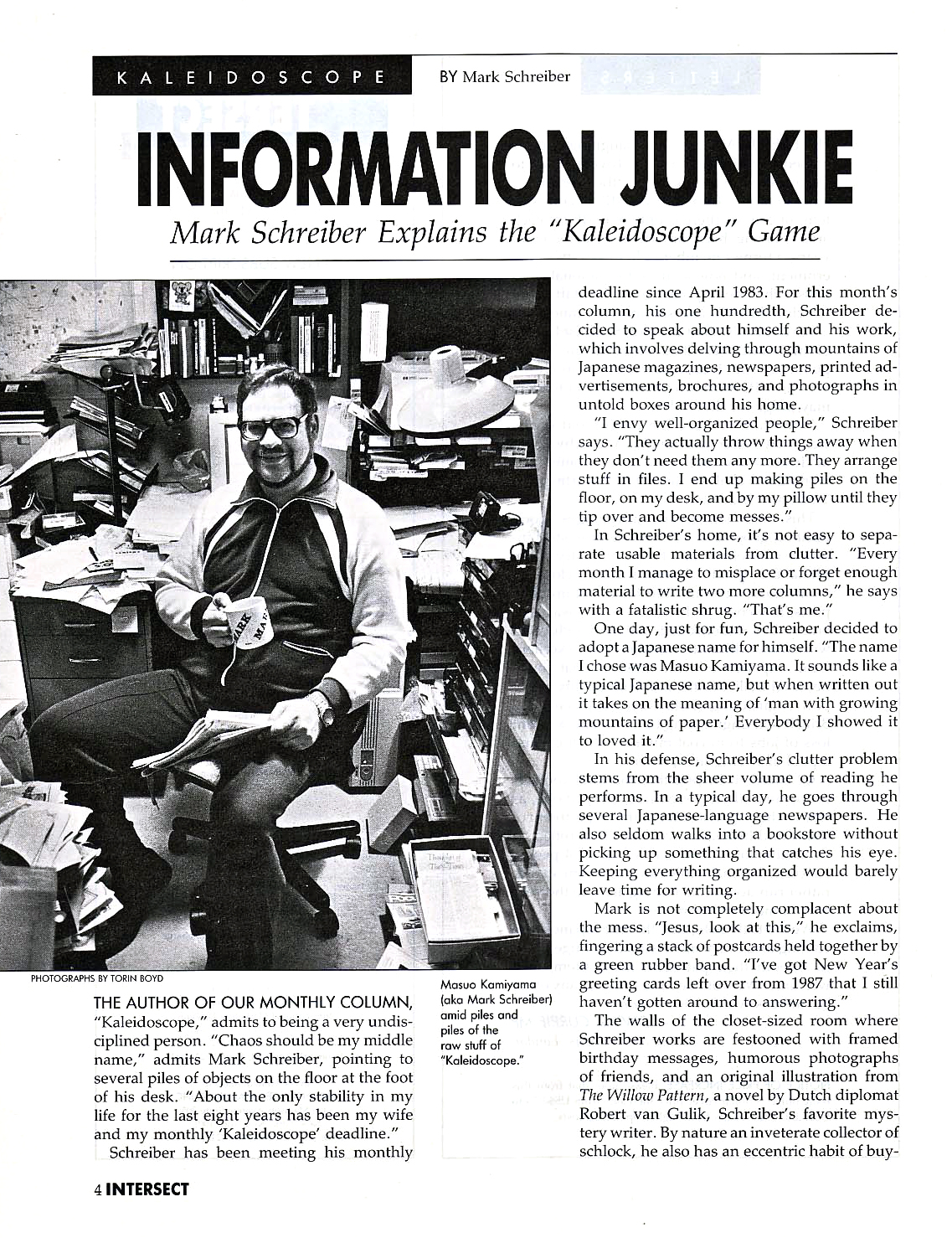

My Weekender story on the Capsule Inn Osaka, which appeared on Jan. 16, 1981, was given credit as a world "beat" and I was quoted by name in Newsweek, The Wall Street Journal, and several other publications. Through exposure of my Weekender articles I picked up a reputation as a gaijin who was familiar with the Japanese mass media. Mike Allen, co-editor of PHP, approached me about doing a monthly column for the English-language magazine published by the eponymous institute established in 1947 by electronics magnate Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of Panasonic. My "Kaleidoscope" column began from the April 1983 issue and ran for around 31 years.

Almost concurrent to acquiring my first computer in 1983, I had made tentative moves to becoming a columnist for magazines, and later newspapers. In spring of that year I'd purchased a Sanyo personal computer, running an operating system called CP/M, from Procom, a British-owned business startup in Kojimachi. Procom sold a system consisting of a Sanyo PC, a Diablo daisy wheel printer, and WordStar, which dominated the then nascent word processing software market, for just under 1 million yen.

WordStar changed my life. Within minutes I was doing something I'd never been able to do on a regular typewriter, which was to compose text on the fly. Prior to that I wrote out a draft in longhand and typed it in. Now I could compose at the keyboard, and not only hit the backspace to correct typos but also cut and paste, to move, or delete, blocks of text.

WordStar changed my life. Within minutes I was doing something I'd never been able to do on a regular typewriter, which was to compose text on the fly. Prior to that I wrote out a draft in longhand and typed it in. Now I could compose at the keyboard, and not only hit the backspace to correct typos but also cut and paste, to move, or delete, blocks of text.

Within a year I'd upgraded to my second Sanyo. The floppy disk formats of different PC manufacturers were almost all incompatible, so I would use a special utility that made the Sanyo-formatted 5" floppy disks readable on IBM PCs and some other machines. Another utility could be used to strip the WordStar encoding and convert the file into generic ASCII text, in theory readable by any computer. But these methods were imperfect and often glitches would occur, such as missing letters or garbled text.

Though I now had a PC at home, in the Aiwa office I still did my writing in longhand. I passed handwritten drafts to Yoshioka Kazuko, a skilled typist able to decipher my otherwise illegible scribble. She would generate a typewritten manuscript on the office's sole dedicated word processor, from which I could do further editing if needed.

Next, around 1985, I acquired my first home facsimile unit, a Canon. Initially the fax was on the same telephone line as my voice phone, and it wasn't equipped to switch automatically between one or the other. This meant if someone wanted to fax a document to me they phoned first and I would run upstairs and switch on the fax. This frustrating system lasted until I realized the price of a second phone line from NTT more than paid for itself with a single job.

Unfortunately, faxes in a small house had a down side: transmissions from overseas would often arrive in the wee hours. The fax's beeps and tweets, plus the shnipp-shnapp sounds of the paper cutter that it emitted in the middle of the night did not bother me, but invariably awakened the lady of the house

By 1996 I had settled into a separate office, which solved the disruptive fax problem.

I was slow in obtaining a modem and signing up for the internet. I am still something of a Luddite and don't use a mobile phone to this day. And I used my 300-baud-per-second acoustic modem only once, out of desperation. A typhoon was approaching and rain was falling in torrents, but an article was due for a PR magazine I wrote for. A young lady named Madoka, who was handling the account insisted I don my rain gear and battle the elements to carry a floppy disk with the data all the way to her Hamamatsu-cho office.

"Can't I try to send it to you via modem?" I asked. "Modem? What's that?" came the reply.

By fortunate circumstance, a friend named Nick happened to be working for a production company in the office building immediately adjacent to my client's. And he had a 300-baud acoustic modem.

About 10 minutes after my conversation with Madoka, Nick walked into her office and handed over a 5" floppy disc containing my text. "What's this?" she asked him. "It's the job from Mark Schreiber," he replied. According to Nick, her mandible made contact with the floor. I stayed dry that day, and she soon arranged for me to submit my future work over the phone lines.

I soon upgraded to a faster modem that could send and receive at 1,200 bps. It was a noisy device that issued a raucous series of clicking, gurgling, and howling noises as it "shook hands" with the party on the other end. Eventually, some years ago, I signed up for Tokyu Cable TV, which has a noiseless high-speed broadband connection, and for the past several years also came bundled with a home-use wi-fi.

My current computer is a Mac Mini with 16GB of RAM and a 1TB solid-state drive. It's connected to a 24" Eizo LCD monitor. I religiously back up my work and other archival data on an external 1TB HDD, while sitting atop a comfortable Herman Miller chair that has supported my 110-kilogram bulk for the past two decades without a complaint.

Over the years my printers went from daisy wheel to dot-matrix to laser printer. I now use one of Canon's combination A4 printer-copier-scanner models. These days I actually make use of the scanner much more frequently than the printer. I'm not yet quite at the stage of having a paperless office, but I'm getting there. My office floor, which doubles as a wastepaper bin, is another story.

For travel and work outside, I carry my MacBook Air purchased in early 2021. It's powered by Apple's new super-fast M1 CPU chip, and can be operated for about 18 hours on a full charge. The screen definition and colors are superb, allowing me to read e-books or view videos on it without eyestrain.

In terms of speed, power and reliability of my system, I'm content. I can't imagine needing any upgrades for the next three years, but you never know.