February 12, 2014

An Afternoon with Amy Chavez

By Ted Taylor

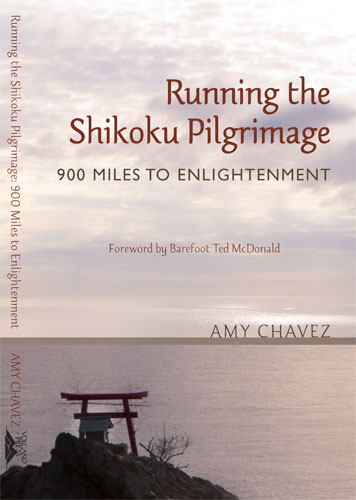

Amy Chavez spoke to SWET Kansai about her life as a writer and the challenges of the profession, especially with the publishing of her latest book, Running the Shikoku Pilgrimage: 900 Miles to Enlightenment. (See also Japan Funny Side Up.) Chavez came to Japan in 1993 on an exchange program to fulfill her requirements for an M.A. in Teaching English as a Second Language and worked for the next 10 years as a university teacher in the city of Okayama. In 1997, she started writing a column titled “Japan Lite” for the Japan Times, documenting traditional life on Shiraishi, a small island of just 900 people in the Seto Inland Sea. In 1998, Chavez ran the 88-temple Shikoku pilgrimage route, the journey that forms the subject of her current book. Her talk was held at the Hyogo-ken Shigaku Kaikan in Kobe on November 3, 2013.

- - -

“Writing is the best job you can have.” Amy Chavez quickly communicated her enthusiasm for writing to the group of 15 or so that had gathered for the SWET event on a rainy Sunday afternoon in Kobe. “Professional writing is the best job you can have,” she further elaborated, saying that, “As a professional writer, you have an audience that others don't have. Given a platform for your views, this gives you the opportunity to make a difference in people's lives.”

“Writing is the best job you can have.” Amy Chavez quickly communicated her enthusiasm for writing to the group of 15 or so that had gathered for the SWET event on a rainy Sunday afternoon in Kobe. “Professional writing is the best job you can have,” she further elaborated, saying that, “As a professional writer, you have an audience that others don't have. Given a platform for your views, this gives you the opportunity to make a difference in people's lives.”

The long-time Japan Times columnist feels that writing is a special job and that it is a privilege to have that job. We, her audience, were similarly privileged in hearing how this job came about, as it was the kind of personal journey that, in these days of uncertainty in the publishing world, may no longer be possible.

Chavez decided to pursue writing at age 13, when her sixth grade teacher encouraged her to submit her first magazine piece. She continued to write through university, receiving a B.A. in creative writing and a pair of M.A.s in technical writing and TESL. However, she eventually became convinced that she wouldn't be able to make a living by writing, and Chavez chose instead to pursue parallel interests in travel and in ESL teaching.

Taking what she thought to be the practical option, Chavez began teaching English in a Japanese university upon receiving her M.A. and was enjoying her career, only to find within four years that it was not to translate into the kind of security and solidity she had expected. The setback proved to be a gift in disguise, as it enabled her to reconsider her earlier attraction to writing. This process had actually begun while she was still teaching. She devoted the better part of a year to reading the work of various columnists and ultimately decided to become a humor writer.

Next, she examined various publications in order to see where she might best use these skills. She noticed that the Japan Times was rotating through a pool of writers for their humor section and thought to herself that what the publication needed was a single, consistent, and local voice.

Crafting a half dozen pieces, Chavez submitted them to the Japan Times managing editor, who rejected them. She then wrote six more columns and sent them in again, to the same editor. She followed up her submissions with phone calls, and after calling every week for six months, she was finally told that she had the column. While that may not be the orthodox way to get a job in the publishing world, in her particular case persistence certainly paid off.

For Chavez, writing continues to pay off after 16 years. While she initially sent in six columns at a time for her “Japan Lite” column, she now crafts them one-by-one, usually in the morning when she’s feeling most creative and before things arise to distract her. When I asked her whether she finds it difficult to produce fresh material for a humor column, she replied that she always finds something to write about. Most important is to write from the heart. Not everyone will find humor in all the jokes, but if enough people like it, then it works.

Chavez’s path to a writing career may not have been her most important journey. In 1998, discouraged by the loss of her university teaching position, Chavez sought solace by running the Shikoku 88-temple pilgrimage, completing its full 900 miles (1,450 kilometers) in 31 days. If followed in the traditional manner, the pilgrimage usually takes between 40 and 60 days, though most modern pilgrims choose to undertake the journey by motorized vehicle. The fourth and final prefecture, Sanuki (Kagawa), is referred to by pilgrims as “The Dojo of Enlightenment.” Chavez believes that in enlightenment there is freedom. Where you have freedom, you can do what you want.

By that time, Chavez realized that she didn’t need a teaching job. Without one she would have more time to write. Being a writer means being free to live life on one’s own terms. In her case, she has a vast backlog of writing and doesn’t face any tight deadlines, so she is free to do as she likes.

That freedom, Chavez conceded, is partly due to her circumstances. She had already made her home on the small rural island of Shiraishi (between Kagawa and Hiroshima prefectures), where she has a much lower cost of living than many of those who live in big cities. While she didn’t expect to make much money from writing, living in the countryside means she doesn’t spend much either.

Another gift of the pilgrimage Chavez described was that it showed her that, rather than simply change her working situation, she needed to change her perspective. What was more important than finding a new job was to stay optimistic and to be happy with what she had. She commented that in today’s world, publishing and otherwise, conditions seem to be getting worse, and, as she reflected, what we have today we may not have tomorrow. Most important, she said, is to have realistic expectations of oneself and what one can accomplish.

Another gift of the pilgrimage Chavez described was that it showed her that, rather than simply change her working situation, she needed to change her perspective. What was more important than finding a new job was to stay optimistic and to be happy with what she had. She commented that in today’s world, publishing and otherwise, conditions seem to be getting worse, and, as she reflected, what we have today we may not have tomorrow. Most important, she said, is to have realistic expectations of oneself and what one can accomplish.

Having a flexible mindset toward expectations became particularly important during the writing of Running the Shikoku Pilgrimage: 900 Miles to Enlightenment. She reported spending a year’s worth of eight-hour days writing her draft from diaries and recycled related excerpts from her Japan Times columns, but it took almost a decade to get the book into print. As a professional writer, she needed to make money, so she felt it important not to accept an unfavorable contract for the book. She rejected the first two offers that came. Even when the right publisher finally did approach her, her difficulties were not over. Most comical, perhaps to us listening to her story, was hearing how she found after one round of editorial revisions that the entire manuscript had been changed to the past tense. (When she questioned her editor about this, she was told, well the action in the book takes place in the past, so….) Yet Amy is equipped with the determination of a long-distance runner, and she pushed forward to see her book finally published in January 2013 by Volcano Press.

Amy Chavez’s energy and commitment to her profession was infectious that rainy autumn afternoon in Kobe. The dilemmas and difficulties she has faced over the years have not diminished her love of writing. I look forward to following her as she continues along the professional writer’s path, her running shoes carrying her steadily forward.

Originally written for the SWET website, February 11, 2014.

© Ted Taylor