Donald L. Philippi (1930–1993): Linguist-scholar, Activist, Musician, Translator

SWET honors the memory of Donald L. Philippi, who was an accomplished translator and man of many other unusual talents. Although he was not a member of SWET, he was a friend and fellow spirit, whose work and convictions paralleled those of us active mainly in Japan. This memorial article is excerpted from the obituary by Frederick Schodt, first published in Bulletin of the American Translators Association. The full article is available at Schodt’s website along with three lengthy interviews that he held with Philippi in mid-1984.

SWET honors the memory of Donald L. Philippi, who was an accomplished translator and man of many other unusual talents. Although he was not a member of SWET, he was a friend and fellow spirit, whose work and convictions paralleled those of us active mainly in Japan. This memorial article is excerpted from the obituary by Frederick Schodt, first published in Bulletin of the American Translators Association. The full article is available at Schodt’s website along with three lengthy interviews that he held with Philippi in mid-1984.

Donald L. Philippi died unexpectedly from complications of pneumonia at his home in San Francisco on January 26, 1993. He was sixty-three years old.

Don was born in Los Angeles on October 2, 1930. His father was an animator and art director for Walt Disney. From an early age both of his parents encouraged him to have an interest in other cultures, and he did. An extraordinarily gifted man, he led a rich, colorful, and complex life, during which he was known to different people in different roles. He once said that he was several persons in one body. He had at least four identities.

1. The linguist-scholar. Don spoke fluent Japanese, and without visiting the Soviet Union developed a near-native command of Russian. He could read and write Slovak, and he could read and understand German, Spanish and French, as well as several other languages.

Don began learning Japanese on his own as a child in the late 1930s in Los Angeles, and continued to do so during the war when it was regarded as an “enemy” language. After studying at the University of California, Los Angeles, he went to Japan in 1957 on a Fulbright scholarship, and stayed until 1970. He studied at Kokugakuin University, a Shinto university in Tokyo, and on his own. He became an expert not only in classical Japanese but in Ainu, the nearly extinct language of the indigenous people of Japan. He also studied the Altaic languages of Siberia, such as Turkic.

2. The political activist. Around 1967, Don was caught up in the social convulsions of the era. He became involved with the radical student movement in Japan, and was loosely affiliated with the Revolutionary Marxist group (Kakumaru). As an observer of the movement, he attempted to write its history. As a participant, he was arrested several times and spent several weeks in jail. He returned from Japan to the Bay Area thoroughly disillusioned with politics. As he once said, “If any of those sects had succeeded in taking power, it would have caused an incalculable tragedy . . . the people I respected in those days were madmen, and I was a bit crazy myself.”

3. The musician. Before leaving Los Angeles in 1957 Don studied shamisen and chikuzen biwa. In Japan he became expert at them. He studied under the biwa performer Tanaka Kyokurei.

In the late seventies, Don combined biwa and synthesizer music and began performing in the local music scene under the name of Slava Ranko. In 1981 he issued a record album titled Arctic Hysteria. Don’s album and music influenced the emerging punk rock and new wave scene in San Francisco.

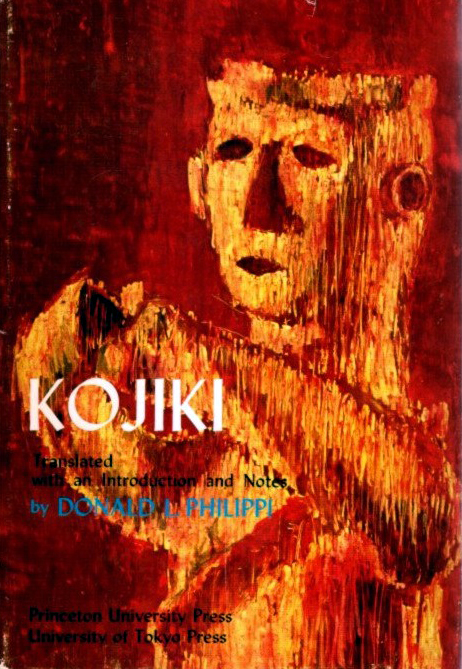

4. The translator. Don is best known as a literary translator. During his life he published at least four translations of ancient Japanese and Ainu texts. His translations of the Norito (ancient Japanese ritual prayers), the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), and a collection of Ainu poems titled Songs of Gods, Songs of Humans: The Epic Tradition of the Ainu, are widely regarded as classics. (The last two were published by the University of Tokyo Press.)

4. The translator. Don is best known as a literary translator. During his life he published at least four translations of ancient Japanese and Ainu texts. His translations of the Norito (ancient Japanese ritual prayers), the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), and a collection of Ainu poems titled Songs of Gods, Songs of Humans: The Epic Tradition of the Ainu, are widely regarded as classics. (The last two were published by the University of Tokyo Press.)

Don also had a career as a technical translator, and after 1961 largely supported himself doing technical translations. In 1983, he single-handedly began a crusade to increase the awareness of the importance of translating Japanese technical documents. With a newsletter titled Technical Japanese Translation, he inspired what became a movement among American translators, uniting them and giving them a cohesive voice, as well as a sense of pride. [The newsletter, neatly archived at Waseda University, is full of articles of great interest even in 2020.] In 1991 he played a central role in organizing the Second International Japanese-English Translation Conference. At the conference, his fellow translators presented him with a special award in recognition of his efforts.

In his more flamboyant moments, Don like to claim that translating technical documents gave him a “translator’s high”—that if he had a fast computer, and some post-modern archaic music by heavy-metal groups such as Motorhead to listen to, he could achieve a trance-like state. In reality, however, his true joy in translating technical documents probably came from the accomplishment of a more modest goal. He once said, “…by imposing a tiny bit of order in a communication you are translating, you are carving out a little bit of order in the universe. You will never succeed. Everything will fail and come to an end finally. But you have a chance to carve a little bit of order and maybe even beauty out of the raw materials that surround you everywhere, and I think there is no greater meaning in life.”

(Frederick Schodt)

Originally published in the SWET Newsletter, No. 53 (March 1993), p. 6, with thanks to Fred Schodt.

Comments:

There are no comments for this article yet.

Add your comment:

If you are a SWET member, log in to post a comment immediately. Comments are moderated for non-members.