Eileen Katō (1932–2008): Scholar, Translator, Editor

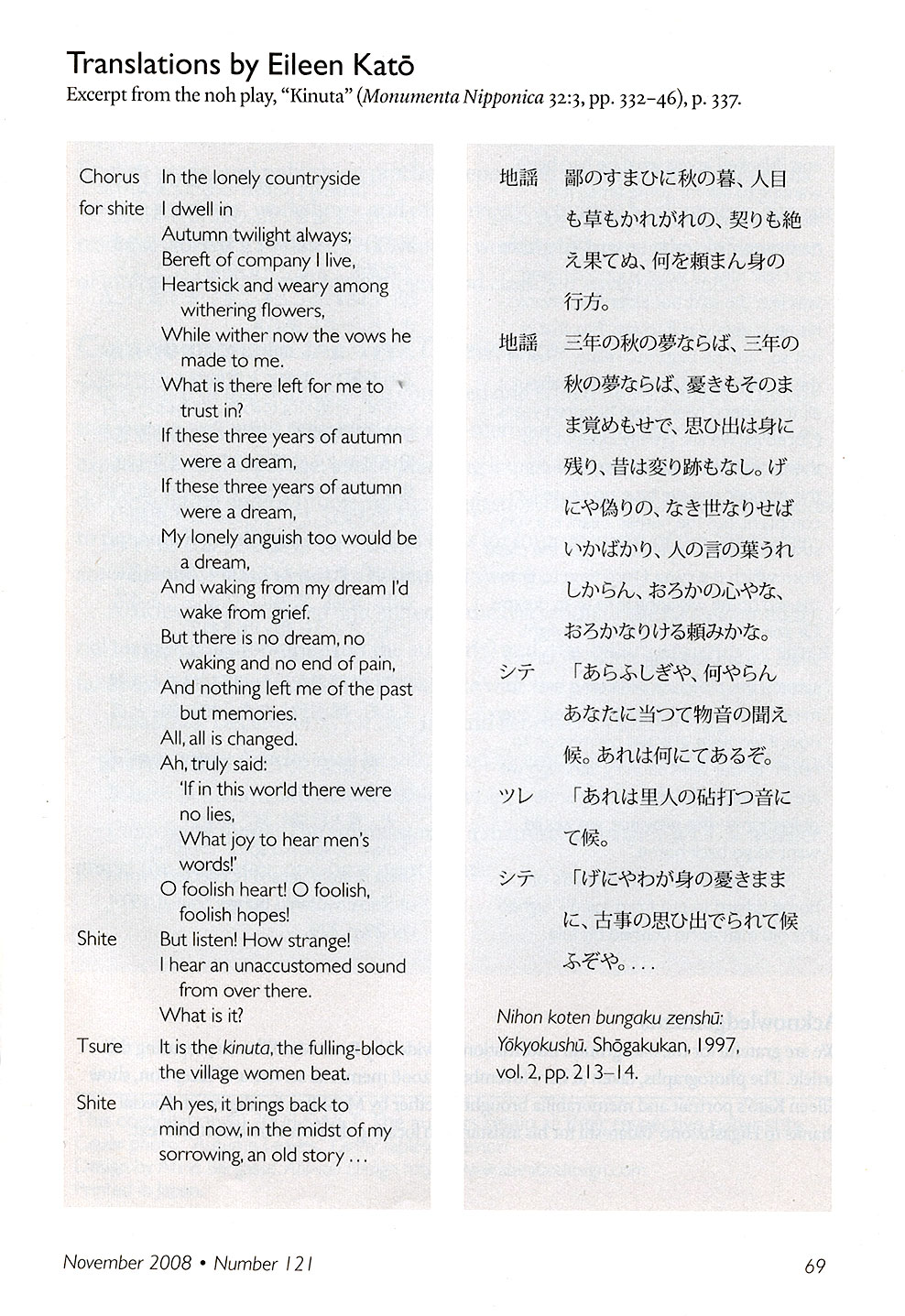

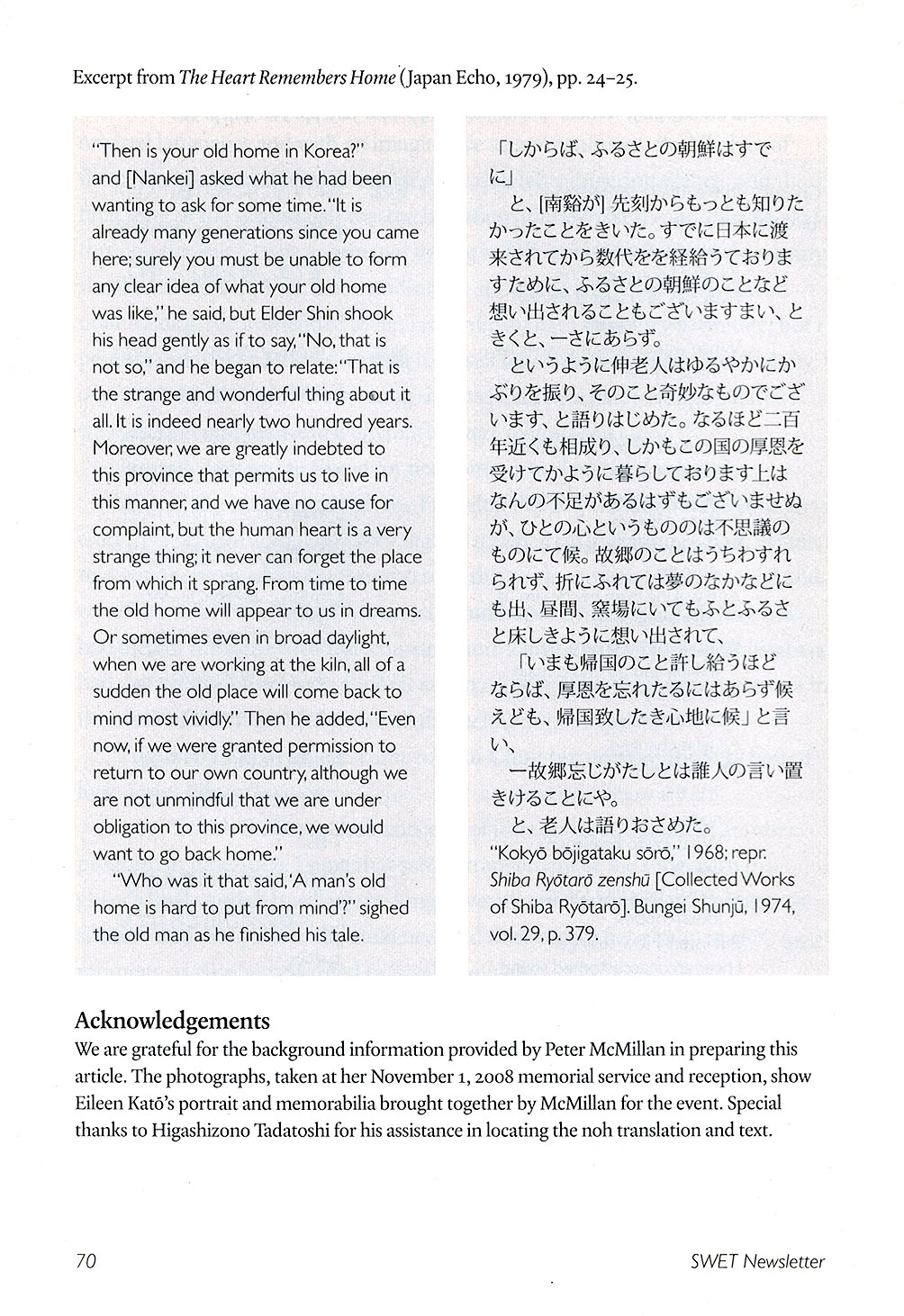

Ireland-born Eileen Katō (1932–2008) generously shared her poetic sensibility, deep erudition, and cosmopolitan experience in the cause of English wordsmithing in Japan. She translated noh plays and waka poetry, as well as two works by Shiba Ryōtarō; acted as an advisor in the Imperial Household Agency, and was a friend of many SWET members.

Over five decades, Eileen Katō quietly and elegantly contributed to a greater appreciation of Japanese culture. To mark her recent passing (August 30, 2008), we would like to set down something of who she was and get a glimpse of her legacy as a scholar of Japan and translator. She wrote, researched, edited, and translated, in the process helping countless authors transmit their messages in English, both privately and professionally. For 15 years, she held the post of goyōgakari in the Imperial Household Agency—a position with duties similar to those of an advisor—in which she translated the speeches, waka poetry, and other English writings of both the now-former emperor and empress. Katō’s published translations include some fiction by Shiba Ryōtarō, noh plays, and waka poetry (see examples below). She also translated waka poetry from Japanese into Gaelic, and old and modern Gaelic poetry into English.

Over five decades, Eileen Katō quietly and elegantly contributed to a greater appreciation of Japanese culture. To mark her recent passing (August 30, 2008), we would like to set down something of who she was and get a glimpse of her legacy as a scholar of Japan and translator. She wrote, researched, edited, and translated, in the process helping countless authors transmit their messages in English, both privately and professionally. For 15 years, she held the post of goyōgakari in the Imperial Household Agency—a position with duties similar to those of an advisor—in which she translated the speeches, waka poetry, and other English writings of both the now-former emperor and empress. Katō’s published translations include some fiction by Shiba Ryōtarō, noh plays, and waka poetry (see examples below). She also translated waka poetry from Japanese into Gaelic, and old and modern Gaelic poetry into English.

Born Eileen Lynn in the remote countryside of North Mayo, Ireland, in 1932, she specialized in French and Spanish at University College Galway and continued her studies in French, receiving an M.A. from the University of Poitiers in 1954. While pursuing further research at the Sorbonne in Paris 1954–56, she met Japanese diplomat Katō Yoshiya, and their marriage brought her to Japan in 1958. In accordance with foreign affairs ministry requirements at the time, she became a Japanese citizen and developed an abiding and deep knowledge of the country and language. She accompanied her husband on his assignments to New York (1960s), Paris (early 1970s), Beijing (1980–82), Cairo (1984–87), and Brussels (1987–90), and while in New York, earned a second M.A. degree at Columbia University.

In response to a request in 2004 to define a person of kyōyō (“cultivation”) in our own time, Katō wrote, “A person who is ‘cultivated’ is in tune with civilization at the point it has now reached, has had his/her character and intellect formed to be fully alive in this time of human history, is ‘educated’ in the original sense of having the best that is in him/her brought out (educare, meaning to ‘lead out of”), . . . and has wide-ranging and serious curiosity about countless things.” This definition perfectly fit Katō herself, and she was held in high esteem by scholars in Japan and overseas, leaders of high culture, and even members of the Japanese court.

Lynne E. Riggs

I first met Eileen Katō some time in the early 1990s, when an English professor of my acquaintance organized a small, informal group to discuss literature. The professor, though Japanese, spoke American English as her mother tongue and was accustomed to American social conventions. Not long after first meeting Eileen Katō, she ruefully told me that, when she had addressed her new acquaintance as “Eileen,” the other had bristled, making it clear that she was to be called “Mrs. Katō.” Being younger, male, and similarly antediluvian in outlook, I probably would not have made the same mistake, but I had the story in mind when, a year or so later, I addressed her as “Mrs. Kato.” She replied: “Oh, call me Eileen.”

I would like to think it no mere projection to remember Eileen—as I shall presume to call her now—as an esteemed senpai in what appears, at least for the moment, to be a distinctly old-fashioned Weltanschauung. Though worldly wise, she was not world-weary, and her fierce sense of justice and morality did not make her either judgmental or moralistic.

There were, to be sure, occasional displays of Irish indignation. When I once mentioned my distaste for a certain famous American political clan, she readily agreed and, drawing on her years as a diplomat’s wife, told me, her eyes flashing, of witnessing firsthand its Borgia-like behavior. She concluded with: “So, you see, I don’t care much for [them]!” (There was something in her elegant variety of Hibernian English that carried an air of authority.)

But Eileen could also be wonderfully magnanimous and forgiving, as I know from personal experience, having once committed a disastrously careless blunder that caused us both great embarrassment. Fully expecting excommunication, I abjectly apologized. She gave me a deserved scolding, but the next time I saw her (on the occasion of her brilliant lecture on Yeats and the noh given at the Asiatic Society of Japan), when I started once more to express my regret, she said: “Oh, enough of that, Charles! I’ve quite put it out of my mind, and you should too!”

One of the last times I saw her was at the memorial service of Father Neal Lawrence, with whom we had both served on the council of the Asiatic Society. As we filed out of the church, she came over to me and extracted a small book from her bag, shyly handing it to me. It was Jean Anouilh’s Antigone, which we had once briefly discussed. She had seen it in a French bookshop and thought of me.

Some years before, having naively supposed that I might still learn Gaelic properly, I presumed upon Eileen to help me understand a song: a dirge for the lost but glorious Jacobite cause. I gave her a cassette tape, not realizing what work I was imposing on her. A week or so later, I received a letter in the mail with a handwritten transcription and translation. Eileen was not only a fine linguist but a generous one to boot. Ar deis Dé go raibh a hanam.

Charles De Wolf

Well-known for her high-level literary translations, Eileen Katō might appear to have inhabited an exclusive literary sphere; but she was firmly grounded in the folk culture of her native Ireland, and some of my favorite memories of her are linked to this.

Well-known for her high-level literary translations, Eileen Katō might appear to have inhabited an exclusive literary sphere; but she was firmly grounded in the folk culture of her native Ireland, and some of my favorite memories of her are linked to this.

She was fairly recently widowed when someone brought her to an Asiatic Society meeting in the early 1990s, in the hope, I believe, of turning her thoughts for even a while from what was clearly a devastating loss. On the society’s council we got to know each other well, and at the May 2002 meeting she surprised me by handing over a paper bag with the words, “I got you a very Japanese ‘summer handbag’ for your birthday.” When I got it home, I discovered it was a beige and ecru lacy handbag—a Japanese summer gift indeed, and with a card inside that said, “Welcome to the club!” That was how I found out that we had been born less than ten weeks apart, and were now septuagenarians.

As a folk singer and bodhran player at “Irish” pub sessions two or three times a month, I was well aware of her deep, instinctive knowledge of the genre, dating from childhood, and when I was asked to conduct a 90-minute singing workshop at the Shamrock Festival in October 2005 I e-mailed her my tentative list of songs and asked for advice and additional suggestions. Eileen’s reply was to send me three of her own songbooks, each with little stickers marking the really good ones—“This was the name of a whorehouse frequented by sailors—a fine rollicking song” was one. Her note added that I might keep the biggest of the books but she would like the others back.

By chance it was at that time that the British Embassy choir had just started preliminary meetings to plan what would be its most ambitious project to date—the first staged version of the Howard Goodall CD recording of “We are the Burning Fire,” a collection of world folk and traditional songs, sung in the original languages and with an imaginative accompaniment. Both halves of the performance ended with a quiet piece that left a lingering silence, and the final song of the second half was the haunting (literally) Irish song “She Moved through the Fair.” I was nominated to sing it, folk style. One Irish friend, clearly shocked at the very idea that a non-native should be entrusted with such an undertaking, recommended several recordings that I might try to imitate; but I pointed out that I had been singing it myself for some forty years, and had my own style, which was to let the song sing itself and not let the singer get in the way of the young man and woman who were telling their story.

Naturally I turned to Eileen for her opinion, and received this reply:

“About ‘She Moved through the Fair,’ don’t let anyone discourage you. That is an Irish peasant song, only very slightly touched up by Padraig Colm. I think I told you the story of young Jim who sang this some months before he died and we all knew he was singing his own pain and hope to meet again his love who had died of the same dreadful ‘consumption’ a little earlier. None of us listeners had dry eyes! Your instincts about it are absolutely right. You just put yourself in the place of the singer and give it all the feeling you are capable of.

“I doubt if I will be able to come to your Choir but anyway, the very best of luck. Love, Eileen.”

In our British Embassy choir concerts of June 2006, and again in another program in June 2008, I sang that same arrangement of the song, with the ghost’s final words, “It will not be long, love, till our wedding day” fading into silence—and everyone in the audience held their breath for a long, magic moment, as if nobody wanted to break the spell.

I have very many affectionate memories of Eileen Katō over the past sixteen years, but perhaps this was the time at which two small feisty women with a passion for literature of all levels enjoyed being on entirely the same wavelength.

Doreen Simmons

(Originally published in the SWET Newsletter, No. 121, pp. 64–70.)

Comments:

There are no comments for this article yet.

Add your comment:

If you are a SWET member, log in to post a comment immediately. Comments are moderated for non-members.