Julia Nolet (1953–2024): Writer, Editor, Translator, Journalist, Friend

Julia Nolet was founder and owner of a small but respected translation company. But as Julia herself—a stickler for getting things right—might say, calling her a “translator” is like saying Tokyo Skytree is a tall building. Julia was a joyous, waving, chatty tower of attitude, as unfailingly compassionate to friends, family and even strangers in need, as she was unsparing when it came to pet peeves, which included official incompetence, social media, loyalty cards and lazy opinions about Japan. While wayfarers have come and gone, very few remained as perpetually, giddily, head-over-heels about calling this country their permanent home.

“I am so glad I live in Japan,” she wrote a friend, Martha Chaiklin, in 2020. “Perhaps one of the few good decisions I have made.”

In retrospect, “small business owner in Japan” is surely not a plot twist even Julia herself, a fan of adventure fiction, would ever have dreamed up. An early family photo from the 1950s shows a smiling crowd of well-dressed Nolets, her much-older siblings Leon, Leontine, Jean and Betty framing the background, with parents Napoleon and Bettie seated in front. The focus of the family portrait is Julia, a beaming child of about three, nestled front and center like a princess.

In retrospect, “small business owner in Japan” is surely not a plot twist even Julia herself, a fan of adventure fiction, would ever have dreamed up. An early family photo from the 1950s shows a smiling crowd of well-dressed Nolets, her much-older siblings Leon, Leontine, Jean and Betty framing the background, with parents Napoleon and Bettie seated in front. The focus of the family portrait is Julia, a beaming child of about three, nestled front and center like a princess.

A history provided by the family describes Nap as the taciturn owner of an electrical contracting business, who settled his family into an “enormous” house with postcard-views in Bellevue, WA.

“Julia was always up for adventure,” her younger brother, Martin, said in a tape-recorded reminiscence, describing lazy days exploring Lake Washington in a 12-foot aluminum boat from Sears. A typical horse-mad young girl, with equine figurines filling the shelves of her room, Julia was also an avid equestrian.

But her world was upended when Nap died suddenly after Christmas, 1962, a trauma that would permanently mark the year-end holidays as a time of grief.

Their mother quickly remarried to an electrician named Chester Nesheim. By the time Julia was in her teens, they were locked in perpetual combat over everything from her skirt length and antiwar opinions, to her habit of escaping, without a driver’s license, in the family station wagon. “She brought it back, with the fender all tore up,” Martin recalled. “It wasn’t a bad accident, but it sure made the car look ugly!”

By the time Julia was a high school senior, the family had decamped to an old house up a steep hill in Maui. She would acquire a succession of cars, zipping around the roads from Hana to Lahaina. Martin was amazed when Julia managed to defy gravity by getting a 1949 Lincoln up the steep driveway. It was soon replaced by a yellow Karmann Ghia with a Porsche engine, and a four-door Nova.

While the siblings shared a need for speed, Julia was the only one police seemed to pay attention to. “Julia even got a ticket for flipping the cop the bird,” he said. “I think they just liked to stop her because she was pretty!”

She worked at a pineapple cannery, attended community college, waited tables at a bar in Wailuku. Her main connection to Japanese culture, at this point, seemed to be buying Martin sashimi when he stopped by the bar after work.

But by 1978, she clearly was ready for a clean break. A legal notice in the Sept. 26 edition of the Hawaii Tribune Herald, just before her twenty-fifth birthday, reads “…the name of JULIA KATHRYN NESHEIM is hereby changed to JULIA KATHERINE NOLET.” Within a year, she was in Tokyo.

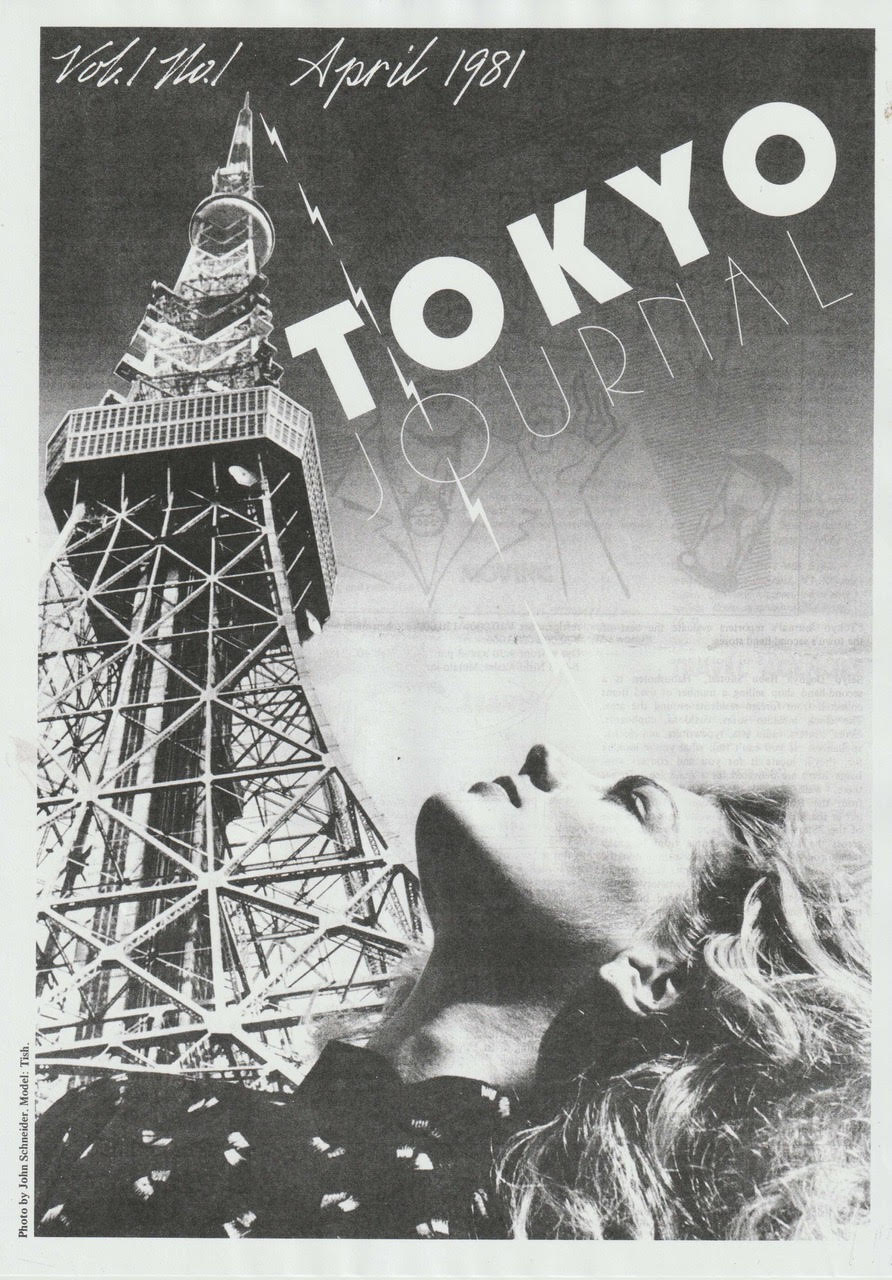

Working odd jobs while studying Japanese in Mejiro, Julia quickly hit the radar of another ambitious young woman, Naoko Tsunoi, who had managed to talk the language school’s owner into starting a new magazine. Getting Julia hired as staff writer for Tokyo Journal, as the hip entertainment monthly would be called, seemed the logical choice. “She was so slim and tall,” Naoko recalled. “So cool!”

Julia left an indelible impression on a Tokyo-based editor, Martha Debs: “After giving me a once-over, she told me with a big smile: ‘Martha, what you need are accessories,’” a single remark that would justify “decades of investment in scarves, bags, hats, belts, shoes and jewelry.”

Julia left an indelible impression on a Tokyo-based editor, Martha Debs: “After giving me a once-over, she told me with a big smile: ‘Martha, what you need are accessories,’” a single remark that would justify “decades of investment in scarves, bags, hats, belts, shoes and jewelry.”

Julia had an instinct for the art of the entrance, double-parking her white Mercedes in front of Ben Simmons’ photo exhibition and “hopping out of the car with all her bags, like a real shacho, ordered some prints, and immediately hit it off with the gallery director.”

By Tokyo Journal’s 1981 launch, Julia had kicked down the language barrier, comfortable in spoken Japanese. Despite a tiny budget and inexperienced staff, Julia was a dynamic presence in the office, and the publication quickly became required reading for the expat community.

“We were pretty amateurish at first, but I like to think that was part of the mag’s charm,” said Don Morton, who joined a few months later. “It was an honest amateurism. People trusted us.”

“We were pretty amateurish at first, but I like to think that was part of the mag’s charm,” said Don Morton, who joined a few months later. “It was an honest amateurism. People trusted us.”

The magazine’s office in Kamiyacho, above the old Magatani antique store, became her second home, former art director Koichi Hama recalled: “If not out in town selling ad space, (she) spent most days and many late nights there.”

Each month Don and Julia would jump in her ancient Toyota Corona Mark II to deliver thousands of copies across the city. “We all had fancy titles on the masthead,” Don recalled, “but Julia was in charge.”

Julia would go on to edit a small magazine, Far East Traveler, before joining Dentsu, the country’s top ad agency, as in-office translator. The arrangement didn’t last long.

“In her usual characteristic way, she said, ‘oh, I don’t want to come and work in your Japanese office,’” recalled Leanne Eames, one of Julia’s longtime contractors. Decades before the era of “remote work,” Julia was translating from home.

Assignments began to roll in from Dentsu as well as from a rival, Asatsu DK, and Julia set up her own translation company, Wordsworth, becoming an early tech adopter.

“She was the first person I ever knew who was using her phone handsfree,” Ben recalls. “Some in the group made fun of her (Bluetooth), but she was just ahead of her time.”

Julia’s Hawaiian roots showed in her penchant for “talking story,” her love of chitchat, with just about anyone she encountered. The quirk not only manifested a gregarious nature, but paved her road to language mastery outside the walls of academe. Her career would not have been possible had it not been for disciplined immersion in Japanese everyday life, including radio shows, NHK period dramas, and Japanese historical novels.

“Professionally, linguistically, she was a walking example of how much, in a good way, an autodidact can achieve,” friend Jimmy Nelson wrote. “I had the fancy degrees, Julia had the curiosity and the drive and the energy.

When the original Japanese-language marketing or advertising material was just too quirky, historical, vernacular or metaphorical for a more direct translation to ‘work’ commercially, Jimmy recalled, “she was able to massage her consumer translations into appealing, user-friendly language.”

Leanne marveled at Julia’s cajones when it came to standing behind her work, like the time a clueless client phoned in and kept insisting she had used the wrong word. “And she ended up saying, just go look it up yourself! And just hung up on him!”

But for those who were willing to listen, she patiently spelled out how and why a particular translation was rendered for maximum effectiveness in English. “It wasn’t translation,” Jimmy wrote. “It was translation-+.”

Julia’s lack of formal training led her to speak with a pronounced American accent, a trait fellow translators say was obviated by her unusual people skills. “She would talk to the bartender, she would talk to the waiter and they would all love her and remember her the next time,” said Martha Chaiklin, who joined Julia to translate a JTB Tokyo tourism guide in 1992.

When it came to expanding her knowledge, she was enviably unburdened by the fear of looking uninformed. “She would always ask questions about everything and anything,” Martha Chaiklin noted. “She had no shame in asking about something she didn’t know.”

Julia played as hard as she worked, quickly expanding her vast network of friends as she plumbed the hinterlands of her adopted homeland.

Athletic, with unusual reserves of energy, Julia herded gangs of foreign residents to slopes from Niseko to Togakushi as head of a local ski club, and golfed with a group of Japanese matrons dubbed her “obatarians.” To her friends, she became a kind of camp counselor, arranging trips to see the drummers of Sado and organizing picnics at fireworks festivals. When a client needed to unload unsold seats on a promotional tour, a bunch of us suddenly found ourselves in Greece.

“She was this just wonderful, amazing ball of energy,” said Debbie Howard, a longtime friend.

Julia could sniff out self-pity in a heartbeat and had little time for whiners. But for the truly distressed, she was a rock of Gibraltar, helping friends navigate paperwork, offering thoughtful advice or a tatami to crash on, guiding a lost motorist home over the phone, hosting ridiculously elaborate home-cooked dinners, and even babysitting my kids while I ran in a half-marathon.

“I was a giant pain in the ass,” said Martha Chaiklin, recalling how, during a traumatic divorce, Julia nevertheless stepped in to pack up and move out her belongings. “If you really needed help, she would be there for you.”

Describing Julia as “role model, close friend, and confidant,” niece Wendy Gough fondly recalled how her aunt “lectured me like a mom when she thought I was being dumb or going someplace she deemed nefarious.”

Buckner Nesheim was a rudderless college grad, when his aunt Julia “enthusiastically” offered free room and board. The time spent with Julia, he recalls, “was a huge influence on my life.”

The same could be said for all of us.

Julia died on Jan. 31, 2024, leaving behind her longtime partner, Toshio, many friends, and family.

Compiled by Lucy Craft, based on interviews with and remembrances by friends and family.

April 5, 2024

Photos:

Top: Gate of Julia’s “Ome Castle” home where she lived for many years until her death. (Photo courtesy of Ben Simmons)

Second: Julia (right) at an evening event. At left is her old friend Beth Reiber, author of many travel books about Asia. (Photo courtesy of Don Morton)

Third: Julia doing the cut-and-paste layout for Tokyo Journal. (Photo courtesy of Don Morton)

Fourth: Cover of the first issue of Tokyo Journal, 1981.

SWET invites memories of Julia Nolet to be added in the Comments section below.

Comments:

There are no comments for this article yet.

Add your comment:

If you are a SWET member, log in to post a comment immediately. Comments are moderated for non-members.