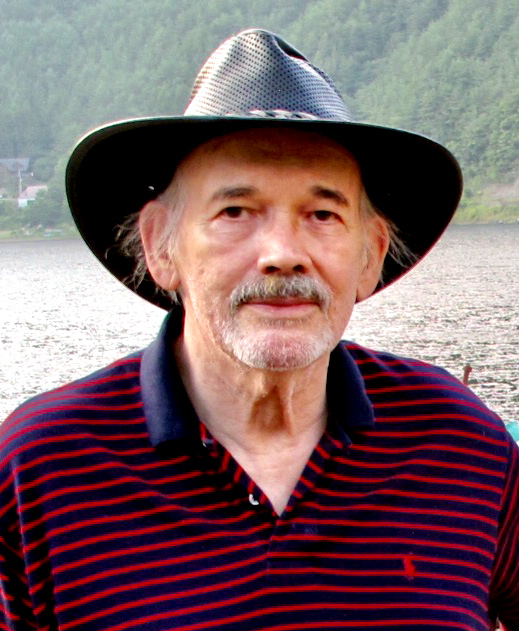

Michael Brase (1943–2021): Editor, Author, Publisher, Translator

Michael Brase, editor at Kodansha International from 1976 to 2003, and thereafter an independent editor, publisher, author, and translator, passed away on July 8, 2021. He was diagnosed with cancer a month earlier, and his health declined rapidly. His sudden loss came as a shock to his family, friends, and colleagues. The news reached SWET via his daughter, Mina Brase, of Yokohama, in early August.

Michael Brase, editor at Kodansha International from 1976 to 2003, and thereafter an independent editor, publisher, author, and translator, passed away on July 8, 2021. He was diagnosed with cancer a month earlier, and his health declined rapidly. His sudden loss came as a shock to his family, friends, and colleagues. The news reached SWET via his daughter, Mina Brase, of Yokohama, in early August.

Michael Brase was originally from Fresno, and grew up in California. He married a college sweetheart, and the couple came to Japan in 1964. Michael enrolled at Sophia University and completed his B.A. degree there. Part of what brought Brase to Japan was his determination not to be drafted to fight in the Vietnam War, and he eventually acquired Japanese citizenship.

Brase’s career as an editor began with work at the Charles E. Tuttle Company (founded 1948), then one of the leading publishers of books on Japan, where he remained from 1968 to 1974. Among his colleagues there was Susie Schmidt (later an editor at the University of Tokyo Press). His boss and mentor was chief editor and designer Florence Sakade, who taught him and many others the craft of editing. He also began to study Japanese. (“I started to study Japanese with Eleanor Jorden’s tapes while learning how to edit a book,” he wrote.)

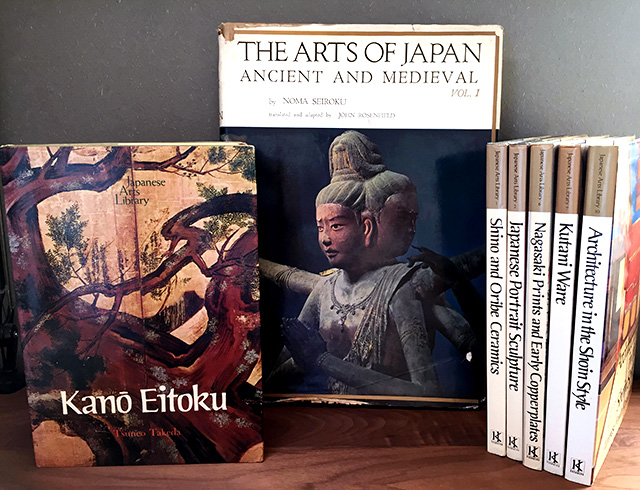

In 1976 Brase applied for a job at Kodansha International, which had become a dynamic publisher of high-quality books on Japanese art and culture, translations of fiction, and how-to books relating to Japan with its founding in 1963. “When I was interviewed by Kim Schuefftan and Nobuki Saburo for a job there,” he recalled, “they asked if I was interested in Japanese art, and although I said ‘Not especially,’ I found myself hired to work under Suzuki Takako on the Japanese Arts Library, which was just then starting up at KI, supervised by John Rosenfield at Harvard and translated by his graduate students.” The 15 books in the series that he worked on from 1977 to 1987 include the volumes Early Buddhist Architecture, Classic Buddhist Sculpture: The Tempyo Period, The Japanese Sword, Japanese Castles, and Esoteric Buddhist Painting.

Michael is remembered by colleagues who worked with him at Tuttle and Kodansha as modest, unassuming, hard-working, and professional, and as a real “man of words”—always interested in languages and their various forms and quirky characteristics. In his early working years at Tuttle, he made a practice of walking to the train station from the office each evening with a colleague from the business department who did not speak English, so that he could practice his Japanese. His dedication to raising Mina (who was very young at the time) to be bilingual extended to pretending not to understand Japanese so that his daughter would be forced to speak only English with him—a form of self-discipline that was admired by his colleagues.

Michael is remembered by colleagues who worked with him at Tuttle and Kodansha as modest, unassuming, hard-working, and professional, and as a real “man of words”—always interested in languages and their various forms and quirky characteristics. In his early working years at Tuttle, he made a practice of walking to the train station from the office each evening with a colleague from the business department who did not speak English, so that he could practice his Japanese. His dedication to raising Mina (who was very young at the time) to be bilingual extended to pretending not to understand Japanese so that his daughter would be forced to speak only English with him—a form of self-discipline that was admired by his colleagues.

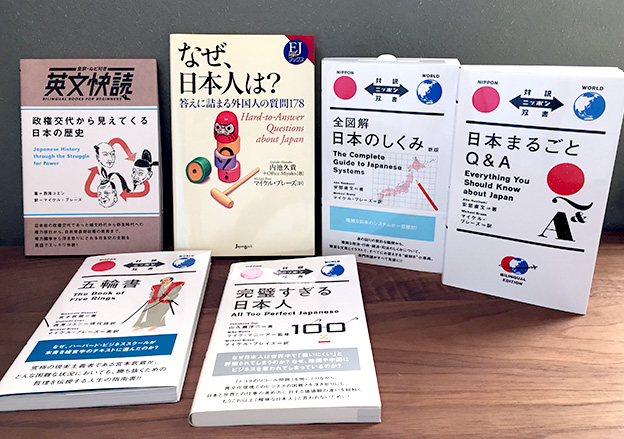

Michael’s passion for language developed further when he began to edit books for Japanese language learners. In an email to a SWET member in May 2021, he wrote: “I think one of my greatest accomplishments at KI was the Power Japanese series, which Shigeyoshi Suzuki and I started after I stopped working on the Japanese Arts Library. We were actually creating the books, not just translating them. . . . Looking back now, I can see that some of them were not that great, though at the time we thought we were doing something new. . . .One of the great things about Power Japanese was that we could initiate a project, find an author, produce an outline with the author, get the book accepted at KI, have the author create a manuscript, and make the book. It was in great contrast with the Japanese Arts Library, in which I got involved only when the manuscript was finished.”

Brase wrote that the most entertaining book in the series was Making Sense of Japanese, by Jay Rubin, who wrote so well that no editorial help was needed at all. “There is an interesting story about that book,” he said, “one chapter of which was called “Gone Fishin’’:

“Gone Fishin’” is the English equivalent of Honjitsu wa yasumasete itadakimasu. I liked this chapter title so much that I made it the title of the book. Warren Iwasa, in the sales department, disagreed, saying that it didn’t tell what the book was about. The book was published, and sold a few copies; then we learned that some bookstores were placing it with books on fishing and hunting. That’s when the title was changed to Making Sense of Japanese and started to sell, which made Warren happy. Rubin apparently later said, before gaining fame as a translator, that he got more fan letters for this book than any other.

Other books in the Power Japanese series included How to Sound Intelligent in Japanese, All about Particles, “Body” Language, and Read Real Japanese: All You Need to Enjoy Eight Contemporary Writers (authored by Janet Ashby and still selling well as a textbook).

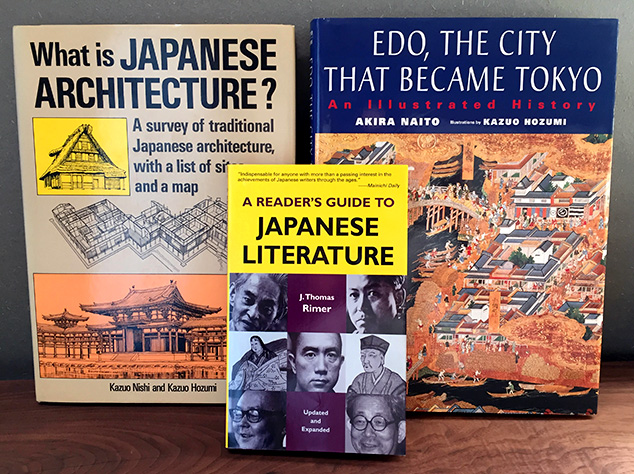

In correspondence Brase also revealed the motivation behind some of the books that he edited, “like persuading J. Thomas Rimer to write A Reader’s Guide to Japanese Literature (1989), the idea for which I took from Clifton Fadiman’s Lifetime Reading Plan. Also, having edited several books on architecture, but not really understanding the basics, I found a good introductory book and had it translated as What Is Japanese Architecture? I did something in the same vein for Edo, the City that Became Tokyo.” Other books he edited at KI included The Genius of Japanese Carpentry and two volumes in the Kodansha Japanese Biographies series, on Three Modern Novelists and Three Zen Masters.

In correspondence Brase also revealed the motivation behind some of the books that he edited, “like persuading J. Thomas Rimer to write A Reader’s Guide to Japanese Literature (1989), the idea for which I took from Clifton Fadiman’s Lifetime Reading Plan. Also, having edited several books on architecture, but not really understanding the basics, I found a good introductory book and had it translated as What Is Japanese Architecture? I did something in the same vein for Edo, the City that Became Tokyo.” Other books he edited at KI included The Genius of Japanese Carpentry and two volumes in the Kodansha Japanese Biographies series, on Three Modern Novelists and Three Zen Masters.

After retiring from KI, in 2004 Brase established his own Japan & Stuff Press. A reprint edition of Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: The Firsthand Experiences of a British Woman in Outback Japan in 1878 (2006) and Reading Japanese with a Smile: Nine Stories from a Japanese Weekly Magazine for Intermediate Learners (2007) were his first titles, and he then began a series called Classics Retold to Be Read, Not Just Revered, which included Thoreau’s Walden and Okakura Kakuzō’s The Book of Tea (2008). In 2010, Brase translated and also published The Manga Biography of Kenji Miyazawa by Ko Yano. This book was followed by Nitobe Inazō’s Bushido: The Soul of Japan (2011) and two Japanese language titles, Start Speaking Japanese Today (2011) and Switching Smoothly between Casual and Polite Japanese (2012).

Brase began taking on freelance translation work in 2005. Among his earliest translations were limited-vocabulary books for the IBC Publishing Company (a Tokyo-based publisher of educational and business books mainly aimed at the Japan market). These included rewrites of literary classics like Mori Ōgai’s Takasebune (2005) and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s Rashomon (2021), non-fiction like Coen Nishiumi’s The Honda Soichiro Story (2012), Shigeaki Hinohara’s Living Long, Living Good (2006), and The Gods of Japan (Taiyaku Nippon Sōsho) by Naobumi Abe. Brase was the author of two books published from IBC, Jeff Bezos’s Ambition (2014, IBC Bilingual Library) and Lost in Tokyo (2015, IBC Ladder Series).

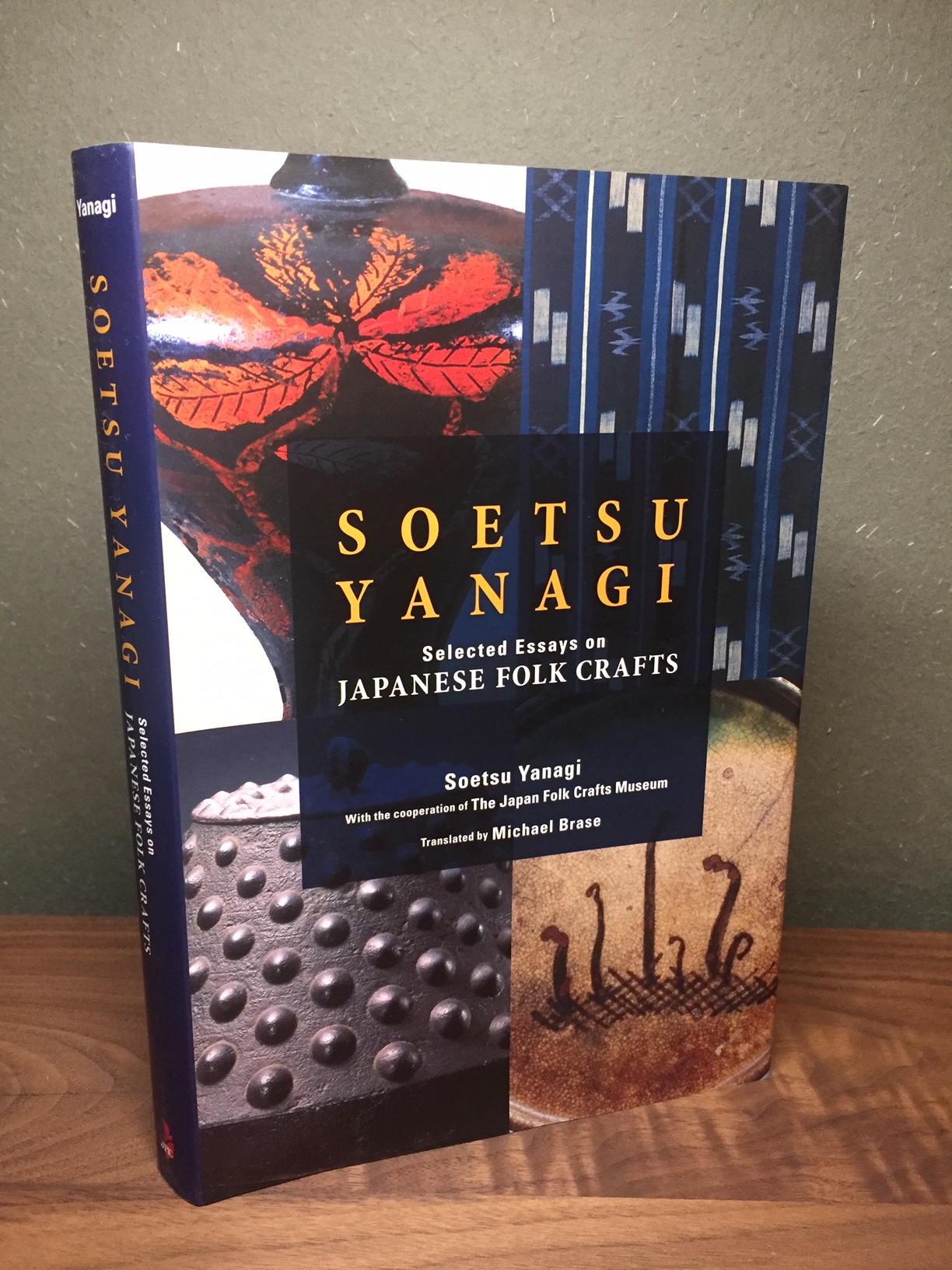

Then he translated “my first real books,” The Culture of Japan as a New Global Value by the conservative politician Shimomura Hakubun (2016) and Japanese Girl at the Siege of Changchun: How I Survived China’s Wartime Atrocity (2016), the autobiography of Homare Endō. He considered the latter title, published by Stone Bridge Press, his “magnum opus as a translator.” The steady trail of his translation output continued with titles published in the “Japan Library” series by the Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC), including Soetsu Yanagi: Selected Essays on Japanese Folk Crafts (2017), which won the 2018–2019 Lindsley and Masao Miyoshi Translation Prize awarded by the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture at Columbia University. His other titles from JPIC include The Building of Horyu-ji: The Technique and Wood that Made It Possible (2016) and The World of Ito Jakuchu: Classical Japanese Painter of All Things Great and Small in Nature (2020).

Then he translated “my first real books,” The Culture of Japan as a New Global Value by the conservative politician Shimomura Hakubun (2016) and Japanese Girl at the Siege of Changchun: How I Survived China’s Wartime Atrocity (2016), the autobiography of Homare Endō. He considered the latter title, published by Stone Bridge Press, his “magnum opus as a translator.” The steady trail of his translation output continued with titles published in the “Japan Library” series by the Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC), including Soetsu Yanagi: Selected Essays on Japanese Folk Crafts (2017), which won the 2018–2019 Lindsley and Masao Miyoshi Translation Prize awarded by the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture at Columbia University. His other titles from JPIC include The Building of Horyu-ji: The Technique and Wood that Made It Possible (2016) and The World of Ito Jakuchu: Classical Japanese Painter of All Things Great and Small in Nature (2020).

In 2015, Brase participated in SWET’s long-running Talk Shop series, giving a talk about his experiences and methods of translating to a small group meeting in Jinbocho. He continued to translate steadily until shortly before his death, with titles like The Kamala Harris Story and Say Hello to Saint-Exupery by Coen Nishiumi appearing from IBC Publishing in summer 2021.

Daughter Mina Brase wrote: “Throughout his career, he was attentive to the smallest detail and worked very hard in order to make sure the manuscript was of the highest quality, spending countless hours researching the subject matter at hand. His lifelong passion for his work remained unabated until the very end; just a week before he passed, I recall asking him about his recent editing project and his eyes lit up while he tried to explain the intricacies of the subject matter. Unfortunately, he had had a stroke at about the same time that he was diagnosed with cancer so was unable to speak in sentences, but during that conversation, he was able to piece together a sentence out of sheer willpower. He was a wonderful father and will be dearly missed.”

Mina also recalls that “my father also enjoyed translating poems by Miyazawa Kenji and short stories by Niimi Nankichi for pleasure as well as writing his own short stories. His favorite poem was Miyazawa Kenji’s ‘Ame ni mo makezu’ (Be Not Defeated by the Rain).” Surely a good motto for his life and work.

Compiled by Susie Schmidt and Lynne Riggs, with the cooperation of Mina Brase and Suzuki Shigeyoshi,

for the SWET website, October 4, 2021.

SWET invites readers to add their memories of Michael Brase. Please contact us at SWET.

Comments:

There are no comments for this article yet.

Add your comment:

If you are a SWET member, log in to post a comment immediately. Comments are moderated for non-members.