July 28, 2006

The Fan Quest for Authenticity

by Jessi Nuss, Meghan Strong, and Amanda Te

The fan translation done by fans of anime, manga, and video games for their own satisfaction and desire to share seeks to render the originals “authentically.” Trends and approaches from fan translation can influence “official” published translations and afford ideas for professional translators.

The word “translation” usually brings to mind the vast world of professional translation, where translators are paid for their work or do it as part of scholarly research or publishing. Another large area of translation, however, is emerging in which translation is done for free and for fun. This is “fan translation”—translation done by fans for fans. In most cases fan translations are done merely for the sake of other fans who seek to enjoy and understand something that is originally in a language that they do not know. Although there are clearly some problems with fan translation, such as mistakes and distortions, it has become so widespread that some publishers have started adopting certain styles and practices from the fan translation world for their “officially” published works. Here we will look at some of the differences between fan and official translations—that is, translations published by a company that holds the translation rights—and see what lessons there are to learn from this vibrant arena of the translation world.

Japanese-to-English fan translation is thought to have started with Japanese animation videos in the 1970s, when they slowly gained popularity among science-fiction and fantasy fans in the United States. Initially, most translations were typed onto paper, so viewers had to read the script while simultaneously watching the video in order to understand what was being said. As the practice became more widespread, however, fan translators began to subtitle videos on their own. These videos are commonly referred to as “fan-subs.” Fan translators began forming distribution groups, often creating websites where people could browse fan-subbed titles and place an order. However, even though fans were doing fan-subs for the fun of it and as a service to other fans, the process of obtaining the original video tape, translating, subtitling, and shipping out copies to fans was quite difficult and expensive.

In today’s digital age, the fan-subbing process has become a lot easier for both fan-subbers and fans. Nowadays, it is easy to copy shows directly from Japanese TV and convert them into a digital video file to be played on the computer. It still takes time to translate and subtitle the video file, but once that is done, the file can then be uploaded onto a website where fans from anywhere can download it, eliminating the costly need for obtaining and sending out video cassette tapes by mail. While in the past the most sought-out fan-subs were anime shows, lately fan-subs of dramas, variety shows, and even music shows are becoming popular. However, once an anime or manga becomes licensed for distribution outside Japan, it is common practice for fan translators to remove their fan translation from circulation.

In today’s digital age, the fan-subbing process has become a lot easier for both fan-subbers and fans. Nowadays, it is easy to copy shows directly from Japanese TV and convert them into a digital video file to be played on the computer. It still takes time to translate and subtitle the video file, but once that is done, the file can then be uploaded onto a website where fans from anywhere can download it, eliminating the costly need for obtaining and sending out video cassette tapes by mail. While in the past the most sought-out fan-subs were anime shows, lately fan-subs of dramas, variety shows, and even music shows are becoming popular. However, once an anime or manga becomes licensed for distribution outside Japan, it is common practice for fan translators to remove their fan translation from circulation.

How do fan translations differ from official translations? The truth is that there are quite a few differences—and it is from these differences that we may have something to learn. One clear difference regards the standard of the translations: while there are some talented fan translators who produce consistently high-quality work, they seem to be outnumbered by amateur fan translators with little experience or knowledge of Japanese. Anyone can do fan translation, and as a result, many enthusiastic fans will try their hand at translating their favorite anime/manga/show even though they have studied little Japanese—sometimes with dubious results. One example is one of the fan-translated versions of the anime Paradise Kiss, which was fan-subbed by two fans without a solid fluency in Japanese. As a result, the fan-subs contain mistakes that, while probably not noticeable to the average fan-sub viewer who does not understand Japanese, stand out to those who can follow spoken Japanese. One such error was mishearing the word Cinderella (pronounced “shin-de-re-ra”) as a form of the verb shinu, resulting in a translation that mentioned something about death, which was not only wrong but made no sense in the context.

Another major difference is the target audience, which affects certain translation practices. While professional translators of manga and anime are expected to appeal to both the mainstream market as well as the established fanbase, fan translators are concerned with one audience only: hardcore fans. They are not trying to sell a product—they only want to help fans like themselves understand and enjoy something that they love. Because of this, fan translators are able to take liberties and make certain assumptions that official translators cannot. Professional translators working for commercial publications are expected take into consideration an audience with little or no knowledge of Japanese culture, while fan translators can and do assume that their audience does understand certain aspects of Japanese culture or are willing to look up on the Internet things they don’t. Their translations usually try to stick as closely as possible to the Japanese original.

Another major difference is the target audience, which affects certain translation practices. While professional translators of manga and anime are expected to appeal to both the mainstream market as well as the established fanbase, fan translators are concerned with one audience only: hardcore fans. They are not trying to sell a product—they only want to help fans like themselves understand and enjoy something that they love. Because of this, fan translators are able to take liberties and make certain assumptions that official translators cannot. Professional translators working for commercial publications are expected take into consideration an audience with little or no knowledge of Japanese culture, while fan translators can and do assume that their audience does understand certain aspects of Japanese culture or are willing to look up on the Internet things they don’t. Their translations usually try to stick as closely as possible to the Japanese original.

This leads to the use of considerably more romanized Japanese words in the text than would usually be found in a mainstream translation. One example of this can be seen in Japanese terms of address such as -san, -chan, -kun, or -sama that cannot easily be translated into English. It is not uncommon for fan translators to leave these in, without any explanation, since most fans are already familiar with them. In the past, official translators simply omitted such titles, and if necessary changed the dialogue, as is the case with a scene from the manga Magic Knight Rayearth, which contained a conversation between several characters who were talking about the titles they should use to address each other. The terms are omitted, and the dialogue is rewritten so that it becomes a discussion of how the characters are close like sisters. However, recently there have been some cases—most notably in manga produced by Tokyo Pop—where the titles (in rōmaji) are left in with an added explanation as to their meaning and connotation, and this appears to be a practice copied from fan translators.

Another example of the differences between fan and professional translation is the handling of drawn-in sound effects, or onomatopoeia. In the early days of manga translating, professional translators would always translate these sound effects, which meant that the drawn-in Japanese text had to be erased and re-drawn in English, often with somewhat strange results. As an example, in the official translation of the manga Ranma 1/2, in a scene where the main character is fighting a panda, the sounds coming from a group of excited onlookers, originally written in Japanese as “zawa zawa hiso hiso,” were translated as specific remarks like “panda” and “big one” in the English version. While it is possible that the actual words spoken among the “chattering and whispering” of the onlookers included these words, they are not, strictly speaking, part of the original text. Considering that there are various onomatopoeia in English to express the talking and whispering of many people, it is a little puzzling that these words were not used instead. In fan translations, on the other hand, sound effects are always left untranslated and in the original Japanese characters. Some official translators such as those at Tokyo Pop have now started to follow this practice and leave onomatopoeia as is, providing a glossary at the back of the book as a reference. While some may say that doing this produces more “genuine” manga with the artwork and sound effects intact, others argue that it is bothersome to have to look up the meaning of sound effects, which often appear frequently and are meaningful to the progress of the story. Manga publisher Viz Comics continues to have English sound effects edited into the actual artwork, claiming that they offer “authentic manga with everything translated, including the sound effects.”

Another issue involves certain untranslatable terms closely connected to manga and anime like otaku and moe. Otaku and moe are examples of relatively fresh concepts of Japanese culture that have no English equivalents; otaku refers to someone who is a maniac about something (most commonly anime, manga, video games, and so on), often to the point of unhealthy obsession. Moe refers to the love for characters in manga and anime, especially those that are young and female. Moe is a somewhat obscure slang word specific to otaku culture, meaning that even most fans were probably not familiar with it before the appearance of a recent drama titled Densha Otoko (“Train Man”), which became very popular overseas after it was fan-subbed. The terms otaku and moe were left untranslated in the subtitles while explanatory subtitles were placed at the top of the screen. In most cases professional translators would not have the freedom to do this, and would have to come up with a solution that almost inevitably would change the meaning, inasmuch as these concepts are culture-specific and therefore difficult to translate accurately.

Other cultural concepts that can prove troublesome for translators include references to famous people. In some instances, these are changed to someone famous in the English-speaking world, for example in the manga Fushigi Yūgi (“Mysterious Play”) where a reference to Japanese pop star Amuro Namie is changed to American pop star Christina Aguilera. This, however, is anathema to fan translators—and to many fans themselves—and increasingly references to celebrities are kept as they would be in fan-subbed works. An example of this can be seen in the official translation of the manga Fruits Basket, where a character comments, “people say I look like Norika Fujiwara,” with a footnote at the bottom explaining that she is a Japanese actress, along with a link to her official website so that readers may see for themselves who she is.

Among the biggest challenges are visual puns and wordplay. Visual puns are especially difficult in that they rely on a visual to get the joke across, which means that the translator has to come up with something that will work in its place, otherwise the reader will not understand the point of the visual.

Fan translators have it easier because they can translate the pun literally and simply explain how it works in Japanese. Official translators, on the other hand, must come up with some kind of replacement in English, which can prove to be tricky. Frederik L. Schodt, translator of the famous manga series Astro Boy, handled one of the manga’s many visual puns very well by coming up with a solution that effectively related the meaning of the pun while also incorporating word-play in English. In one scene, some friends of Astro Boy are playing with a dog, telling it to “roll over” (“omawari” in the original). In the next panel, a policeman making rounds (or “omawari-san”) appears. Schodt solves this visual pun in the English translation by having the children say “Roll-over, puh-leeeez!” while the cop in the next panel says “You called for police?” turning it into a joke that works in English as well.

Fan translators have it easier because they can translate the pun literally and simply explain how it works in Japanese. Official translators, on the other hand, must come up with some kind of replacement in English, which can prove to be tricky. Frederik L. Schodt, translator of the famous manga series Astro Boy, handled one of the manga’s many visual puns very well by coming up with a solution that effectively related the meaning of the pun while also incorporating word-play in English. In one scene, some friends of Astro Boy are playing with a dog, telling it to “roll over” (“omawari” in the original). In the next panel, a policeman making rounds (or “omawari-san”) appears. Schodt solves this visual pun in the English translation by having the children say “Roll-over, puh-leeeez!” while the cop in the next panel says “You called for police?” turning it into a joke that works in English as well.

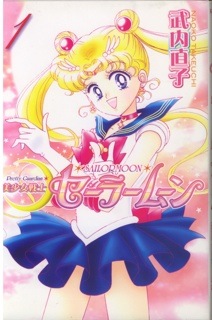

Puns don’t have to be visual to be hard to translate. The English translation of a pun that was a running joke in the Sailor Moon manga series caused quite a stir among fans who claimed that it was inaccurate. The pun involves the way the main character is teased by her friends about her hairstyle: in the original, her friends make fun of the way she ties her hair in two round buns by calling her “tankobu-atama” (lit., “lump-head”), while the main character insists that they look more like “dango,” or dumplings. The translator chose to translate these terms as “cow-tails” and “pig-tails,” respectively, reasoning that playing on “pig” vs. “cow” keeps the same humorous connection that the original displays by contrasting one blob (lump) with another (dumpling). Many fans did not agree, however, and insisted that a better translation for “tankobu-atama” would be something more along the lines of “meatball-head,” which would have remained consistent with the way it was translated in the anime series. As the number of readers who read English translations and are already familiar with the work grows, translators may have to be increasingly careful of how they choose to deal with such translation issues.

The translator chose to translate these terms as “cow-tails” and “pig-tails,” respectively, reasoning that playing on “pig” vs. “cow” keeps the same humorous connection that the original displays by contrasting one blob (lump) with another (dumpling). Many fans did not agree, however, and insisted that a better translation for “tankobu-atama” would be something more along the lines of “meatball-head,” which would have remained consistent with the way it was translated in the anime series. As the number of readers who read English translations and are already familiar with the work grows, translators may have to be increasingly careful of how they choose to deal with such translation issues.

In the end, the skills and rules that fan translators and professional translators appear to work by are quite different, due to the target audience for whom they are translating. However, recently official translators have been responding to the demand for close correspondence in translations from the growing number of knowledgeable anime and manga fans by adopting some practices commonly used in the fan translation world, such as leaving in the drawn-in sound effects, keeping Japanese titles of address and references to famous people, and so on. The challenge is finding a way to satisfy these fans while at the same time being careful not to alienate the average reader who may not be as knowledgeable about the work and about Japanese culture in general. It would be nice to see more published translations leave in Japanese cultural references and concepts so that the works can be not only entertaining, but can bring the reader closer to the culture and ethos from which the original comes. Japanese anime, manga, television shows, and so on can be a great gateway for learning about Japanese society and culture, and it would be gratifying to see more translations retaining certain cultural elements in order to better reveal the cultural richness of Japan.

TETSUWAN ATOM by Osamu Tezuka © 2002 by Tezuka Productions.

English translation rights arranged with Tezuka Productions. ASTRO BOY is a registered trademark of K.K. Tezuka Productions, Tokyo, Japan.

Unedited translation © 2002 by Frederik L. Schodt.

All other material © 2002 by Dark Horse Comics, Inc. All rights reserved.

Reproduced by kind permission of Tezuka Productions and Dark Horse Comics, Inc.

From the SWET Newsletter No. 112 (June 2006)